-

Preparing Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder for Adulthood: A Transition Toolkit for Educators

UNIT 3: The Expanded Core Curriculum

Key Questions

- What is the expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD?

- Why is the expanded core curriculum necessary?

- Why does the expanded core curriculum include these domains?

- Why can't these domains be addressed in the core curriculum?

- Does this mean there is one curriculum I can use with my student(s) with ASD?

- When should I start teaching within the domains of the expanded core curriculum?

- How can instruction in the domains of the expanded core curriculum be fit into the busy school day?

- What skills should I teach within each domain of the expanded core curriculum?

- What evidence-based practices can be used to teach skills in the expanded core curriculum?

- What approaches are important for teaching youth with ASD?

Appendices- Appendix 3A: Online and Other Resources

- Appendix 3B: Evidence-Based Practice

- Appendix 3C: Glossary of Terms

by Phyllis Coyne

This unit provides an introduction to the eight domains of instruction that should be addressed to prepare youth with ASD for the transition from school to adult life. Additional training or consultation may be needed. Units 3.1 – 3.8 present more substantial information and resources for individual domains.

This is a resource for you and is designed so that you can return to sections of the unit as you need more information or tools. You do not need to read this unit from beginning to end or in order. Feel free to print this unit for ease of reading or as an accessible reference. Links to questions, appendices and online resources are provided so that you can go directly to what is most relevant to you at the time.

What is the expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD?

As used in this toolkit, the expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD is the body of knowledge and skills that are impacted by ASD and are needed by youth and young adults with ASD in preparation for their desired training/education, employment, independent living and community participation. Therefore, the expanded core curriculum addresses the underlying characteristics of ASD and skills for adult living.The knowledge and skills that students are expected to acquire to earn a high school diploma is commonly known to educators as the core curriculum. Due to the complex and pervasive nature of ASD, these youth need the expanded core curriculum in addition to the core academic curriculum of general education. The expanded core curriculum provides a framework for assessing students, planning individual goals and providing instruction.

Because the expanded core curriculum in this toolkit is focused specifically on youth and young adults age 14 – 22, it differs slightly in wording and content from the 2010 subcommittee recommendations to the Oregon Commission on Autism Spectrum Disorder. The Commission’s Redesign of ASD Education Services Subcommittee recommended that, “For each individual learner, program planning addresses the Expanded Core Curriculum for ASD: communication development, social development, cognitive development, sensory and motor development, adaptive skills development, problem behaviors, organization, and career and life goals.” The Commission’s Interagency Transition Services Subcommittee recommended that, “Every student with ASD should have IEP goals and objectives that reflect the Preferences, Interests, Needs and Strengths (PINS) in the unique academic and functional skills required to effectively transition into adult life. For example: Social Competence/Social Cognition; Self determination/self advocacy; management of stereotyped patterns of behavior, etc…”.

In order to reasonably prepare youth with ASD to meet their desired postsecondary goals in training/education, employment and independent living, the expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD designed for this toolkit includes three types of domains:

- Domains specific to the inherent characteristics of students with ASD, which include communication, social skills, executive function/organization and sensory self regulation;

- A critical and evidence-based domain for transition, self-determination; and

- Domains related to transition requirements of IDEA 2004, which include employment, postsecondary training and/or education, and independent living. Note: These domains are not listed last because they are least important; rather they are listed last because success in each of them requires competence in skills or supports from the preceding domains.

The expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD consists of eight domains:

Communication skills to communicate intentionally and effectively, including expressive and receptive skills, for school, home, work and the community. See Unit 3.1 for detailed information and resources for communication.

Social skills needed to respond appropriately and participate actively in social situations at school, home, work and the community. These may include skills and concepts, such as initiating, maintaining, and ending conversations, social understanding and managing emotions. See Unit 3.2 for detailed information and resources for social skills.

Executive function/organizational skills to organize, plan, stay on track, problem solve and change actions and plans easily and smoothly. See Unit 3.3 for detailed information and resources for executive function/organization.

Sensory self-regulation skills to self-monitor and self regulate one’s own sensory state. See Unit 3.4 for detailed information and resources for sensory self regulation.

Self-Determination skills to enable students to become effective advocates for themselves based on their own needs and goals. See Unit 3.5 for detailed information and resources for self determination.

Employment knowledge and skills that enable youth with ASD to move toward working as an adult, including exploring and expressing preferences about work roles; assuming work responsibilities at home, school and community; understanding concepts of reward for work; participating in community based job experiences; and learning about jobs and adult work roles at a developmentally appropriate level. See Unit 3.6 for detailed information and resources for preparation for employment.

Postsecondary training and/or education enable youth with ASD to move toward their goals after graduating from high school. See Unit 3.7 for detailed information and resources for preparation for postsecondary training and/or education.

Independent and community living skills needed to function as independently as possible at school, home, work and the community, such as personal grooming, time management, cooking, cleaning, clothing care, and money management. See Unit 3.8 for detailed information and resources for skills for independent living and community participation.

Why is the Expanded Core Curriculum necessary?

IDEA 2004 clearly states that the purpose of special education is “to ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique need and prepare them for further education, employment and independent living…” (20 U.S.C. § 1400(d)). However, IDEA’s intent to prepare youth with disabilities, including those with ASD, for life beyond high school is not being met. Billstedt, Gillberg & Gillberg (2005) found that 92% of the 114 adults with ASD studied were not employed or engaged in education/vocational training, and did not live independently. There was no difference between adults who were considered higher functioning and those with a more classic presentation. These poor outcomes will not change unless the underlying characteristics and critical skills for adult life are addressed directly and comprehensively.Frequently youth with ASD, who have the academic skill to graduate with a standard or higher designation diploma, do not receive specialized instruction in important social and functional living skills that would increase their success in higher education and employment. As a result of the lack of specialized instruction in these important areas, too many students with higher academic abilities are not able to achieve successful employment or independent living.

