-

Preparing Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder for Adulthood A Transition Toolkit for Educators

UNIT 1: Transition Planning and Services for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)

Key Questions:

- What is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

- How are youth and young adults different than children with ASD?

- What are transition planning and services?

- Why are transition planning and services important for youth with ASD?

- What are the core components of transition planning and services?

- Are there special considerations in transition planning and services for youth with ASD?

- When should transition planning and services begin?

- How does the team determine transition goals and services?

- Are there special considerations in assessment for youth with ASD?

- Does my student with ASD need to be involved in his transition planning?

- What participation is needed by other agencies?

- How is person-centered planning related to transition planning?

- What is included in the transition IEP plan?

- Are more than academics needed in transition goals and services for youth with ASD?

- How can efforts towards a smooth transition be documented?

Appendices

- Appendix 1A: Online and Other Resources

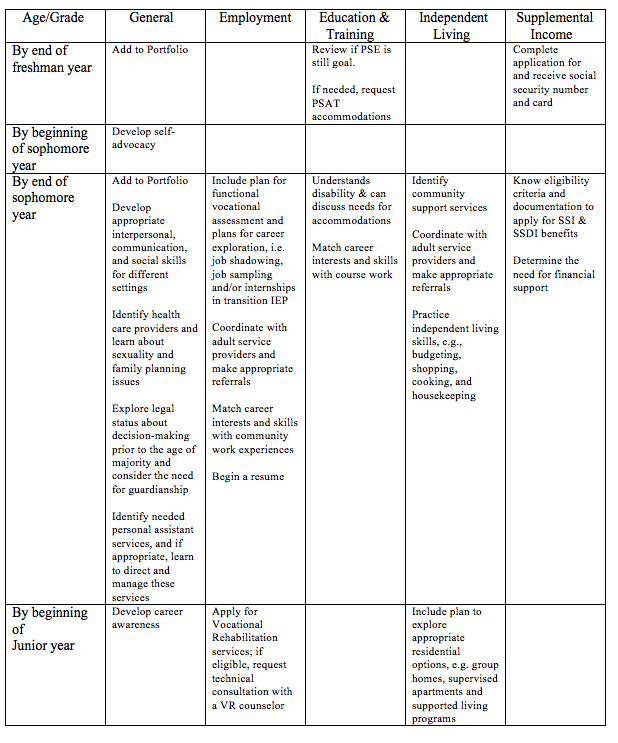

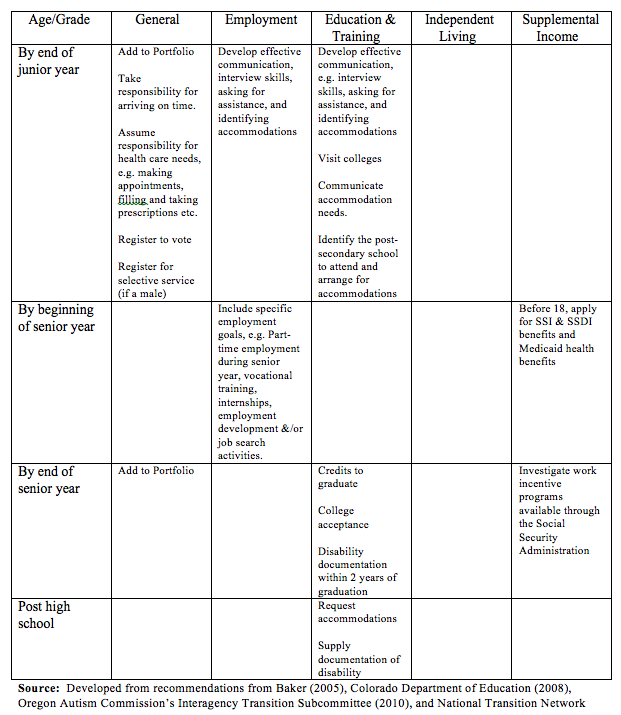

- Appendix 1B: Sample Transition Timelines

- Appendix 1C: Glossary of Terms

by Phyllis Coyne

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act (IDEA) in 2004 sought to improve adult outcomes for individuals with disabilities by requiring public high schools to provide better transition planning. Yet, educators, adult service providers and parents often do not fully understand the ongoing process for planning and providing transition services based on individual student needs. When partial knowledge about transition is combined with incomplete understanding of youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), these youth are unlikely to meet their potential for a satisfying adult life.

In order to assist Transition IEP teams to develop a comprehensive and individualized transition process, this unit provides basic answers to commonly asked questions and links to comprehensive resources about different aspects of transition planning. In addition, this unit offers basic information and links to resources on how to meet the unique needs of youth and young adults with ASD in transition planning and services.

Transition planning and services is a huge topic. Youth with ASD is an equally large topic. Since this unit it chock full of information and tools, it is recommended that you do not try to read it from beginning to end. It is a resource for you and is designed so that you can return to sections of the unit, as you need more information or tools. Feel free to print this unit for ease of reading or as an accessible reference. Links to questions, appendices and online resources are provided so that you can go directly to what is most relevant to you at the time.

What is Autism Spectrum Disorder?

ASD is a neurological, pervasive developmental disability that varies greatly in how it manifests. In order to be effective in preparing students with ASD for adulthood, educators must understand ASD. Educators cannot assume that that they understand a person with ASD just on the basis of the diagnosis or having had a student with ASD previously. Two students with ASD can act very differently from one another and have varying skills.

The broader term “Autism Spectrum Disorder” (ASD) is being used increasingly rather than “autism” in the literature, by professional organizations, by the medical community and by state departments of education.

Although ASD can range from very mild to severe, the overwhelming majority of individuals with ASD have milder forms of ASD. VanBergeijk and Shtayermann (2005) reported that the number of children with Asperger Syndrome is double the number of children with classic autism.

Under IDEA 2004 and under the Oregon Administrative Rules (Oregon Department of Education, 2006), “Autism” means a developmental disability significantly affecting verbal and nonverbal communication and social interaction that adversely affects a child's educational performance. Other characteristics that may be associated with autism are engagement in repetitive activities and stereotyped movements, resistance to environmental change or change in daily routines, and unusual responses to sensory experiences.

More specifically, to meet the eligibility criteria for special education services under autism/ASD in Oregon, a student must exhibit characteristics in the 4 defining areas of autism/ASD: 1) impairment in communication. 2) impairment in social interaction, 3) restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities, and 4) unusual response to sensory information. The Autism Spectrum Disorder: Evaluation, Eligibility, and Goal Development (Birth-21) Technical Assistance Paper (TAP) (2010) provides a thorough explanation of Oregon’s process to determine eligibility for special education services under the category of autism/ASD. 2016 note: the TAP is in the process of being updated.

Characteristics

No one behavior defines ASD. Although ASD is defined by a certain set of behaviors, youth with ASD can exhibit any combination of the behaviors in any degree of severity. “It is the combination or pattern of behavior and their intensity and the persistence of the behavior that is significantly beyond normal development that are associated with ASD” (Oregon Department of Education, 2010). The list below provides a brief description of some characteristics of ASD from the Oregon Department of Education (2010).

Impairment in communication. Can range from no verbal communicate/language to more subtle difficulties with the flow of the conversation and social communication (pragmatic language).

Impairment in social interaction. May include difficulties initiating or responding to conversation, difficulties using or responding to nonverbal gestures, lack of or inconsistent eye contact, impairments in responding to others’ feelings, challenges reading social cues and the context, difficulties working cooperatively with peers, and subsequent failure to develop peer relationships.

Restricted repetitive and stereotyped patterns of behavior, interests, and activities. Characterized by a strong preference for sameness and repetition with regards to interests, daily routine, and body movements that can manifest as limited range of activities and interests.

Unusual response to sensory information. May include over and/or under reaction to sounds, taste, pain, light, color, touch, temperature, and/or smells; seeking and/or avoiding activities that provide touch, pressure, and movement.

