-

Preparing Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder for Adulthood A Transition Toolkit for Educators

UNIT 3.1: Communication

Key Questions

- What are the communication challenges for youth with ASD?

- Why is communication intervention needed?

- What communication skills are needed for successful functioning as an adult?

- What does 'behavior is communication' mean?

- How do I know what communication skills to teach?

- How do I teach communication skills?

- How should supervisors and co-workers communicate with employees with ASD?

Appendices

by Brad Hendershott

Communication for Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder

Although most educators know that communication is important for youth with ASD, they may not know how and where to focus instruction. The information and practical resources in this unit of The Expanded Core Curriculum are designed to better enable help educational staff to instruction. Please be aware that communication and social skills for youth with ASD are not mutually.

This is a resource for you and is designed so that you can return to sections of the unit, as you need more information or tools. You do not need to read this unit from beginning to end or in order. Feel free to print this unit for ease of reading or as an accessible reference. Links to questions, appendices and online resources are provided so that you can go directly to what is most relevant to you at the time.

What are the communication challenges for youth with ASD?

Communication refers to all the ways in which we send and receive information. We often think of spoken language first when talking about communication. Yet, when we speak, only a portion of the meaning is carried in the words themselves. Important information is embedded within variations of intonation, rhythm, volume, and even the stress we place on sounds and words. We send and receive information via a variety of non-verbal means as well, including gesture, facial expression, eye contact, and body posture. This is all important to point out because individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) are often said to experience global impairments in communication. (Shriberg, Paul, McSweeny, Klin, Cohen, & Volkmar, 2001).

Communication challenges are a central feature of ASD and occur along a continuum. The severity of expressive language impairments range from being functionally non-verbal (e.g., fifteen or fewer spontaneous words) to being highly verbal with idiosyncratic features such as speaking with an unusual rate, rhythm, and volume or sounding overly pedantic or formal. Ironically, many high functioning individuals produce advanced-sounding language when talking about preferred topics thus masking significant underlying gaps with comprehension. Receptive challenges range from those who understand only a handful of spoken words or phrases to those who possess tremendous vocabularies but struggle with understanding non-literal language (e.g. idioms, figures of speech, irony, sarcasm) and indirect communication. There are messages, which neurotypical individuals easy understand, but are too subtle or rely upon intact social cognition to be understood by even highly intelligent youth with ASD.

Why is communication intervention needed?

Mesibov stated, ‘When children with autism become adolescents, they must be able to communicate on some level if they are to function outside of highly structured home and classroom environments’ (2007, p. 6). Youth with ASD will often have had years of intervention to develop communication skills. As students age, the importance of directly teaching communication skills does not diminish. Transition services must prepare youth for adult life, and communication skills should be targeted which will be needed for employment, postsecondary education, independent living, and community participation.

For a youth or young adult who has not developed functional speech, it is critical that some system of aided or unaided augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) system is in place to provide an opportunity to develop an independent means of expressing at least basic communicative functions such as requesting, responding to others, commenting, and requesting information. Certainly more functions may be targeted such as expressing feelings, making pro-social comments, and engaging in conversational exchanges. If a youth without functional speech lacks such a system, it is never too late to pursue putting a system in place. System refers to any combination of aided AAC (requiring a device or tool such as a voice output device) or unaided AAC (does not refer to a specific device or tool such as manual signs, gestures, etc.). In a 2012 meta-analysis, Ganz and colleagues found that AAC approaches - particularly speech-generating devices (SGDs) and the Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS) - produced positive effects in increasing communication skills for individuals with ASD.

Counter to some beliefs, there are no prerequisite skills, which must be in place prior to implementing AAC. Another commonly held myth is that introducing AAC will impede the use and development of speech. Research has consistently found that AAC interventions promote speech development (Mirenda & Iancono, 2009). What happens when a youth or young adult with ASD lacks a reliable system of communication? Negative outcomes include:

- Persistent and undue levels of dependence upon adult/caregiver support.

- Elevated risk for challenging or destructive behaviors as a result of not being able to communicate. May communicate via behaviors, and then learn that it is only through these behaviors that the student gets their wants and needs met.

- Adverse impact on quality of life - establishing and maintaining relationships/friendships, getting and keeping a job, navigating the social world.

- Reduced opportunities for cognitive, language, and academic development.

Even for youth with ASD who are verbally fluent, communication deficits negatively impact the ability to establish and maintain relationships as well as obtain and keep a job. A youth with ASD may fail to interpret the facial expression and body posture of a co-worker who is annoyed or angry with them, giving the co-worker the impression that the youth with ASD is indifferent, uncaring, or rude when in reality the individual with ASD lacked the skills to attend to and/or interpret what was being communicated. Or a supervisor might make an indirect and vague request such as “John, I’d like to see everyone help clear out the back room.” What the supervisor is really saying is, “John, go into the back room and move those five boxes into storage.” The supervisor is also implying that the job should not fall entirely on just one or two people. John, who has ASD, interprets the comments literally and misses the implied direction. Further, due to the ASD, John is not thinking about how his behavior may be perceived by others. He is also unaware of unspoken social expectations within that particular context. So John misses the message and does not help with the move; his supervisor and/or co-workers may easily misinterpret John’s behavior, thinking that he is lazy, uncaring, or has poor listening skills. In yet another work situation, a youth with ASD may lack the expressive communication skills to ask for help when needed, or ask for additional materials to complete a job task; both essential communication skills for nearly all work environments.