The success that youth and young adults with ASD achieve in the transition from school to adult life is significantly influenced by the instruction and supports that they receive. Preparing them for further education, employment and independent living extends far beyond the core curriculum of academic skills found in most schools. Many concepts and skills casually and incidentally learned by typical students must be systematically and sequentially taught to students with ASD. Therefore, the Oregon Commission on Autism Spectrum Disorder’s Redesign of Education Services Subcommittee (2010) recommended that program planning address “the Expanded Core Curriculum for ASD: communication development, social development, cognitive development, sensory and motor development, adaptive skills development, problem behaviors, organization, and career and life goals.” In accordance with the unique skills needed by youth with ASD to transition to adult life, the Commission’s Interagency Transition Subcommittee (2010) recommended IEP goals and objectives in areas, such as social competence/social cognition, self-determination/self advocacy, and management of stereotyped patterns of behavior.

The expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD focuses on quality, individualized instruction and supports throughout their transition from school to adult life that use best practices for this population. The more skills individuals with ASD have the less support they will need. If youth do not have these skills or needed supports in place, they cannot become productive, independent adults with full citizenship. Therefore, the expanded core curriculum is not an optional part of the student's educational program but, perhaps, the most essential part.

Why does the expanded core curriculum include these domains?

All of the domains of the expanded core curriculum address core challenges of ASD or are essential for the transition to adult life. Effective transition requires that students have instruction and support that addresses the inherent communication, social, executive function/organization and sensory challenges of ASD, as well as adult living skills. While these domains are predominantly interrelated and interdependent, each is recognized as a domain that warrants specific instruction, even if skills are often embedded and taught as part of a routine or activity. It is essential for youth with ASD to develop competencies in each of these areas or have the needed supports in order to reach their potential to live independently, have appropriate career opportunities, and live rewarding and fulfilling lives.Although there has been no research on the expanded core curriculum per se, research has shown the efficacy of instruction in each domain either for youth with disabilities in school to work transition or specifically for youth with ASD. The information below explains the critical nature of each domain:

Communication Skills

Challenges in communication are one of the four major characteristics of ASD. Whether youth with ASD are nonverbal or verbal, they experience difficulty in communicating or have unusual methods of doing so. The importance of communication and language skills to adult outcomes is profound (Ogletree, Oren, & Fischer, 2007; Wetherby & Prizant, 2000). It is essential that transition planning for students with ASD address reliable and universally understood means of communicating. Once a young adult enters the workplace, he must have the ability to communicate with employers, co-workers, and possible customers whether verbally, with an augmentative or alternative communication device or other means (Schall & Harrington, 2008; Wehman, 2009). Without these communication skills, youth with ASD may use less conventional behavior to communicate, which distresses others at school, work, home, and in the community. See Unit 3.1 for detailed information and resources for communication.

Social Skills

According to White, White, Keonig, & Scahill (2007) a profound deficit in social reciprocity skills is the core underlying feature of ASD and is a major source of impairment regardless of cognitive or language ability. Unlike their neurotypical peers, young people with ASD do not naturally understand or learn social skills. Even with careful instruction, their limitations in social skills do not remit with age. In fact, social challenges and distress may increase in adolescence, because social situations become more complex and the student is more aware of his social disability (White, Koenig and Scahill, 2007). Poor social skills are a major reason so many individuals with ASD have difficulty securing and holding a job (Barnhill, 2007; Hillier, Campbell et al., 2007; Muller, Schuler, Burton & Yates, 2003; Wagner, Newman, Cameto, Levine & Garza, 2005). In addition, social challenges impact relationships and integration into the community (Filler & Rosenshein, 2008). Therefore, youth with ASD have an irrefutable need for a range of instruction and support in social skills throughout their school career and beyond (Schall & Wehman, 2004; Stichter & Conroy, 2006). It is so basic that it can often mean the difference between a poor adult outcome and a satisfying and fulfilling life as an adult. See Unit 3.2 for detailed information and resources for social skills.

Executive Function/Organization

Although not a diagnostic criteria, executive function is considered to be a core cognitive deficit of ASD (Frith, 1989; Hughes et al., 1994; Ozonoff, 1995; & Ozonoff & Griffith, 2000). Problems with attention control and attention shifting, planning and goal setting, flexibility, organization, time management, memory, self-regulation and metacognition have consistently been described as traits of individuals with ASD (Adreon & Durocher, 2007; Coyne, 1996; Filler & Rosenshein, 2008; Hume, Loftin & Lantz, 2009, Ozonoff & Griffith, 2000, VanBergeijk, Klin & Volmar, 2008; Webb, Patterson, Syverud, & Seabrooks-Blackmore, 2008). Whether mild, moderate or severe, executive function challenges significantly affect every day functioning at school, work, community and home. Therefore, it is essential to address executive function challenges (Hume, et al., 2009; Schall & Wehman, 2009). See Unit 3.3 for detailed information and resources for executive function/organization.

Sensory Self-Regulation

The Diagnostic and Standards Manual, 5th edition, now includes an “unusual response to sensory information” as a diagnostic criteria for Autism Spectrum Disorder. Already, many professionals, professional organizations and state departments of education include over and under responsiveness to sensory input as the fourth major characteristic of ASD. For instance, the Oregon Department of Education requires an “unusual response to sensory information” to be eligible for special education services under the category of Autism/ASD.

Challenges in responding to sensory input influences all aspects of a youth with ASD’s life and as youth with ASD move towards adulthood more sensory self-regulation is expected from them. Sensory self-regulation difficulties of youth and young adults with ASD can not only create frustration and anxiety, but also may further increase social isolation and impact future employment. Without strategies to self-regulate, youth with ASD may have difficulty coping in a variety of environments. Wehman (2004) asserted that transition programs for students with ASD must include coping skills. See Unit 3.4 for detailed information and resources for sensory self-regulation.