In addition, individuals with ASD have a specific profile of cognitive strengths and weaknesses. For instance, executive function is a core cognitive deficit of ASD (Adreon & Durocher, 2007; Frith, 1989; Hughes et al., 1994; Ozonoff, 1995; & Ozonoff & Griffith, 2000). Problems with attention control and attention shifting, planning and goal setting, flexibility, organization, time management, memory, self-regulation and metacognition have consistently been described as traits of individuals with ASD (Filler & Rosenshein, 2008; Ozonoff, 1998; Ozonoff & Griffith, 2000, Pennington & Ozonoff, 1996).

Strengths

Some of the characteristics of ASD may also be strengths for students with ASD. Although not everyone with ASD demonstrates the savant abilities of “Rainman” or Temple Grandin, individuals with ASD will have abilities that can be utilized in training/education, employment, independent living and community participation. Some of these include:

Systemizing. Individuals with ASD show proficient and sometimes even superior skills in “systemizing” (Baron-Cohen, 2003)). Systemizing is the drive to analyze or build systems in order to understand and predict the system’s behavior and its underlying rules and regularities. Skill in systemizing lends itself to the use of systems-oriented visual technologies, science, geography, electronics, music, and how things work, in general.

Specific interests. Their focus on specific areas of interest may allow youth with ASD to develop a unique perspective, a specific skill, or a depth of understanding, which lead to meaningful leisure activities and employment outcomes.

Hyperattention to detail. Hyperattention to detail often results in the youth being exacting and precise, which is useful for many jobs and other adult activities.

Preference for sameness. Due to the desire for predictability and routine, youth and young adults with ASD often have a tolerance for repetitive activities in employment and leisure.

Concentration. Youth and young adults with ASD can often attend to activities and tasks of interest for prolonged periods of time.

Long term memory. Many youth and young adults with ASD have a strong, detailed memory of what they have seen in the past.

Accuracy in visual perception. They may be able to replicate exactly from a model.

By necessity, the above section on ASD is brief. In order to provide you with more substantial information, Appendix 1A: Online and Other Resources includes links to many detailed sites about ASD. Two chapters from Higher Functioning Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism, Who Are Higher Functioning Young Adults with Autism? and Adolescence and Adulthood supply more information.

How are youth and young adults different than children with ASD?

Although ASD is a lifelong disability, considerably less is known about its manifestation in youth and young adults, but we know that there is a great variance in development. Some youth with ASD improve markedly, others experience deterioration in functioning (e.g. increased aggression, increasingly rigid or repetitive behavior, loss of skills), and many continue to progress over time in skills and abilities (Shea & Mesibov, 2005).

Seltzer et. al. (2003) found that the majority of adolescents and adults with ASD demonstrate a general pattern of lessening of symptoms with improved overall language, improved ability to communicate nonverbally, and reduced stereotyped, repetitive, or idiosyncratic speech. The specific manifestation of characteristics of ASD may change as children grow older, but continue into and through adult life with a broadly similar and often subtler pattern of persistent problems in socialization, communication, interest patterns, sensory reactions, and organization (Piven, Harper, Palmer & Arndt, 1996; Seltzer et. al., 2003; Sperry, 2001; Venter, Lord & Schopler, 1992). For instance, a youth who covered his ears or screamed when there was loud noise as child, may have learned how to cope with the noise in a variety of ways, so that there is no observable behavior that signals discomfort. However, that does not mean that he still does not have sensitivity to sound.

It is essential to recognize that improvement does not mean that youth with ASD do not continue to have challenges in a variety of areas. For instance, Wagner, Cameto, Garza, & Levine (2005) found that large numbers of youth with ASD rated low on self-care tasks, functional cognitive skills, social skills, and communication skills when compared with the entire population of youth with disabilities served under IDEA 2004.

Characteristics of ASD may become subtler or more functional over the life course, but it does not indicate that individuals with ASD do not need services and supports as they move through adolescence into adulthood any less than they did in childhood. Because of the ongoing need, Unit 2: Supports provides information and resources on the types of supports needed. Unit 3: Expanded Core Curriculum and the eight subunits of Unit 3 are designed to provide you with knowledge and methods to prepare youth with ASD for a meaningful adulthood.

Challenges Associated with Adolescence

Adolescence can be a particularly challenging time for some individuals with ASD and some behavioral features may become exacerbated. Gilchrest et al. (2001) reported that many had more problems in adolescence than in early childhood. The exact numbers of those who have more problems is not known. Nordin and Gillberg (1998) suggested that 12% to 26% of adolescents show cognitive or behavioral deterioration, while Ballaban-Gil et al. (1996) found that families reported that behaviors had worsened for 44% of adolescents. Even when the frequency of challenging behaviors decreases, any challenging behavior that does occur is often more distressing or dangerous, due to the increase in height, weight and strength from childhood to adolescence (Gillberg, 1991; Harris, Glasberg, & Delmonico, 1998; Nordin & Gillberg, 1998).

There can be a rise during adolescence in psychiatric symptoms. Bryson and Smith (1998) found that 40% of 14 to 20 year olds with ASD experienced psychiatric episodes, especially mood disorders with depression being the most common. Some studies have also found a significant increase in anxiety (Gillberg & Steffenberg,1987; Mesibov & Handlan, 1997).

Puberty is associated with the onset of seizures, especially complex partial seizures (Howlin, 2000). Reports of epilepsy vary but generally indicate a rate of 20% to 33% ( Bryson & Smith, 1998; Nordin & Gillberg, 1998). The development of seizures in adolescence is most frequent for individuals with ASD who also have an intellectual disability or marked developmental regression.

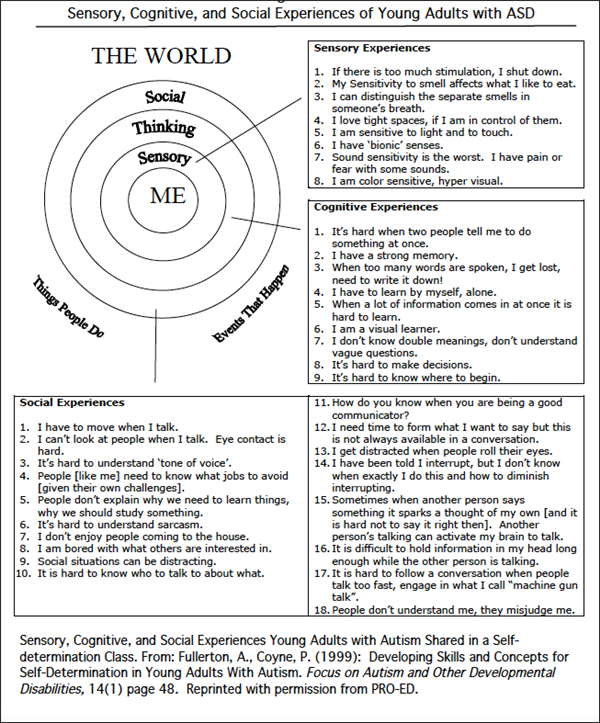

Personal Accounts from Youth and Young Adults

The behavioral features associated with ASD can vary considerably between individual youth and young adults with ASD. To provide you with a fuller picture of ASD in youth and young adults, links to video self descriptions are included in in Appendix 1A. Adolescence and Adulthood provides additional information on ASD in youth.

The following figure describes the experience of some higher functioning adolescents and young adults in their own words (Fullerton & Coyne, 1999).

What are transition planning and services?

Transition planning is a process designed to plan for life after school services end, through identifying dreams, goals, instructional needs and supports, and resources. It’s a logical, ongoing process that starts with the student and family’s vision for the future (which may change several times while the student is in school) and moves toward that vision. The transition planning process should guide the development of the IEP so that the focus remains on the dreams, preferences, and strengths of the student.

Transition services are intended to prepare students to move from school to adult life. IDEA 2004 (§300.43) defines transition services as follows.