What communication skills are needed for successful functioning as an adult?

For students individuals with autism who have mild to severe cognitive challenges, Mesibov identified minimal communicative abilities necessary for successful functioning in employment and community settings. These include, ‘the ability to communicate basic needs, comprehension of instructions and gestures, and response to commands and prohibitions.’ (2007, p. 6). Important functional communication skills for youth with ASD include:

- Spontaneously communicating basic needs (i.e. hunger, thirst, fatigue, pain, sick, warm, cold, need a break, need to use toilet) with clear gestures, words, or other means (e.g. AAC) without prompts.

- Responds to questions from others when asked about present state (e.g. “Are you finished?”, “Do you want a drink”).

- Understanding of basic semantic concepts encountered during a typical day: names of people, objects, actions, locations (e.g. “in the kitchen”), time concepts (e.g. tomorrow, next week, later), reasons and causes, and sequences (e.g. “First we’ll do the recycling, then we’ll move the boxes”).

- Expressively uses semantic concepts (see above) in daily conversation.

- Reads and understands written signs (e.g. men, women, walk, exit, do not enter).

- Uses the telephone to answer and make calls, understanding and using conventional phone language and expected protocol.

- Communicates need for assistance, materials, or information.

- Understands and carries out familiar, single-step instructions without repetition or guidance.

- Understands and complies with prohibitions, such as being told to not do something or to stop doing something.

- Follows instructions with are conditional and require decision-making (e.g. “If the copier stops working, go tell David.”).

- Follows delayed instructions (e.g. “When the timer rings, put all the pens in the box”)

- Understands and responds to basic gestures (e.g. wave, quiet “sh”, come here).

- Follows pointing gestures of others to obtain objects or information.

- Uses gestures (e.g. pointing or holds out hand for an object) to request a desired object.

- Rejects with gestures or words (e.g. shakes head, verbally says “no”).

- When told to stop, ceases and action without major signs of agitation.

- Responds to praise or approval from a supervisor/authority and continues with activity/action.

- Provides emergency information when asked in verbal, written, or some other form (e.g. name, address, phone number)

- Follows instructions in an emergency.

- Displays generally positive affect (via facial expression, body posture, etc.) at generally appropriate times.

- Follows pictorial or written instructions.

Some youth with ASD demonstrate these communication skills in more conventional ways, while others use alternative means.

What does ‘behavior is communication’ mean?

Students with ASD who lack reliable functional communication or whose means of communication fails them at times (such as when stressed or overwhelmed) may communicate through disruptive or challenging behavior. In other words, their behavior is communicative. For example, a student may crawl under a desk, which communicates, “I’m overwhelmed and scared. I need out of here!”. The concept of “behavior as communication” is critically important for those of us who support youth with ASD. It may be through a student’s difficult or challenging behavior that they are, intentionally or unintentionally, communicating their needs. Since this is often the case, we must: 1) attempt to determine the function of the behavior, and 2) identify and teach an alternative; an appropriate communicative behavior which allows the youth to get their needs met. Even our highest functioning and verbally fluent students can communicate through behavior in times of elevated anxiety, confusion, and frustration.

Some of our most impacted students with ASD, those with “classic” autism, do not appear to grasp the “power of communication”. They do not know that they can send a message to another person to change their thinking and affect their behavior. An individual who does not understand the power of communication will likely turn to non-conventional means of getting their needs and wants met. They may lead another person by hand to a desired object or activity, or take matters into their own hands by simply going for the desired item or activity rather than asking someone. To observers, the youth with ASD may appear incredibly impulsive or disruptive when, seemingly without warning, he goes for a desired item or activity (or moves to avoid a non-preferred item or activity). An observer unfamiliar with ASD may wonder why the youth doesn’t simply make a request or tell another person what they need. If those efforts to obtain or avoid fail and are then compounded by the lack of a reliable means of communication, the youth with ASD may experience peak levels of frustration.

In “crisis mode”, some youth internalize by “shutting down”, becoming unresponsive to others, crawling under a desk, running away, and so forth. Other youth may externalize, engaging in disruptive or destructive behaviors. In all cases, it is most productive to view these challenges as resulting from skill deficits that require teaching and support, rather than viewing incidents as “bad behavior” which can be extinguished with a disciplinary response. The article, The Cycle of Tantrums, Rage, and Meltdowns in Children and Youth with Asperger Syndrome, High-Functioning Autism, and Related Disabilities (Smith-Myles and Hubbard, 2005), provides an excellent framework for understanding and responding to these moments of peak frustration. Sometimes supports developed for one student with ASD can be modified to meet the needs of other youth, if the individual differences are taken into account. However, never assume that generic supports will suit all youth with ASD. Educators who just use a readymade support with a student with ASD without careful consideration of his needs may very quickly discover that this approach can exacerbate a situation rather than help.