Self-Determination

Instruction in self-determination is now widely recognized in the literature as an evidenced- based practice in the education of students with disabilities, particularly regarding facilitating students’ involvement in transition planning (e.g. Cobb, Lehmann, Newman, Gonchar, & Alwell, 2009; Getzel & Thoma, 2006; Stodden, Galloway & Stodden, 2003; Hasazi, Furney, & DeStefano, 1999; Schall, 2009; Sitlington and Clark, 2005; Thoma & Wehmeyer, 2005; Williams-Diehm & Lynch, 2007). Research shows that students with self determination skills are better prepared to participate in planning for their future and in making decisions (deFur, 2003; Fullerton & Coyne, 1999; Malian & Nevin, 2002; Price, Wolensky, & Mulligan, 2002; Wehmeyer & Schwartz, 1997).

According to Hutchinson, Versnel, Chin, & Munby (2008), without self-determination training, youth and young adults with ASD are unaware of their own strengths and weaknesses, so they cannot advocate for themselves. With self-knowledge and self-determination skills youth are able to articulate their postsecondary dreams and goals, strengths, and interests, as well as reach out for assistance in order to benefit from support services (Lindstrom, Paskey, Dickinson, Doren, Zane, & Johnson, 2007). In addition, students who are expected to take responsibility for planning their transitions and who are trained to engage in self-determination activities early in secondary school have been shown to take greater responsibility for their lives after school (deFur, 2003). See Unit 3.5 for detailed information and resources for self-determination.

Preparation for Employment

The regulations for IDEA 2004 (20 U.S.C. § 1400(d)) acknowledged that a primary purpose of public education for children and youth with disabilities is to “… meet their unique needs and prepare them for… employment…”. Measurable postsecondary goal(s) and annual goals to reasonably enable the youth to reach the goal(s) are required for employment.

Research has revealed poorer employment outcomes for young adults with ASD, regardless of cognitive or verbal ability, than any other disability. For instance, Cedurland, Hagberg, Billstedt, Gillberg & Gillberg (2008) found that although the employment outcomes for males with Asperger’s were better than males with autism, only 12% were employed full time and only 1% of the 12% were employed in an area in which they had training or education.

Because unemployment and underemployment have been a major problem for individuals with ASD, this portion of the expanded core curriculum is vital to students, and should be part of the expanded curriculum for even the youngest student with ASD. Much of the knowledge and skills offered to all students through career/vocational education can be of value to students with ASD. However, this type of instruction will not be sufficient to prepare students with ASD for adult life, since it assumes a basic knowledge of the world of work and work behaviors.

Preparation for employment in the expanded core curriculum provides students with ASD with the opportunity to explore strengths and interests in a systematic, well-planned manner; to learn work behaviors, such as following instructions, being punctual and responsible, taking criticism, working well independently or as a member of a team, communicating effectively, integrating oneself into a new work environment; to learn occupational skills such as how to search and apply for jobs; and to experience community based work experience. See Unit 3.6 for detailed information and resources for preparation for employment.

Preparation for Training and/or Education

The regulations for IDEA 2004 (20 U.S.C. § 1400(d)) acknowledged that a primary purpose of public education for children and youth with disabilities is to “…meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education…”. To comply with the regulations and law, the Office of Special Education Programs (OSEP) is recommending that students have at least one measurable postsecondary goal and annual goal that covers the areas of education or training. This may include, but is not limited to, goals for short-term employment training (e.g., Workforce Investment Act, Job Corps), vocational technical school, community college, or university.

Although the vast majority of individuals with ASD have average to above intelligence, a small percentage of individuals with ASD have attended and graduated from postsecondary education (Greene, et al., 2000; Howlin, 2003; Howlin, et al., 2004). Individuals with ASD need more than being intellectually capable of the level of training or education, being talented in one particular area, or being fully included to succeed in training or postsecondary education environments.

Youth with ASD require direct instruction in a range of skills and supports in order to prepare them to succeed both in learning and in transitioning to training or educational environments, where more is expected of them. See Unit 3.7 for detailed information and resources for preparation for postsecondary training and/or education.

Independent Living and Community Skills

The regulations for IDEA 2004 (20 U.S.C. § 1400(d)) acknowledged that a primary purpose of public education for children and youth with disabilities is to “prepare them for independent living”. Measurable postsecondary goal(s) for independent living and annual goals to reasonably enable the youth to reach the goal(s) are required, when deemed appropriate by the transition IEP team.

Studies have revealed poor outcomes for independent living and community participation for individuals with ASD regardless of cognitive or verbal ability. For instance, in a one-year post graduation interview of young adults with ASD or their parents in the 4 counties served by Columbia Regional Program, most of the young people were reportedly living with their family or in a foster home; none were on campus or living independently (P. J., personal communication, 2010). These outcomes are not limited to those with classic autism. The research on those with Asperger’s Syndrome indicates that the gap between IQ and independent living skills is wide (Green et al., 2000; Lee & Park, 2007; Myles et al., 2007).

Given the learning and behavioral characteristics of ASD, it is essential that students receive regular, frequent instruction in independent living skills (also referred to as daily living skills or life skills) to make a successful transition to independence in their own communities (Hendricks, Smith & Wehman, 2009). The curricular needs in independent livings are broad, as they include skills in personal care, home maintenance, leisure and recreation, transportation, money management, personal safety, health care, and community participation.

Some independent living skills are addressed in the existing core curriculum, but they often are introduced as splinter skills, appearing in learning material, disappearing, and then re-appearing. This approach will not adequately prepare youth and young adults with ASD for adult life. Traditional classes in subjects, such as home economics and family life are not enough to meet the learning needs of most students with ASD, since they assume a basic level of knowledge and skills acquired incidentally. Therefore, a specialized curriculum is needed that addresses the learning style of students with ASD. See Unit 3.8 for detailed information and resources for skills for independent living and community participation.