(a) Transition services means a coordinated set of activities for a child with a disability that

(1) Is designed to be within a results-oriented process, that is focused on improving the academic and functional achievement of the child with a disability to facilitate the child’s movement from school to post-school activities, including postsecondary education, vocational education, integrated employment (including supported employment), continuing and adult education, adult services, independent living, or community participation;

(2) Is based on the individual child’s needs, taking into account the child’s strengths, preferences, and interests; and includes:

(i) Instruction;

(ii) Related services;

(iii) Community experiences;

(iv) The development of employment and other post-school adult living objectives; and

(v) If appropriate, acquisition of daily living skills and provision of a functional vocational evaluation.

(b) Transition services for children with disabilities may be special education, if provided as specially designed instruction, or a related service, if required to assist a child with a disability to benefit from special education.

One outcome of these transition requirements has been to focus attention on how the student’s educational program can be planned to help achieve his goals for life after secondary school. This includes having a high school experience that focuses on developing the skills and competencies needed to achieve life goals. It also involves helping the student identify and link with any post-school adult service programs or supports they may need to promote the student’s successful transition from school services to young adulthood.

Why are transition planning and services important for youth with ASD?

The number of young people who are receiving special education services under Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) in U. S. schools has increased to over 211,600 (NINDS, 2008). These children will mature into young adults, who may desire college, work, community participation, and independent living. However, The characteristics associated with ASD provide significant challenges in actualizing these dreams for both the majority of those with ASD and those supporting them.

It is generally accepted that an education for all children in the U.S. is designed to maximize their capacities for adulthood. Schools have little more than 12 plus years of preparation of students for 40 – 60 years of life in the community as an adult. Therefore, the stakes are high.

For youth with ASD, planning for adulthood is all the more critical (Gerhardt & Holmes, 2005). Without effective preparation for adulthood, young people with ASD experience less success in adult life than others with disabilities (Cameto, Levine, & Wagner, 2004). In fact, recent research reveals generally poor outcomes for young adults with ASD in postsecondary education, community living, and employment (Barnhill, 2007; Billstedt, Gillberg & Gillberg, 2005; Cameto et al., 2004; Cederlund, Hgberg Billstedt, Gillberg, & Gillberg, 2008; Howlin, Goode, Hutton, & Rutter, 2004; Jennes-Coussens, Magill-Evans & Koning, 2006; Schall et al., 2006).

Transition planning and services are an important foundation for ensuring a successful transition to work for all students, but especially for students with ASD. Since the early 1990s researchers have documented the importance of effective transition planning if students are to have positive post school outcomes (Handley-Maxwell, Whitney-Thomas, Pogoloff, 1995; Irvin, Thorin, & Singer, 1993). It is beneficial for all students with ASD regardless of the extent or type of ASD.

Youth with ASD require specialized support and planning throughout their transition from school to adult life. Due to the varied needs of individuals with ASD, there is no one size fits all. Thoughtful transition planning is needed whether the student is continuing on to college or is seeking employment with supports through a community provider or vocational rehabilitation agency.

What are the core components of transition planning and services?

IDEA 2004 has specific requirements for transition planning and services. The following provides a brief overview of the required components.

- Invitation and Participation in the IEP meeting. Invitations must be made to:

- The student and if he does not attend the IEP meeting, the school must take other steps to ensure that his strength’s preferences and interests are considered.

- With consent of parent(s) or a student who has reached the age of majority, representative of any participating agency who is likely to be responsible for providing or paying for transition services.

- Parent with a notice that indicates that a purpose of the meeting will be the consideration of the postsecondary goals and transition services of the student.

- Measurable postsecondary goals. Postsecondary goals must be:

- Appropriate and measurable

- Based on age appropriate transition assessment

- Include training/education, employment, independent living skills, where appropriate

- Extensive information on measurable postsecondary goals can be found through the links in Appendix 1A, such as Transition Goals in the IEP.

- Present Level of Academic Achievement and Functional Performance Present Level of Academic Achievement and Functional Performance includes:

- Student’s post school vision in employment, vocational training or higher education, and independent living

- Strength of the student

- Concerns of the parents

- Present levels of academic performance

- Present level of developmental and functional performance

- How student’s disability affects involvement in the general education curriculum

- Student’s preferences, needs, interests, and the results of the age-appropriate transition assessments.

Transition Services

Transition Services includes all of the major transition activities required to help the student connect and coordinate supports with adult services agencies, as well as identify what the student will learn and do both this year and in the remaining years in school to achieve his or her dreams and goals for the future. This includes:

- Identification of the supports and services the student needs for success

- Identification of the student’s course(s) of study

- Identification of instruction in academic, vocational and daily living skills

- Identification of needed related services

- Identification of community experiences and skills related to future goals

- Identification of process to explore adult service organizations and agencies to provide services and support, as well as necessary funding

The coordinated set of activities relies heavily on services and people both within and outside the school setting. Extensive information on transition services can be found through the links in Appendix 1A, such as Transition Services.

Annual IEP Goals

Annual IEP goals are measurable goals that reasonably enable the youth to meet the postsecondary goal(s) or make progress toward meeting the goal(s). Annual IEP goals to support post-school activities can be written within the general curriculum (a math goal), or outside of the general curriculum, such as transportation skills training. A given IEP goal may support more than one postsecondary goal. It contains:

- Annual goal for each of the postsecondary goal areas (i.e., employment, postsecondary training/education, and independent living)

- Annual goal and short-term objectives or benchmarks, included in the IEP related to the student’s transition services needs

More information on annual IEP goals can be found through the links in Appendix 1A, such as Annual IEP Goals.

Transfer of Rights at Age of Majority

Beginning not later than one year before the student reaches the age of majority, he needs to be informed of any rights that will transfer to him on reaching the age of majority.

Summary of Performance

Summary of Performance is an essential document required by IDEA prior to graduation, but not necessarily a part of the IEP. It assists students in communicating their accomplishments through school and articulate their post-school vision and goals. It contains:

- A statement of the student’s postsecondary goals;

- Academic achievement, including courses of study;

- Current functional performance; and

- Recommendations on how the student can meet their postsecondary goals.

More information on summary of performance can be found through the links in Appendix 1A, such as Summary of Performance.

Some educational staff may not be familiar with some of these concepts and terms. Other questions in this unit describe some of the different parts of the IDEA 2004 requirements for transition planning and services. The Transition Requirements Checklist provides 5 pages of questions, so that you can evaluate if you are meeting the requirements of IDEA. This checklist is compatible with the Indicator 13 Checklist of the National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center. The Glossary in this unit provides a definition of many of these terms.

Are there special considerations in transition planning and services for youth with ASD?

Yes. Transition to adulthood may be especially difficult for individuals with ASD, because of the effects of the underlying challenges in communication, social interaction, sensory regulation, restricted interests and organization. Therefore, students with ASD require individualized instruction and support throughout their transition from school to adult life that uses approaches specific to ASD (Barnhill, 2007; Schall and Wehman, 2009; Seltzer et al., 2004; Simpson, 2005; Wolfe, 2005). Effective transition requires that students have instruction and support that addresses the inherent communication, social, sensory, and organization challenges of ASD. In fact, transition activities will require many of the same types of strategies and supports used with students with ASD in the early years of education.

Many resources are provided throughout this toolkit to help you provide the necessary types of instruction and supports. Appendix 1A: Online Resources supplies links to a number of practical resources on transition and ASD. You will find information and links to useful resources on a variety of supports that can enhance the transition from school to adulthood for youth and young adults with ASD in Unit 2: Supports. Information and resources on effective and evidence based methods and strategies are provided in Unit 3: Expanded Core Curriculum and in the eight subunits of Unit 3.

When should transition planning and services begin?