Why can’t these domains be addressed in the core curriculum?

Although it may appear that many of the domains of the expanded core curriculum could be learned within the existing core curriculum, there is compelling evidence that relying on the skills taught as part of the core curriculum is inadequate. Generally, the skills appear and disappear in the core curriculum and assumptions are made that students learn and apply these skills. Youth with ASD have the capacity to learn a variety of concepts and skills. However, they learn differently and it is critical that instruction is designed with their individual learning styles in mind. Skills must be carefully, consciously, and sequentially taught to them.Even if universal design principles are applied, the existing core curriculum does not provide the appropriate emphasis on the skills that youth with ASD need to reasonably enable them to meet their desired postsecondary goals for training or education, employment and independent living. The existing core curriculum simply does not address the critical skill areas of the expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD in an effective manner.

Does this mean there is one curriculum I can use with my student(s) with ASD?

No. The expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD refers to the body of knowledge and skills that are impacted by ASD and are needed by youth with ASD in preparation for adulthood rather than a particular curriculum. There is no one curriculum that will meet the needs of every student with ASD. Although youth with ASD share major difficulties in the normal acquisition of communication, social, executive function/organization, and sensory self-regulation skills, all of them have significant individual differences, which have to be taken into account. They vary in the degree of their symptoms and the way in which they manifest. In addition, each youth with ASD will have individual postsecondary goals based on age appropriate transition assessment that will drive the skills that they will need for adult living.When should I start teaching within the domains of the expanded core curriculum?

The expanded core curriculum for students with ASD will be difficult to complete in 12 years of education, especially for students who are high academic learners. Because of the complex and pervasive nature of ASD, direct instruction using best practices should be provided in these areas from kindergarten through high school. Children and youth with ASD require years of instruction and their challenges do not diminish with age.Beginning instruction in these skill areas when an individual with ASD is an adolescent does not allow adequate time to develop critical skills for adult living. Although this toolkit is designed to enable members of the transition IEP team to provide instruction in these essential skill areas to youth with ASD, many of the tools can also be used with younger students.

How can I fit instruction in the domains of the expanded core curriculum into the busy school day?

Instruction that appropriately addresses all the skill areas of the expanded core curriculum requires that a sizable amount of time be allocated. Community-based instruction is a key to generalization and future success. The best way to avoid having to teach and re-teach skills in every new environment is to teach skills in the environment where it will be used. This is not only best practice, but IDEA 2004 identifies community experience as a part of transition services.At this time, no single, simple method has been developed that assures that students with ASD can access both traditional and the expanded core curricula within the school day. However, several approaches for fitting the expanded core curriculum into a high school setting have been used effectively.

One approach is to schedule “elective” for credit classes in domains of the expanded core curriculum for students with ASD in middle schools and high schools. This can add a balance of required hours for core academic courses and time for the expanded core curriculum. Students may be highly encouraged to take “elective” courses in areas in which they need skills. High schools that have double class periods may be long enough for naturalistic instruction in the community and provide opportunities for generalization of skills across settings. This type of “elective” can also be designed to provide specially designed group and individual instruction, as needed. More and more IEP teams are including “elective” classes on topics related to transition as part of the student’s Course of Study.

An approach, particularly common with students with ASD who have cognitive and/or language challenges, is to provide at least some instruction in a life skills or functional skills class. This approach generally provides direct small group or 1:1 instruction with skills embedded throughout the school day and in community settings.

For those who require more than 12 years to acquire the skills and knowledge for adult living, instruction may be continued until the age of 21. This may be particularly beneficial to hone skills for work, postsecondary school, and independent living. However, beginning the expanded core curriculum at this stage of the youth’s educational career would be too late to adequately prepare the individual for adulthood.

Extending the education beyond 12 years may also apply for those without cognitive or language challenges. For some students with ASD who are managing complex academic work, but need more instruction in functional and social skill needs, IEP teams have taken advantage of the extra time provided to students with disabilities to meet their functional and academic instructional needs. For instance, an IEP team might delay graduation for a student with ASD, who has advanced academic skills, but significant social and functional skill needs, and extend his high school career by one year (Virginia Department of Education, 2010).

What skills should I teach within each domain of the expanded core curriculum?

The need for instruction in specific skills is always based on both age appropriate transition assessment and the youth’s measurable postsecondary goals in training/education, employment and independent living. Annual goals for skills and a description of transition services that includes the supports and services, related services and community experiences are also part of the transition IEP.Units 3.1 – 3.8 cover the skill areas within the individual domains and how to determine what to teach within that domain. One of the most effective methods for identifying and prioritizing skills is environmental assessment.

Environmental assessment

To reasonably ensure that youth and young adults with ASD can meet their postsecondary goals for training/education, employment and independent living, educators must have an understanding of what is occurring in desired future environments and what skills the youth needs to participate effectively. There is a limited amount of time and a limited number of annual goals and skills that can be addressed at any one time, so skills that are the highest priority for the youth to learn must be judiciously identified. An environmental assessment, also known as ecological assessment, provides information for the team to utilize in making decisions about annual goals and transition services.

Environmental assessment is a careful and systematic approach to identifying necessary skills. Five critical components make up an environmental assessment:

- Identification of behaviors or skills being performed through an environmental inventory

- Identification of natural cues that let others know what to do

- Identification of conditions in the environment

- Identification of how or in what period a skill is typically performed

- Assessment of the youth with ASD’s ability to perform the skills identified in the environmental inventory

An environmental inventory, also know as ecological inventory, is a format designed to delineate how capable adults perform an activity in a given environment. Environmental assessment focuses on the specific environments where the youth will spend time in the future, such as primary home, community, and/or recreational environments, that are inherent in a youth’s postsecondary goals and transition services. Since there may not be time to assess all environments, the team may need to prioritize which environments to assess.