Transition planning, services, and activities are a multi-year process. IDEA 2004 (§300.320(b)) requires that transition services begin “not later than the first IEP to be in effect when the child turns 16, or younger if determined appropriate by the IEP Team”. This means that for a student who does not need transition services to begin earlier, the IEP teams should start transition planning when he is 15 so that the team can assure that the planning and services have occurred on the IEP in effect when the child is 16 (J. B., personal communication, 2010).In keeping with the individualized nature of the IEP, IDEA 2004 allows the flexibility of starting transition planning at a younger age if this is appropriate as determined by the IEP team. Because of the complex needs of youth with ASD, many transition experts and advocates feel that transition planning must start early.

One of the primary purposes of IDEA (§300.1)(a)) is to "ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for employment and independent living”. Early and long range planning are critical in order for youth with ASD to be prepared for adult life. Many will need the services of multiple adult agencies. It takes time to determine who can do what, who will pay for what services and to put the post-school services and supports in place.

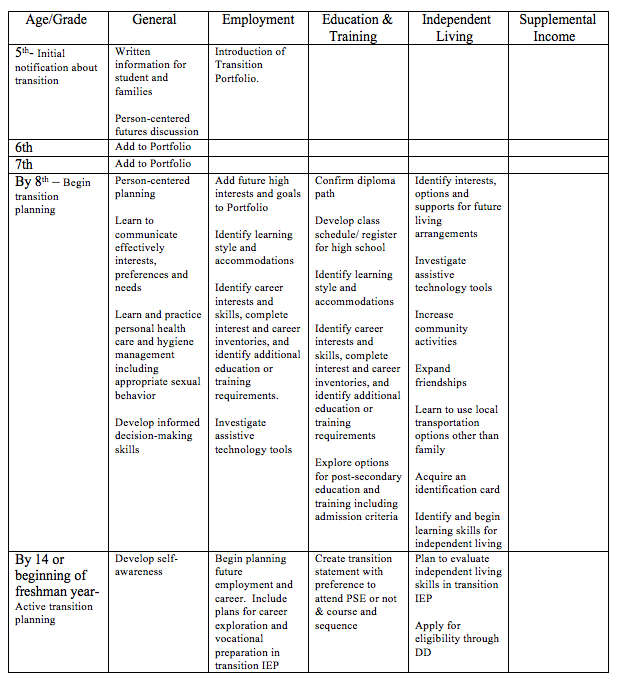

Due to the critical purpose of preparation for adult life, some professionals envision transition as starting as soon as a student enters school. The Oregon Commission on Autism Spectrum Disorder’s Interagency Transition Subcommittee (2010) recommended starting in 5th grade with an initial notification about transition, written materials on transition to families, person-centered futures discussion, and introduction of a transition portfolio. In 8th grade, they recommend beginning transition planning, including person-centered planning, adding high interests and future goals to a transition portfolio, and confirming a diploma path.

The Organization for Autism Research (2006) noted that there is strong evidence that school age programming for students with ASD should consider the transition to adulthood as early as possible and no later than age 14. Studies have found that students who identified post school goals during early adolescence had better post school transition outcomes (Raskind, Goldberg, Higgins, & Herman, 1999, Goldberg, Higgins, Raskind, & Herman, 2003, Gerber, Ginsberg, & Reiff, 1992).

One way to avoid poor outcomes is to begin the transition planning process and transition services early. Appendix 1B: Sample Transition Timelines provides recommendations for transition activities for youth with ASD at different ages to help you to begin the transition process early. By engaging in early transition assessment and planning, the transition IEP team can enhance the number and variety of options that are available to individual students, because there is additional time to provide the foundation needed to access those options.

How does the team determine transition goals and services?

Age appropriate assessment (AATA) forms the basis for defining transition goals and services. Sitlington (1996) defined age appropriate transition as "the ongoing process of collecting data on the individual's strengths, needs, preferences, and interests as they relate to the demands of current and future working, educational, living, personal, and social environments”.

IDEA 2004 specifies that transition services and planning must be based on a comprehensive evaluation of the student’s strengths, needs, preferences, and interests. Therefore, age appropriate transition assessment is an integral and ongoing part of the transition process. It is important to note that age-appropriate transition assessments refer to a student's chronological age, not developmental age. This ongoing process results in refining the measurable postsecondary goals over time.

Age appropriate transition assessment must be systematic and planned and occur over the course of the student's school career. The assessments chosen should provide the answers a team needs to design a plan for the student with youth with ASD. This information is used to develop goals and objectives, as well as to identify support and services needed as an adult. The team needs to determine what information is currently available, what additional information is needed and, what methods of assessment would be most effective.

There is a wealth of currently available information collected in a variety of ways in the general education and special education system that can be used to help plan for transition. For instance, past and current educational, vocational, psychological, social, and psychiatric evaluations in school records can provide important information for transition planning. In addition to these formal and informal assessments, records of attendance data, transcripts, and extra-curricular activities can create a more complete picture of the student.

After reviewing what is currently available, the team can determine what additional assessment is needed to determine the student’s strengths, needs, preferences and interests. Assessments chosen should provide the answers a team needs to develop a plan to actualize the student’s future. More specific information, especially in planning for employment, is usually needed.

Assessment of students with disabilities can take a variety of forms, depending on the information needed for planning and instruction. IDEA 2004 requirements suggest that assessment for transition services should include formal (standardized) tests, informal procedures (e.g. interviews and direct observation), and curriculum-based assessment.

Some traditional formal assessments (e.g., intelligence, achievement, and aptitude tests) are often utilized to gather some of the information. These types of tests are often required for eligibility for adult services.

Informal assessment is as legitimate and often more informative than formal assessments for transition planning. Assessments should include information from structured interviews of the student and parent(s) and structured observations of the student. Information accumulated and documented by observing the student as he participates in various academic, work, community and independent living experiences. Some other valuable types of informal assessment include questionnaires, checklists, and job tryouts.

The decision of which assessments to use to assess each area can be challenging due to the variety of areas that need to be assessed. To alleviate this challenge, links to sites with comprehensive information on age appropriate transition assessment, such as Age Appropriate Transition Assessment Toolkit, is provided in Appendix 1A: Online Resources.

Below is a list of twelve areas that cover basic compliance with the requirement to assess academic and functional performance. Unit 3: The Expanded Core Curriculum includes information and assessment tools for a number of theses areas. Units in parenthesis, such as (Unit 3.1), indicates that more specific information on assessing individuals with ASD in this area is presented in that unit of this toolkit.

- Psychological/cognitive (Unit 3.3)

- Language proficiency/communication (Unit 3.1)

- Social/interpersonal (Unit 3.2)

- Achievement/academic

- Adaptive behavior

- Self regulation and coping (Unit 3.4)

- Self-determination and/or self-advocacy (Unit 3.5)

- Career/vocational (Unit 3.6)

- Independent living and community skills (Unit 3.8)

- Assessment of functional limitations (Unit 3.8)

- Preferences

- Interests

It is important to ensure that the unique needs related to ASD are assessed during transition planning (Schall, 2009; Bolick, 2001), because they significantly impact the youth’s endeavors in reaching his postsecondary goals. Therefore, this toolkit provides more indepth information and tools for assessment in these unique areas in separate units. These include:

Unit 3.1: Communication

Unit 3.2: Social/interpersonal

Unit 3.3: Executive function/Organization

Unit 3.4: Sensory self regulationThe data from all these assessments form the basis for defining goals and services to be included in the IEP. Assessment results are typically found in the present level of academic and functional performance section of the IEP and are used to:

- Identify the student's interests, needs, strengths, and preferences;

- Determine postsecondary goals;

- Develop relevant academic and functional skills instruction;

- Identify appropriate transition services;

- Identify necessary interagency supports and linkages; and

- Evaluate instruction and supports already in place (Noonan, Morningstar, & Clark, 2005).

Are there special considerations in assessment for youth with ASD?

Students with ASD require a creative and careful assessment process that takes into consideration the unique learning style of the person with ASD. Van Pelt (2009) emphasized the importance of highly individualized assessments. The transition team must discuss the best way to elicit a productive student response. Regardless of the tools used, person(s) conducting the assessment must have a firm understanding of ASD in order for the results to be valid. The information below will help you think about what characteristics will adversely affect assessment results and any modifications needed.

Difficulty with standardized tests.

Youth with ASD may not perform well on standardized assessments. It is, therefore, important to consider using other, more natural methods of evaluation and assessment, such as observation (Schall, 2009). In general, descriptive reports that consider functionality and informal assessment results are more helpful than “stand alone” scores.

Unique skills.

Many youth with ASD have unique skills that are not necessarily obvious during a traditional assessment process. They may possess skills suited for a specific “niche” that could lead to successful supported or competitive employment. Identification of these skills often occur through careful observation, interviews with those who know the person well (e.g., family members or the individual) and a longitudinal assessment process. Several hours of traditional assessment or a checklist of vocational skills often misses the person’s unique and most important strengths.

Scattered abilities.

When tested, some areas of ability may be normal, while others may be especially weak. For example, a youth with ASD may do well on the parts of the test that measure visual skills but earn low scores on the language subtests. It is important to have a test that is sensitive enough to reflect these scattered abilities.

Difficulty with imagining.

Youth with ASD tend to have difficulty imagining themselves in different situations, which affects their response to test questions that ask them to do so (Attwood, 2006; Siegel, 2003). Many vocational interest inventories and tests ask individuals to imagine themselves in situations and respond to questions about those situations. If a student with ASD is not able to imagine himself in such situations, the responses he gives to that test must be viewed cautiously.

Difficulty with changes in routine.

In general, youth with ASD respond poorly to changes in their routine. If they experience a testing situation as a change in their routine, they will probably not perform at their highest abilities. They may refuse to do anything for the examiner in this situation. This frequently leads to evaluators reporting that an individual with ASD is uncooperative or unable to be tested. They should be observed in their every day setting to assess the true presence of the skill and abilities.

Prompt dependence.

Youth with ASD may not perform a task, even one that they can do well, unless they are prompted in the same way that they have always been prompted. A skill may be missed, if the examiner has not used the exact words that the teacher does when asking the student to perform a task.

Stimulus over selectivity.

Youth with ASD tend to focus on irrelevant stimuli instead of on relevant aspects of stimulus. (Janzen, 2003; Scott et al., 2000; Siegel, 2003). Because of this, they frequently do not know the salient cues in a situation and have difficulty generalizing skills.

Communication difficulties.

The validity of the results is only as accurate as the student’s understanding. Challenges in communication is one of the four major characteristics of ASD. Youth with ASD may have difficulty understanding and responding to questions or test items.

Sensory over or under reaction.

Youth with ASD may not perform optimally in a test situation due to reaction to sensory input related to lighting, room temperature, crowding, etc.

Unusual motivators.

Youth with ASD often have unusual motivators. The completion of tasks, sensory-based material or activities, special interests, or the pace of an activity may motivate them. Social reinforcement and other typical reinforcement may be of little interest to youth with ASD.

Elements to optimize assessment results

The assessment process may involve new people, tasks, and places, and with limited time for the youth to become familiar with the different aspects of the assessment. All of these can be confusing or anxiety provoking for youth with ASD. Some elements that will help to optimize the results of the assessment process include:

- previous familiarity with the evaluator,

- shorter test periods over multiple sessions,

- advance notice to the youth prior to testing,

- sensory motor preparation for an optimal level of alertness,

- organizational supports such as checklists, visual schedules, templates, visual examples, written directions, and timers,

- visually clear information on what to do, where to do it, where to begin and end tasks, and what to do when one is finished.

Excellent information on the implications of ASD and strategies for effective assessment can be found in Transition to Adulthood: Age Appropriate Assessment.

Effective planning requires a coordinated effort between the student, the family the school and school-based services, as well as with outside agencies that the youth with ASD is currently involved with or might be needed in the future. A team of people with different knowledge and skills can most effectively develop and coordinate an IEP and a transition plan for a student with ASD. These team members should be selected in consultation with the student and the family (Aspel, Bettis, Quinn, Test, & Wood, 1999; Bremer, Kachgal, & Schoeller, 2003; O’Brien, 1987). Members of the transition planning team, may include:

- Student with ASD

- Parent, other interested family members, and/or guardian

- Student’s general education teacher(s), when applicable

- Special education teacher(s)

- District representative

- Transition coordinator and/or vocational educator

- Adult service providers

- Related service providers, such as

- Speech and language pathologists

- Autism specialist

- Occupational therapist

- Psychologist

- Advocacy organization representative

Each team member plays an important role in transition planning and/or services overtime. Transition Coalition provides information about the various roles in transition and how different members of transition teams may participate in the transition process.

Does my student with ASD need to be involved in his transition planning?

Absolutely. Student involvement is a primary component of successful transition planning. Students actively involved in their transition goal planning are most likely to achieve those goals (Kohler & Field, 2003; Martin, Van Dycke, D’Ottavio, & Nickerson, 2007; Shogren et al., 2007). This requires student involvement as an active, respected participant and preferably as a team leader (Wehman, 2006).

Not only does research demonstrate that student involvement in transition planning is a best practice, but IDEA 2004 (300.321[b]) requires the active participation of students in their own transition planning. The law makes it clear that the student is the most important member of the team. Effective transition planning provides the opportunity for youth to learn about themselves and plan for their future.

According to IDEA 2004 (§300.320(b)), the student must be invited to participate in the IEP meeting “if a purpose of the meeting will be the consideration of the postsecondary goals for the child and the transition services needed to assist the child in reaching those goals”. Schools “must take other steps to ensure that the child’s preferences and interests are considered” if the child is not able to attend (IDEA, §300.321(b). In other words, the law requires that student input into the IEP must be obtained even if students choose not to, or are unable to attend the meeting.

Before the meeting, students should be coached and taught the skills they will need to participate in or lead their transition IEP meetings. With support and direct instruction, students with ASD can become aware of their strengths and needs, learn to advocate for themselves, and learn to set and evaluate goals. Over time, students can and should learn to lead their own IEP meetings; it empowers them to be self-determined.

According to Wandry and Repetto (1993), there are four basic transition skills that students with disabilities should have that will help them be active participants in their transition planning process. They are:

- Ability to assess their own skills and abilities;

- Awareness of the accommodations they need because of their disability;

- Knowledge of their civil rights through legislation such as IDEA, the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act;

- Self-advocacy skills necessary to express their needs in the workplace, in educational institutions, and in community settings.

Links with practical ideas and tools for promoting student involvement, such as Student Involvement in the IEP Process are provided in Appendix 1A: Online Resources under two sections: Student Involvement and Instruction Material. More extensive information and links to practical resources to help students develop the skills to become involved in their own transition planning and transition IEP is given in Unit 3.5: Self Determination.

What participation is needed by other agencies?

IDEA 2004 requires that “a representative from any participating agency that is likely to be responsible for providing or paying for transition services” be invited to the IEP meeting. This means a representative from any agency a student may use while in high school or beyond should be invited and encouraged to attend IEP transition planning meetings as soon as possible. Active interagency collaboration between the schools and adult service agencies is critical for effective transition plans (deFur, 2003; Hasazi, Furney & Destefano, 1999; Martin et al., 2002; Repetto et al., 1997; Steele et al., 1990; Wehman, 2001).

Locating, obtaining, and financing needed services for youth with ASD requires navigating complicated public and private service systems. Transition planning should help students and families connect with the adult service system. Bringing everyone to the table and defining roles and responsibilities are important for establishing a continuum of support and a successful transition. This commonly includes:

- Case managers from adult service agencies, e.g. Developmental Disabilities Programs

- Vocational rehabilitation counselor

- Brokerage representative

- Business education partnership or employment network representative

- Residential services representative, when appropriate

- Postsecondary education representative, when applicable

- Social Security representative.

Each organization that is invited to the meeting can explain the process to their agency services and its eligibility criteria, as well as initiate coordinated service. If organization representatives are unable to attend meetings, the school must find alternative ways of involving them in transition planning.