To complete an environmental inventory the evaluator observes and records the sequence of skills in the activity or task. Expectations in the natural environment are determined through watching what proficient people are doing. Environmental assessment enables educators to look at both the skill being performed and the related skills naturally integrated in the activity. It is used to discover related skills for competence in the activity, such as communication, social, organization, problem solving and self-regulation. In addition to identifying skills, it includes 1) identifying what natural cues guide individuals in performing the steps, 2) determining conditions, such as social demands, organization of the space and materials, the level of sensory stimulation, expectations in the environment, and receptivity of the people and environment to change, and 3) finding out what is typically done and how long it usually takes to do it.

After the environmental inventory is finished, the information is organized in a sequential manner and the youth with ASD is observed in that environment to see if and how he performs each step delineated in the environmental inventory. He may be able to say what he should do or be able to use the skills or set of skills elsewhere, but a strength of environmental assessment is that it demonstrates what the youth does in a priority environment where he will need to use them.

Once the environmental assessment is completed, it is used as the foundation for developing meaningful goals and transition services, such as instruction and supports. Comparing the environmental inventory and the youth’s performance will help identify any discrepancy from essential skills or behaviors in that environment. Decisions can then be made on priority skills that will have the greatest impact on a youth meeting his postsecondary goals.

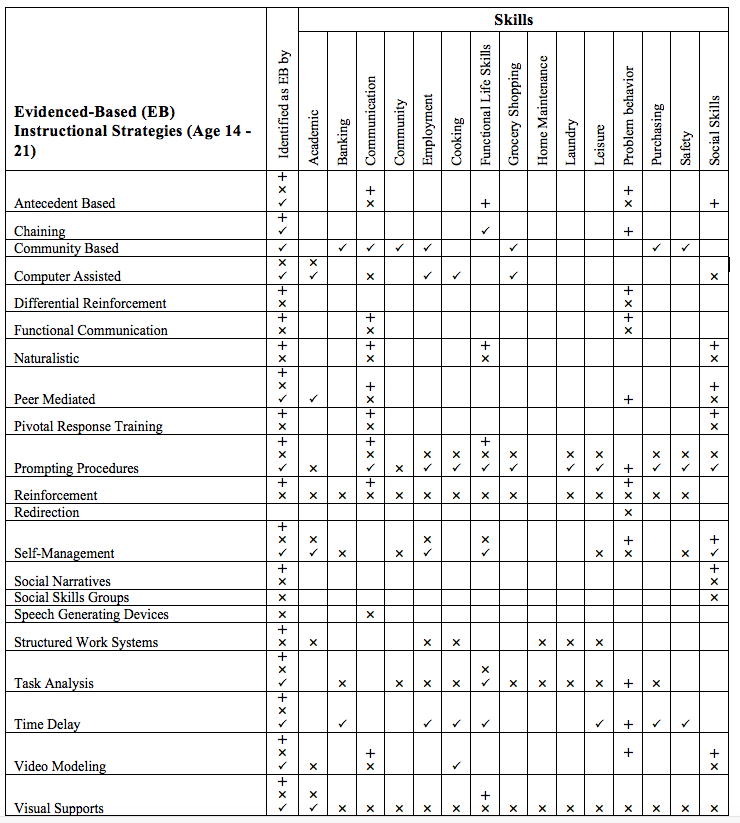

What evidence-based practices can be used to teach skills in the expanded core curriculum?

Students with ASD require individualized instruction and support throughout their transition from school to adult life that uses best practices for youth with ASD (Barnhill, 2007; Schall and Wehman, 2009; Seltzer et al., 2004; Simpson, 2005; Wolfe, 2005). There are a growing number of published studies documenting the efficacy of instructional strategies for youth with ASD that can be used to teach the domains of the expanded core curriculum. Both the National Professional Development Center (NPDC) on Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) and the National Standards Project (NSP) of the National Autism Center (NAC) reviewed literature and applied rigorous criteria to establish evidence-based practices (EBP) for students with ASD between the ages of birth and 22 years. The criteria used by each organization differed slightly, which resulted in a few strategies that were determined to be evidence-based by NPDC or ASD, but an “emerging” practice with some evidence of effectiveness, requiring more rigorous research, by NAC. For example, Social Skills Training Groups, Speech Generating Devices and Computer-Aided Instruction were initially identified as evidence-based by NPDC on ASD and an “emerging” practice by NAC. (Note: NAC Phase 2 results were published in 2015)A major challenge in determining evidence-based practice is the limitations of the current research and differing criteria. The criteria used by the NPDC on ASD can be found in the Evidence-Based Practices section of their website. The criteria used by the National Standards Project can be found beginning on page 10 of the National Standards Report.

There are, also, a growing number of studies that show the effectiveness of instructional strategies for various skills associated with successful transition. The National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC) reviewed literature and applied rigorous criteria to establish evidence-based practices that were designed to teach youth with disabilities specific transition-related skills (EBP: Student Development). In addition, NSTTAC reviewed rigorous correlational research in secondary transition to identify evidence-based predictors that are correlated with improved post-school outcomes in education, employment, and/or independent living (Predictors).

Some evidenced based practices are effective in teaching a variety of skills, while others have been shown to be effective with teaching specific skills. EBP for Youth with ASD compares the strategies that are considered evidence-based by NPDC on ASD, NAC and NSTTAC for students aged 14 – 21 for specific transition-related skills. Definitions for these evidenced-based practices can be found in the Glossary. Many of these strategies are often supplemented by additional strategies, such as prompting, reinforcement, and visual supports.

Educators may not know how to implement all the evidenced based practices. Fortunately, there are sites that provide enough information to get you started. NPDC on ASD provides EPB Briefs that include step-by-step directions for implementation and checklists. The following evidenced based practices on their site are effective in instruction of functional life skills for youth with ASD.