Adult service providers need to be involved long before the student graduates. Several authors advocate for beginning interagency representation in the IEP by the age of 16 (e.g. Barclay & Cobb; Nuehring, M. & Sitlington, P., 2003). Failure to make timely contact with the vocational service provider may result in a student’s underemployment or lack of employment.

Currently, this is a challenging process. According to The Oregon Commission on Autism Spectrum Disorder’s Interagency Transition Subcommittee (2010), “There is a lack of common understanding of the roles and responsibilities of key stakeholders. As a result, there is duplication of efforts, inefficient use or limited resources and less successful outcomes for school leavers.” To alleviate these challenges, they have recommended “An explicit interagency agreement between Seniors and People with Disabilities, Office of Vocational Rehabilitation, Oregon Department of Education, and Oregon Health Authority (and possibly Higher Education) to establish explicit standards for collaboration, communication, consistency, clear performance standards and expected outcomes”. This would define roles and responsibilities of the participating State agencies. In addition, they recommended the establishment of a local Interagency Transition Advisory Committees for individuals with ASD within each County or Region “to advise on practical standards for collaboration with local providers of services and other local community stakeholders for transition age youth with ASD beyond what is recommended or required statewide.” These actions would help distinguish the person within schools and agencies who will accept individual responsibilities in the support and “hand off” process, as well as identify how the receiving agency will assume the supports and responsibilities of the process.

How is person-centered planning related to transition planning?

Some authors suggest that person-centered planning (PCP) is the foundation for transition planning for youth with ASD (e.g. Bolick, 2001; Harrington, 2008; Organization for Autism Research, 2006; Williams-Diehm, & Lynch, 2007). Person-centered planning, also known as personal futures planning or student focused planning, is a team process in which a person with a disability and his chosen support network meet and discuss their vision for a positive future. The team then compares that vision to a measure of the person’s life now and develops an action plan to take steps towards achieving that vision. This plan then acts as a guide for all future actions and choices. In the context of transition planning, the person-centered plan allows the team to personalize and prioritize goals and objectives in the students transition IEP so that they reflect a course of action that will be personally satisfying for the student.

Although a person-centered plan is not required and may be completed only once during high school, such a plan is the best way to find direction for a student’s future while the student is in high school. Studies have revealed that person-centered planning improves the transition outcomes for youth with disabilities (Alwell & Cobb, 2006; Alwell & Cobb, 2007;Test, Fowler, White, Richter & Walker, 2009).

A variety of person centered planning models for transition have been developed that can strengthen the role of youth in preparing for their adult life, including PATH (Planning Alternative Tomorrows with Hope) Whole Life Planning, MAPs (Making Action Plans), PFP (Personal Futures Planning), ELP (Essential Lifestyle Planning) and Circles of Support. “I Wake Up for MY Dream!” discusses the use of 3 of these tools for helping youth with ASD: Circles of Support, MAPs and PATH.

VIDEO: Example of MAP Process Overview

While each method of student-centered planning has unique elements, overall, the methods have the following characteristics in common:

- Discuss who the person is, including his strengths, abilities, interests, goals, preferences, and learning style

- Explore visions for the person’s future keeping in mind that the preferences and desires of the individual are of upmost importance

- Identify obstacles to fulfilling this vision

- Develop an action plan for achieving this vision

Person-centered planning uses a facilitator to bring together the student and a group of people who know the student best. This group can include family members, friends, neighbors, school personnel, etc. The planning should constitute its own meeting as opposed to being one part of an IEP meeting. The emphasis in the meeting is on empowerment of and primary direction from the individual for whom the planning is being conducted. In order for person centered planning to achieve its mission, the focus person must participate fully in the process. It is imperative that the student is heard, regardless of the severity of his disability.

Links to additional information can be found in Appendix 1A under Person Centered Planning.

What is included in the transition IEP plan?

Once a team has completed a transition assessment and person-centered planning, the team is primed to create a youth’s transition IEP. According to IDEA 2004 (§300.320(b), the transition IEP must include a statement, updated annually, of “appropriate measurable postsecondary goals based on age-appropriate transition assessments related to training/education, employment, and independent living skills.” This IEP must also include needed transition services, including courses of study needed to assist in reaching the postsecondary goal.

Educators are most familiar with IEPs that address services to be provided to the student during one school year. The transition requirements of IDEA 2004 require the IEP team to plan several years ahead. It starts with the ultimate, long-term goal(s) and identifies the annual goals and services to accomplish the long-term goal(s). This represents a shift from an emphasis on what is missing in a student’s developmental profile to what skills are necessary for the student to be successful in the next stage of life.

A brief description of the required IEP components for transition services was provided for the question, “What are the core components of transition planning and services?” To summarize, the transition IEP must:

- state the student's postsecondary goals (what he hopes to achieve after leaving high school) in the areas of education/training, employment and, where appropriate, independent living;

- state the present level of academic achievement and functional performance

- break down postsecondary goals into annual IEP goals that represent the steps along the way that the student needs to take while still in high school to get ready for achieving the postsecondary goals after high school; and

- identify and specify the transition services that a student will receive in order to support him or her in reaching the shorter-term IEP goals and the longer-term postsecondary goal, including instruction, related service, community experience, development of employment and other post-school adult living objectives.

- summary of performance is needed for the year in which the student graduates only.

The IEP process for transition services is shown in the figure below.

Source: Adapted from O’Leary (2005) by Morningstar & Pearson (2009)

Writing postsecondary goals can be challenging for educators who are unfamiliar with what needs to be included. Links to excellent websites that provide clear information and examples of postsecondary goals, such as Transition Goals in the IEP are offered under Content of Transition IEP in Appendix 1A: Online Resources.

Transition services are determined by the combination of a student's stated measurable postsecondary goals, corresponding IEP goals, and supports he needs in order to move toward achieving those goals. The transition services in the IEP for youth with ASD will include many of the following elements:

- Instruction in the expanded core curriculum as it related to postsecondary and annual goals (Note: Extensive information and tools for the expanded core curriculum can be found in Unit 3: Expanded Core Curriculum and its eight subunits.)

- Identification of community experiences and skills related to future goals

- Exploration of service organizations or agencies to provide services and support

- Timeline for achieving goals

- Identification of responsible people or agencies to help with these goals

- Clarification of how roles will be coordinated

- Plan for identifying post-graduation services and supports, and obtaining the necessary funding

Extensive information on transition services can be found through the links in Appendix 1A, such as Transition Services.

Are more than academics needed in transition goals and services for youth with ASD?

Yes. Preparing youth with ASD for training/education, employment and independent living goes beyond academic skills. The Oregon Commission on Autism Spectrum Disorder’s Redesign of Education Services Subcommittee (2010) recommended that program planning address “the Expanded Core Curriculum for ASD: communication development, social development, cognitive development, sensory and motor development, adaptive skills development, problem behaviors, organization, and career and life goals.” In accordance with the unique skill development needed by youth with ASD to transition to adult life, The Oregon Commission on Autism Spectrum Disorder’s Interagency Transition Subcommittee (2010) recommended IEP goals and objectives in areas, such as social competence/social cognition, self-determination/self advocacy, and management of stereotyped patterns of behavior. Units 3.1 – 3.8 of this toolkit provide extensive information and links to practical resources for communication, social skills, sensory self-regulation, executive function/organization, self-determination, as well as preparation for training/education, employment and independent living skills for youth with ASD.

How can efforts towards a smooth transition be documented?

Educators need a way to document essential information about each student beyond the information contained in a cumulative folder, such as transition skills learned, job shadowing experiences, paid job experiences, volunteer activities, attendance at job or college fairs, participation in recreation and leisure activities both in school and in the community, and other experiences a student has during their years in school to prepare them for the transition to adult life. This information can be recorded as part of the transition portfolio.