- Antecedent-Based Interventions (ABI)

- Computer-Aided Instruction

- Differential Reinforcement

- Functional Behavior Assessment

- Functional Communication Training

- Naturalistic Intervention

- Peer-Mediated Intervention

- Prompting

- Reinforcement

- Response Interruption/Redirection

- Self-Management

- Social Narratives

- Speech Generating Devices/VOCA

- Structured Work Systems

- Task Analysis

- Time Delay

- Video Modeling

- Visual Supports

Additional resources for learning how to implement these evidence-based instructional strategies include the Autism Focused Intervention Resources and Modules (AFIRM) and Autism Internet Modules (AIM). Both provide free training modules, some specifically tailored to educators and clinicians preparing youth and young adults with ASD to function successfully in the workplace and in the community.

You may find that some of the aforementioned modules emphasize tools or strategies that are not included in lists of evidenced-based practices from NAC, NPDC on NSTTAC. That is because some approaches do not have sufficient support to be desgnated as evidence-based and have been instead determined to be “emerging” or "promising" practices with some evidence of effectiveness, but require more rigorous research to determine their efficacy. Finally, some modules focus on tools for designing a comprehensive plan for our students with ASD. For example, The Ziggurat Model is not an intervention. Rather, it is a planning process that assists teams in selecting evidence-based practices to address goals identified via assessment.

What approaches are important for teaching youth with ASD?

There are a number of key concepts that lead to improve learning of youth with ASD. Instruction must be intensive and provide sufficient opportunities for practice, generalization, and maintenance of learned skills (Chin & Bernard-Opitz, 2000). Some critical approaches are:

- Train generalization of skills

- Teach in the environment where the skill will be used

- Provide and teach to use multiple supports, particularly visual supports

- Use evidence-based and “emerging” instructional strategies

- Embed instruction of related skills into instruction of tasks and activities

- Provide frequent opportunities for ongoing practice

- Teach thinking about the skill

Train generalization of skills

Youth with ASD have difficulty generalizing skills from one setting to another, therefore instruction and the opportunity to practice skill(s) across settings, people, and materials is critical. Given the difficulty that students with ASD have generalizing skills from one setting to another, providing inclusive experiences in real environments is a very effective educational strategy. The goal is that a learned behavior will be repeated correctly in a new situation, or a learned skill or principle will be applied in a new situation. In effect, generalization is the most critical concept in teaching. However effective instruction might otherwise be, if a learned behavior or skill does not transfer to relevant functional application contexts and/or is not maintained over time, then the instruction has failed.

Teach in the environment where the skill will be used

Because of the difficulty that many individuals with ASD experience when attempting to generalize skills from one setting to another, it is most effective to teach them in the environment in which they will use the skill. Community-based training experiences appear to be the most functional regardless of the youth’s severity of ASD. Additionally, it is a predictor of positive transition outcomes (National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center, 2009). The skills within the domains of the expanded core curriculum will be used at home, work, education/training, or in community settings, by necessity, instruction frequently needs to take place outside of the school setting.

Provide and teach to use multiple supports, particularly visual supports

Before beginning instruction, be sure that supports and structure are in place. Instruction and activities must include a carefully planned environment that is predictable, organized and structured to support youth with ASD. Youth with ASD do not necessarily know how to use supports when they are first presented to them, so they often need to be taught how to use them with lots of opportunity to practice until they are able to independently use the support structure.

Use evidence-based and “emerging” instructional strategies

Youth with ASD require individualized instruction throughout their transition from school to adult life that uses best practices for youth with ASD (Barnhill, 2007; Schall and Wehman, 2009; Seltzer et al., 2004; Simpson, 2005; Wolfe, 2005). Schools are required to use evidenced-based practice. The previous question, “What evidence-based practices can be used to teach skills in the expanded core curriculum?” contains specific information on evidence-based practices that are useful in teaching skills within the domains of the expanded core curriculum for youth with ASD.

Embed instruction of related skills into instruction of tasks and activities

Research has shown that embedded instruction leads to the acquisition and maintenance of the target skills (Johnson & McDonnell, 2004; Johnson, McDonnell, Holzwarth, & Hunter, 2004; Reisen, McDonnell, Johnson, Polychronis, & Jameson, 2003; Wolery et al., 1997). Because related skills are often more difficult for a youth with ASD to learn than the steps for an activity, task or routine, these skills need to be embedded into instruction of functional skills. Related skills may include communication, social interaction, organization, problem solving and self-regulation skills that are necessary to be successful in a routine, activity or task.

Provide frequent opportunities for ongoing practice

Youth with ASD need opportunities to demonstrate, practice, and be reinforced for the skill or behavior frequently and across a variety of settings. Depending on the complexity of the skill being taught and the degree of challenge for the individual, the skills need to be taught very gradually and potentially over a long time until the youth with ASD uses the skill independently or to the established criteria.

Teach thinking about the skill

Youth with ASD need to understand the purpose and meaning of instruction and eventually have their own personal plan for how to use their skills. The purpose and importance of instruction needs to be explicitly explained in a manner that the youth can understand.

Appendix 3A

Online and Other Resources

- Autism Spectrum Disorder

- Program Planning

- Evidenced-Based Practice

- Online and Other Training

- Practical Books Available on Loan

The resources listed are available at no cost online. While terminology sometimes differs from Website to Website, basic concepts are the same. Information is either, specific to youth and young adults with ASD or can be adapted for the individual need of the student.

AUTISM SPECTRUM DISORDER

Autism: Reaching for a Brighter Future, Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI) - These guidelines offer comprehensive information on ASD.

Autism Society - This site provides information about autism, symptoms, education and treatment options, tips on how families can learn to cope together and links to websites that provide useful information on how to get services.

Autism Spectrum Disorders and the Transition to Adulthood, Virginia Department of Education, Office of Special Education and Student Services - This is a comprehensive guide to ASD and transition.

Behaviors That May Be Personal Challenges For A Student With An Autism Spectrum Disorder - This document provides forms, which are adapted from the Technical Assistance Manual on Autism for Kentucky Schools by Nancy Dalrymple and Lisa Ruble, provide checklists for what may be personal challenges for individuals with ASD.

Columbia Regional Program - This site offers information and resources for educators and parents on ASD, serves Multnomah, Clackamas, Hood River, and Wasco counties in Oregon

Indiana Resource Center for Autism (IRCA), Indiana Institute on Disability and Community - This site provides information and research about ASD.

Life Journey Through Autism: A Guide for Transition to Adulthood, Organization for Autism Research (OAR) - This publication provides an overview of the transition-to-adulthood process.

OASIS @ MAAP - This site provides articles, educational resources, links to local, national and international support groups, sources of professional help and more.

Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI) - This site provides information and resources about ASD and transition.

Recognizing Autism, Autism Internet Modules - This site offers modules about Recognizing Autism. The modules include Assessment for Identification, Restricted Patterns of Behavior, Interests, and Activities, and Sensory Differences. (This site requires you to login to gain access to the modules. Sign up is free.)

Transition to Adulthood Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD), Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI) - This site offers several comprehensive guides for parents and professionals on the process of transition to adulthood for individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD).

Program Planning

Comprehensive Autism Planning System part 1 - These handouts on CAPS provide information on reinforcement, sensory, strategies, social skills/communication, data collection and generalization.

Global Intervention Plan: Guide to Establishing Priorities - This planning sheet, although designed specifically to use with the UCC assessment, provides an outline of areas to consider in overall program planning for students with ASD.

Modified Comprehensive Autism Planning Systems (M-CAPS) for Middle ... - This is a blank form for the Modified Comprehensive Autism Planning Systems, which was developed for students with ASD in secondary school.

Recommendations of the Redesign of ASD Education Services Subcommittee and Interagency Transition Services Subcommittee, Oregon Commission on Autism Spectrum - This report provides the recommendations, including The Expanded Core Curriculum, from the Redesign of ASD Education Services Subcommittee.

Sustainable change in quality of life for individuals with ASD: Using a comprehensive planning process - This article includes comprehensive information on the Ziggurat Model and Comprehensive Autism Planning System

Evidenced-Based Practice

Evidence-Based Practice and Autism in the Schools, National Center on Autism - This downloadable manual contains good descriptions of a number of supports in Chapter 2, including antecedent and behavioral packages, video modeling and schedules.

Evidence-Based Secondary Transition Practices, National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Program - This site offers information on evidence-based practices and predictors, practice descriptions, and other resources.

Organization for Autism Research (OAR) - This site offers evidence-based information about ASD.

Sustainable change in quality of life for individuals with ASD: Using a comprehensive planning process - This article contains a chart comparing evidence-based practice from Medicare and two major organizations on ASD.

Online and Other Training

Autism Internet Modules - These free training modules contain Introduction, Pre-and Post Assessment, Overview, Module Objectives, Definition(s), Developing, Summary Evidence Base, Frequently Asked Questions, References, Step-by-Step Instructions, Implementation Checklists, Documents, Discussion Questions and Activities for each strategy. To log on first create a free user account.

National Professional Development Center on ASD - The National Professional Development Center on ASD has developed Evidence-based practice (EBP) briefs for a number for the evidence-based strategies that they have identified. Most contain: Brief, Overview, Evidence Base Steps, Checklist, and Data collection form

Oregon Technical Assistance Corporation (OTAC) - OTAC promotes full participation in community life for individuals with disabilities, seniors and their families through the delivery of training, technical assistance and related services.

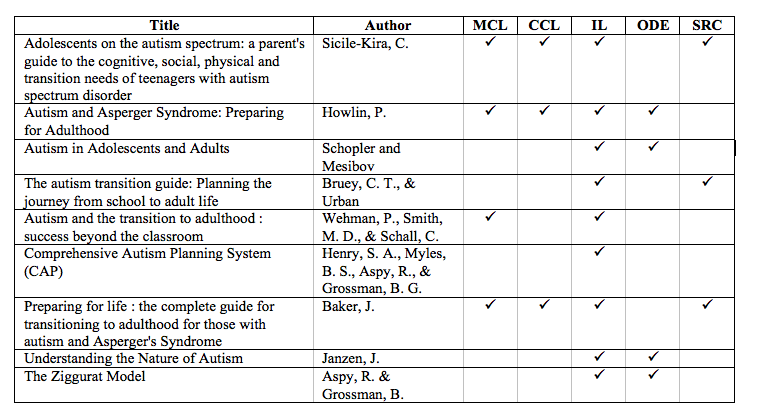

Practical Books Available on Loan

Many libraries, including the ones below, have books and other material on youth with ASD to loan.

Multnomah County Library (MCL)

Reference Line: 503.988.5234

Clackamas County Libraries (CCL)

Library Information Network: 503.723.4888

SRC: Jean Baton Swindells Resource Center for Children and Families

503.215.2429

Below is a list of books on youth with ASD that can be borrowed from the sources indicated. Check with your library for additional titles.

Books

Appendix 3B

Evidenced-Based Practice

Evidenced-Based Instructional Strategies for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Code: + National Autism Center (NAC); X National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders (NPDC); √ National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC)

Appendix 3C

Glossary of Terms

Antecedent based interventions. Modifying the environment, antecedents, or setting events to prevent the need for challenging behavior.

Augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Devices to help youth communicate and interact within their environment. This is accomplished through the use of switches, buttons, pictures, and many other adaptive devices.

Backward chaining. Breaking down the steps of a task and teaching them in reverse order.

Chaining. Instructional procedure involving reinforcing a Series of related behaviors, each of which provides the cue for the next (e.g hand washing, tooth brushing and showering).

Communication skills. Skills to communicate intentionally and effectively, including expressive and receptive skills, for school, home, work and the community. See Unit 3.1 for detailed information and resources for communication.