The transition portfolio represents the compilation of each student’s secondary transition process. It is intended to be a practical tool for documenting the efforts of the student, his family, teachers, and other service providers to ensure a smooth transition to post-school opportunities and services. The use of transition portfolios for students in 5th-12th grades is recommended to encourage and support student self-advocacy and self-awareness, while illustrating a student's skills, education, experiences, and their desired outcome. Ideally a transition portfolio moves from grade to grade, school to school, and from high school to adult services (Demchak & Greenfield, 2003). A student or guardian can share or give permission for the school to share his portfolio, when he is being referred to an adult agency and documentation is required for eligibility and plan development. The portfolio contains everything the service provider needs. The student can also use the portfolio to help obtain employment and to assist in getting needed accommodations in various employment and educational settings. Finally, the portfolio provides a tool for accountability and can help parents to understand what is being done in school to prepare their child for adulthood.

Some high schools offer a Transition Class or have a Life Skills classroom, in which transition portfolios can be developed and kept. Activities at the elementary and middle school levels may be initiated in the resource room.

A variety of topics and number of sections can be included in a transition portfolio. The portfolio should be tailored to the individual needs of each child and assist the student as he moves toward adulthood. The following includes potential sections and information you might consider including in your students’ transition portfolios. A three-ring binder, manila folder or electronic folder can be used.

Personal Information. Contains general information about the student that is personal in nature or provides basic information relating to the student’s planning. Information may include the personal information sheet, transition planning worksheets, student questionnaires, and parent inventories.

Education. Contains the components that are most relevant to the student’s education, such as IEP goals and objectives, learning styles inventories, information relevant to post-secondary education, school awards and honors, and any other evidence of activities that documents accomplishment.

Career. Contains information related to the student’s career and vocational plans. Suggested items would include career interest and skills inventories, sample resumes, letters of recommendation, summaries of job shadows and work experiences, career clusters worksheets, and vocational program observation forms.

Community/Independent Living. Could include skills inventories related to residential and community access, documentation of community experiences, or other items that address the student’s abilities and experiences related to accessing the community and independent living.

Inter-agency Linkages. Could include the agency planning chart and copies of correspondence with agency representatives and any plan that has been developed through an agency.

Communication/Social Interaction. Could include skill inventories and documentation of social activities that involve the student.

Self-determination. Includes Self Folio introduced in Unit 3.5 of this toolkit.

Recreation and Leisure. Includes information related to home, school or community recreation and leisure activities, such as skill inventories, interest worksheets, and documentation of activities.

Miscellaneous. Includes information that the student would like to save that does not naturally fit in any of the listed categories.

Appendix 1A: Online and Other Resources

Freely available resources are available across the following topics:

- Understanding Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Comprehensive Training Websites

- Oregon

- National

- ASD and Transition

- Age Appropriate Transition Assessment

- Student Involvement

- Person-Centered Planning

- Contents of Transition IEP

- Transition Portfolio

- Instructional Material

- Online Videos

- Understanding ASD

- Understanding Transition

- Online and Others Training for Transition

- Adult Service Organizations

- Practical Books Available on Loan

Some websites are listed in several sections because of their relevance to more than one area.

UNDERSTANDING AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER

Adolescence and Adulthood - This chapter from Higher Functioning Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism provides an overview of characteristics. Although the incidence of ASD has increased dramatically since this was written, the characteristics have not changed.

Autism Spectrum Disorder Fact Sheet - National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. This fact sheet provides information on symptoms of autism, how someone can be diagnosed, treatments, research, links to useful websites and much more.

Autism: Reaching for a Brighter Future - Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence. These guidelines offer comprehensive information on ASD and a section on Community Transition.

Autism Society - This site provides information about autism, symptoms, education and treatment options, tips on how families can learn to cope together and links to websites that provide useful information on how to get services.

Autism Spectrum Disorder: Evaluation, Eligibility, and Goal Development (Birth-21) Technical Assistance Paper - 2010, Oregon Department of Education. This guide explains how to evaluate and determine eligibility of individuals who are suspected to have an Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). It is in the process of being updated.

Behaviors That May Be Personal Challenges For A Student With An Autism Spectrum Disorder - These forms, which are adapted from the Technical Assistance Manual on Autism for Kentucky Schools by Nancy Dalrymple and Lisa Ruble, provide checklists for what may be personal challenges for individuals with ASD.

Columbia Regional Program - Information and resources for educators and parents on ASD, serves Multnomah, Clackamas, Hood River, and Wasco counties in Oregon

Indiana Resource Center for Autism (IRCA) - Indiana Institute on Disability and Community. This site provides information and research about ASD.

OASIS @ MAAP - This site provides articles, educational resources, links to local, national and international support groups, sources of professional help and more.

Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI) - OCALI provides information and resources about ASD and transition.

Organization for Autism Research (OAR) - This site offers evidence-based information about ASD.

Recognizing Autism - Autism Internet Modules. This site offers modules about Recognizing Autism. The modules include Assessment for Identification, Restricted Patterns of Behavior, Interests, and Activities, and Sensory Differences. (This site requires you to login to gain access to the modules. Sign up is free.)

Who Are Higher Functioning Young Adults with Autism? - This chapter from Higher Functioning Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism discusses the challenges of adolescence and young adulthood. Although the incidence of ASD has increased dramatically since this was written, the characteristics have not changed.

COMPREHENSIVE TRANSITION WEBSITES

Oregon

Oregon Youth Transition Program (YTP) - This provides information on its comprehensive transition program for youth with disabilities and resources for transition.

Reference Materials from SPR&I Trainings - Oregon Department of Education. This page contains Secondary Transition reference materials presented at 2008 through 2015 Systems Performance Review and Improvement (SPR&I) training events.

Secondary Transition for Students with Disabilities - Oregon Department of Education. This site provides information and resources about transition.

Transition Community Network - This site offers resources on transition for students, parents, teachers, administrators, potential and current employers, and professionals in agencies that provide services to students with disabilities.

Transition Reference Materials 2010-11 Section 4 - Oregon Department of Education. This document provides a transition standards checklist and other secondary transition resources.

National

Building the Legacy: Secondary Transition - This page provides links to topic briefs, training materials, guides and Q & A for secondary transition.

Charting a Course for the Future - A Transition Toolkit - Colorado Department of Education. This site provides information and tools necessary in creating a comprehensive and individualized transition process.

DCDT Practioner-oriented Resources - Division on Career Development & Transition (DCDT) and National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC). This site provides links to many publications about transition such as:

- Tips for Transition

- Transition-related Planning, Instruction, and Service Responsibilities for Secondary Special Educators (pdf)

- Age Appropriate Transition Assessment

- Evidence-Based Secondary Transition Predictors of Improved Post-school Outcomes for Students with Disabilities

- Student Involvement in the IEP Process

- Improving Post-School Employment Outcomes: Evidence-Based Secondary Transition Predictors

- Improving Post-School Independent Living Outcomes: Evidence-Based Secondary Transition Predictors

IDEA (2004) Regulations Related to Secondary Transition - Division on Career Development & Transition (DCDT). This document is designed to provide a quick reference to regulations, comments, and discussions related to secondary transition.

IDEA 2004: Transition Services for Education, Work, Independent Living - Wrightslaw.com. This site provides the definition of "Transition services" and links to useful articles and publications.

Institute for Community Inclusion (ICI) - This site provides resources and publications for secondary transition and the inclusion of individuals with disabilities in all facets of adulthood.

National Center on Secondary Education and Transition (NCSET) - This site provides resources, technical assistance, and information related to secondary education and transition for youth with disabilities.

National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities (NICHCY) - This site offers information and resources on disabilities and special education for children and youth from birth through 21 years. It includes a thorough section on transition.

National Technical Assistance Center on Transition (NTACT) - NTACT has many resources on transition, including a transition assessment toolkit, sample planning tools from states, examples of measurable postsecondary goals, evidence-based practices and a lesson plan library.

People Make it Happen - Transition Coalition. This booklet includes information about the various roles in transition and how different members of transition teams may participate in the transition process.