Community-based instruction. Regular and systematic instruction in meaningful, functional, age-appropriate skills in integrated community settings, using naturally occurring materials and situations, designed to help the student to acquire and generalize life-skills that enhance his opportunities for meaningful experiences and relationships within the general community.

Computer-aided instruction. Use of a computer to teach communication or academic skills. There are some programs currently being used to teach social skills as well.

Constant time delay. Fixed amount of time is always used between the instruction and the prompt.

Differential Reinforcement Integrated into Self Management Plans. Providing positive reinforcement for the absence or lower rate of a problem behavior.

Ecological assessment. Assessments that look at individual needs and interests in all current and future environments.

Education and training. Enrollment in (a) community or technical college (2-year program), (b) college/university (4-year program), (c) compensatory education program, (d) a high school completion document or certificate class (Adult Basic Education, General Education Development), (e) short-term education or employment training program (Job Corps, Vocational Rehabilitation), or (f) vocational technical school, which is less than a two year program. Education/training can also include on-the-job training or more informal training efforts for those students who are not enrolled in a formal education or training program (NSTTAC, p. 3).

Embedded instruction. Skills taught in the context of naturally occurring activities and transitions.

Employment skills. Knowledge and skills that enable youth with ASD to move toward working as an adult, including exploring and expressing preferences about work roles; assuming work responsibilities at home, school and community; understanding concepts of reward for work; participating in community based job experiences; and learning about jobs and adult work roles at a developmentally appropriate level. See Unit 3.6 for detailed information and resources for preparation for employment.

Executive function. A neuropsychological concept referring to the cognitive processes required to plan and direct activities, including task initiation and follow-through, working memory, sustained attention, performance monitoring, inhibition of impulses, and goal-directed persistence. See Unit 3.3 for detailed information and resources for executive function.

Forward chaining. Chaining procedure that begins with the first element in the chain and progresses to the last element.

Functional communication training. Replacing a problem behavior with a communication behavior.

Generalization. Learned behavior repeated correctly in a new situation, or a learned skill or principle applied in a new situation.

Independent and Community Living Skills. Skills needed to function as independently as possible at school, home, work and the community, such as personal grooming, time management, cooking, cleaning, clothing care, and money management. See Unit 3.8 for detailed information and resources for skills for independent living and community participation.

Instruction. Component of a transition program that the student needs to receive in specific areas to complete needed courses, succeed in the general curriculum and gain needed skills.

Natural cue. Naturally occurring cue that individuals rely on to let them know what they need to do.

Naturalistic intervention. Providing cues, prompts, and instruction in natural environments to elicit and reinforce communication and social behaviors

Organization. The ability and skills to create and maintain systems to keep track of information or materials. See Unit 3.3 for detailed information and resources for organization.

Peer mediated instruction. Teaching peers without disabilities to interact with and cue positive social behavior.

Pivotal response training. Applying the principles of applied behavior analysis to natural environments to teach pivotal behaviors including motivation, responding to multiple cues, social interaction, social communication, self-management, and self-initiation.

Postsecondary Education. Any education beyond the high school level. Examples include vocational schools, community colleges, undergraduate and graduate institutions.

Progressive time delay. Time between giving the instruction and giving a prompt is gradually increased.

Prompting Procedures. Verbal, gestural, physical, model, and visual prompts and prompting systems including least to most prompts, simultaneous prompts, and graduated guidance.

Reinforcement. Strengthening any behavior by providing a consequence that increases the likelihood that the behavior will occur again. Includes positive reinforcement, tokens, point systems, graduated reinforcement systems.

Related skills. Communication, social interaction, organization, problem solving and self-regulation skills that are necessary to be successful in a routine, activity or task.

Response Interruption/ Redirection. Providing another activity that appears to serve the same function as a problem behavior, e.g.: Offering popcorn in place of eating a pencil (pica: the persistent eating of substances such as dirt or paint that have no nutritional value.).

Self-Advocacy. The process of obtaining needed services for oneself.

Self-Determination. Skills to enable students to become effective advocates for themselves based on their own needs and goals. See Unit 3.5 for detailed information and resources for self-determination.

Self-Management. A wide array of interventions to increase appropriate behaviors and decrease problem behaviors for learners across the spectrum, including social conversation, sharing, giving compliments, anger management, habit reversal, etc.

Sensory regulation. The ability to attain, maintain, and change arousal levels appropriately for a task or situation.

Sensory Self-Regulation. Skills to self-monitor and self regulate one’s own sensory state. See Unit 3.4 for detailed information and resources for sensory self-regulation.

Social Narratives. A written intervention where social situations and responses are described in detail. Social Stories™ developed by Carol Gray, are included in this category.

Social Skills Groups. Up to eight individuals with ASD practice social skills and social interactions in a group with an adult facilitator.

Social Skills. Skills needed to respond appropriately and participate actively in social situations at school, home, work and the community. These may include skills and concepts, such as initiating, maintaining, and ending conversations, social understanding and managing emotions. See Unit 3.2 for detailed information and resources for social skills.

Speech Generating Devices (Voice Output Communication Assistance, VOCA). An electronic device that has small to large screens where a picture indicates what will be said when pressed.

Stimulus Control. Using reinforcement to teach a person to perform a certain behavior under very specific stimuli.

Structured Work Systems. Designing the environment so that work is visually displayed and expectations for completion are visually presented as well.

Task Analysis. Teaching skills with many steps a few steps at a time with reinforcement following each step.

Time delay. Prompt fading strategy, in which a delay is inserted between giving an instruction and prompting.

Training and Education Skills. Knowledge and skills that enable youth with ASD to move toward postsecondary training and education. See Unit 3.7 for detailed information and resources for preparation for postsecondary training and/or education.

Video Modeling. Using video to show the correct way of responding to a variety of social situations.

Visual Support. Providing an array of information in visual formats including the daily schedule and steps to complete a task, social behaviors, communication supports, how to transition between activities.

Copyright © 2016 Columbia Regional Program