Secondary Transition of Youth with Disabilities - National Dissemination Center for Youth with Disabilities (NICHCY). This site offers an entire suite on Transition to Adulthood, which includes nine separate webpages.

Technical Assistance on Transition and the Rehabilitation Act (TATRA) - PACER Center. This site provides information and training on transition planning, the adult service system, and strategies that prepare youth for successful employment, postsecondary education, and independent living outcomes.

Transition Coalition - This site provides information and free research-based online training on topics related to the transition from school to adult life for youth with disabilities.

Transition Tips Search - Transition Coalition. This site offers a searchable database of transition tips and resources. Search, browse, or add your own tip to the tips database. Tips are available in the major areas of transition planning and are submitted by practitioners describing transition practices and resources they have found helpful.

Transition to Adulthood - National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities (NICHCY). This page provides a quick description of transition.

Transition Goals in the IEP - National Dissemination Center for Children with Disabilities (NICHCY). This page provides a description of IEP transition goals and examples.

Training Modules for the Transition to Adult Living: An Information and Resource Guide - California Services for Technical Assistance and Training (CalSTAT). This guide offers a comprehensive transition handbook for students, parents, and teachers. The site also offers three training modules for service providers, administrators, and families.

ASD AND TRANSITION

Autism Spectrum Disorders and the Transition to Adulthood - Virginia Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Student Services. This is a comprehensive guide to ASD and transition.

Evidence-Based Practices for Helping Secondary Students with Autism Transition Successfully to Adulthood - David W. Test University of North Carolina at Charlotte and. National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center. This presentation shows the steps in self-directed IEP process.

Life Journey Through Autism: A Guide for Transition to Adulthood - Organization for Autism Research (OAR). This publication provides an overview of the transition-to-adulthood process.

Making the Move to Manage Your Own Personal Assistance Services (PAS) - A recently released toolkit through the National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability-Youth, the Office of Disability Employment Policy (ODEP). This toolkit assists youth in strengthening some of the fundamental skills essential for successfully managing their own PAS: effective communication, time-management, working with others, and establishing professional relationships.

Ontario Adult Autism Research and Support Network (OAARSN) - This Canadian website offers information and communication tools to connect adults with Autism, family members, caregivers, friends, support workers, teachers, administrators and policymakers.

Teens and Autism - This page provides links for a variety of autism and teen related subjects.

Transition Toolkit - Autism Speaks. This toolkit is a guide to assist families on the journey from adolescence to adulthood.

Transitioning to Adulthood - Bellefaire JCB/Monarch Center for Autism. This site offers information on transitioning to adulthood, transition planning, supported living, person centered planning, and more.

Transition to Adulthood Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) - Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI). These are comprehensive guides for parents and professionals on the process of transition to adulthood for individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Transition Planning - ASD Concepts, LLC. This site offers a transition timeline, along with 10 Do’s and Don’ts for school to work transition planning for individuals with ASD.

Age Appropriate Transition Assessment

Age Appropriate Transition Assessment - National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC). This is a fact sheet about age appropriate transition assessment.

Age Appropriate Transition Assessment Toolkit - National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC) This toolkit includes how to select instruments, why and how to conduct assessment, and samples of informal and formal assessment tools.

Ansell-Casey Life Skills Assessments (ACLSA) - Casey Family Programs. This is an assessment tool for evaluating the life skills of youth and young adults.

Assessing Students with Significant Disabilities for Supported Adulthood: Exploring Appropriate Transition Assessments - (2009) Morningstar, M. E., National Center on Secondary and Transition Technical Assistance. This presentation is about tools for assessing students with severe cognitive disabilities.

Making Assessment Accommodations: A Toolkit for Educators - The Council for Exceptional Children. This toolkit provides an overview of assessment accommodations and modifications for students with disabilities.

Parent Transition Survey - Transition Coalition. This survey addresses those areas identified for transition planning and assists the IEP team in making decisions, including post secondary education, vocational training, integrated employment, continuing and adult education, adult services, independent living skills, and community participation. Parents rank the areas of need.

QuickBook Of Transition Assessments - Transition Services Liaison Project (TSLP) This guide provides tip for transition planning and transition assessment tools.

Transition Assessment Matrix - Iowa Transition Assessment. This is a comprehensive site on transition assessment.

Transition Assessment and Planning Guide - University of Montana Rural Institute. This tool assists Transition IEP teams to identify postsecondary goals, relevant skills and experiences that will lead to the achievement of those goals, the students present levels of performance within environments that they find meaningful, and accommodations and supports that are currently successful for the student.

Transition Assessment Resource Manual - 2008, Connecticut State Department of Education. This resource for transition assessment is found in the section on secondary transition. (Scroll down to the “Secondary Transition” section.)

Transition Planning Inventory for Students and Families - This is a form to help students and parents sit down to identify their future plans prior to attending transition planning meetings.

Student Involvement

Goal Setting for Transition-Age Students - S. B. Palmer & K. Williams-Diehm, Division on Career Development & Transition (DCDT) a division of The Council for Exceptional Children. This is a fact sheet on student involvement in the IEP process.

Going to College - This site provides information about college life with a disability. It includes video clips, activities and additional resources that can help prepare a high school student with a disability for college.

Person-Centered Planning

Circle of Support - Bellefaire JCB/Monarch Center for Autism. This site provides a description of the Circle of Support.

Inclusion Articles - Inclusion Press International & The Marsha Forest Centre. This site offers articles about PATH, MAPS, and Circles of Support.

It's Never Too Early It's Never Too Late: A Booklet about Personal Futures Planning - Minnesota's Governor's Planning Council on Developmental Disabilities. This 51-page booklet is designed for people with developmental disabilities, their families and friends, case managers, service providers, and advocates. It includes an introduction to Personal Futures Planning, ideas for finding capacities, building a network, and steps in the planning process

“I Wake Up for MY Dream!” Personal Futures Planning Circles of Support, MAPS and PATH - K. Davis, Indiana Institute on Disability and Community. This page discusses the use of 3 tools for helping individuals with ASD: Circles of Support (Friends), MAPS (Making Action Plans) and PATH (Planning Alternative Tomorrows with Hope).

The Learning Community for Person Centered Practices - This site provides training in essential lifestyle planning and person centered practices.

Making Action Plans Student Centered Transitional Planning (MAPS) - 2001, Paul V. Sherlock Center, Rhode Island College This article describes the MAPS process.

Organization for Autism Research: Scholarship Program - Scholarships for individuals diagnosed with ASD.

PATH: Planning Alternative Tomorrows with Hope - ASPIRE: Autism Support Project, Ontario Adult Autism Research and Support Network (OAARSN). This article offers some ideas about PATH and CIRCLES as planning tools for better lives and more secure futures for young adults with ASD. The article also includes questions and answers.

Person Centered Planning - PACER Center. This page provides an overview of Person Centered Planning, with a significant number of online resources.

Person Centered Planning: A Tool for Transition - 2004, National Center on Secondary Education and Transition (NCSET) & PACER Center. This document is written for parents and provides an overview of Person-Centered Planning, including action steps, young adult participation in the process, and developing natural supports. There are numerous links to additional resources.

Person Centered Planning Education Site - Employment and Disability Institute, Cornell University. This site provides an overview of the person-centered planning process, a self-study course covering the basic processes involved, a quiz section, a compendium of readings and activities, and a variety of links and downloadable resources. The Course 5 Series: Popular Person-Centered Tools includes Objectives and Framework, Essential Lifestyle Planning, MAPS, Personal Futures Planning, PATH, and Circles of Support.

Planning for the Future - Transition Coalition. This workbook is designed to help students, their families, and professionals to plan for life after high school. It uses a person-centered approach to identify student strengths and uses a problem-solving approach to develop a plan of action and a vision for the future.

A Workbook for Your Personal Passport - Allen, Shea & Associates This workbook is for people with developmental disabilities and their friends and families who want to learn more about person-centered planning.

Contents of Transition IEP