How do I know what communication skills to teach?

Most youth with ASD will have had assessment of functional communication as part of their initial eligibility for special education. Most have also had a great deal of assessment of communication and communication intervention over the years. All of this information is important to consider. However, it is essential to assess what the youth with ASD can currently do related to communication along with the skills he will need to reasonably enable him to reach his postsecondary goals. Those postsecondary goals for employment, secondary education, and independent living should drive assessment. Assessment should identify which functional communication skills will be needed in those post-school settings. Consider how much time in school remains for the youth with ASD and prioritize critical skills. When working on communication with youth with ASD, educators should ask themselves “Do I know what my student’s postsecondary goals are? Is what I am teaching connected to those goals? Is what I am teaching preparing the student for adult life?” We should be asking these questions by the time youth with ASD reaches age 13, if not sooner.

Ideally, a Speech-Language Pathologist (SLP) should be involved to conduct (or recently have conducted) an assessment of functional receptive and expressive communication skills. For more impacted individuals, this often includes determining the level of linguistic development, and gathering an inventory of communication forms (e.g. verbal, gestural) and functions (e.g. request, protest, comment). For students who are functionally non-verbal and appear to require some type of AAC intervention, it is important to conduct some assessment of level of representation. That is, assessment may be conducted to help determine which types of symbols (words, line drawings, photographs, objects) an individual with autism understands as representational of the ‘real thing’. It may be tempting to think of a line-drawing of an apple and assume that everyone understands that the drawing represents an apple. However, for some highly communication impacted youth with ASD, the image may carry no symbolic meaning whatsoever. For those “who function at the earliest stages of communication and who use any form of communication”, The Communication Matrix (Rowland, 2011) is a valuable assessment. A well regarded process for matching individuals in need of AAC with appropriate tools and strategies is SETT (Student Environment Tools Tasks).

For verbal youth with ASD and those with average or above cognitive ability, communication assessment may examine receptive skills such as the ability to understand non-literal forms of language, interpret indirect forms of communication, determine meaning in context (i.e. main idea or ‘big picture’), and comprehend written and spoken information to answer both literal questions (e.g. what?, when?, where?) and increasingly abstract questions (e.g. why? how?). Examination of expressive communication considers vocal characteristics including prosody (i.e. rising and falling intonation to connote meaning) volume and use of advanced-sounding vocabulary (which may mask overall weakness in general knowledge). Expressively, youth with Asperger Syndrome (AS) may be tangential. Their comments may lack an overall coherence. They may not provide adequate background or context for their comments, confusing listeners. They may not ‘filter’ themselves, so thoughts which others might keep to themselves, the youth with AS will say, which others might mistake as tactlessness or being rude. Additionally, some individuals with AS are known for their verbosity, talking at length about a preferred topic without necessarily reaching a clear conclusion and without showing adequate regard for the level of interest of their conversational partners (Volkmar et al, 2005).

As previously stated, we should target communication skills, which will help youth with ASD reach post secondary goals. This may involve addressing skill deficits which undermine social integration and acceptance by peers.

Informal rating tools are a valuable way to inventory communication skills in a youth’s repertoire and identify which skills are needed in postsecondary education, employment, and independent living settings. Previously described in this unit, the TEACCH Transition Assessment Profile is one such tool. Rubrics for Transition (Wessels, 2004) is an assessment which includes task analyses for important real-word communication skills such as “Answering the Telephone” and breaks the skill into sub-skills including “Answers the phone within three rings”, “makes appropriate greeting”, “states who is speaking”, and so forth. Both tools are commercially available.

An environmental or situational assessment can be conducted to identify which specific receptive and expressive communication skills are needed for a specific work, living, or community setting or activity. Based upon what is already known about the student, skills to teach may be identified to help the student become ready for the environment. In addition, supports (accommodations and modifications) should concurrently be identified to ensure the environment is ready for the student (Aspy & Grossman, 2007).

How do I teach communication skills?

In our efforts to improve the communication skills of our students, we aim to prepare youth with ASD to move from school to adult life. Therefore, targeting functionality is critically important. Marci Hammel, an experienced autism specialist and program director for Autistic Community Activity Program (ACAP), provides examples of communication interventions, which have been employed to improve a youth’s ability to navigate the real world with as much independence as possible. By the time students reach high school, less emphasis should be placed upon remediating underlying skill deficits. Instead, focus should be placed on compensatory communication strategies.

For example, communicating a needed bus stop to a driver requires fluent, integrated use of a variety of skills such as approaching the driver, gaining the drivers attention, verbally communicating the needed stop, interpreting the drivers response, and so forth. Rather than teaching each sub-skill, the youth with ASD was provided with a card that said ‘My stop is 5th and Morrison’ which he was trained to show to the driver at the time of boarding the bus.

Communication exchanges in the community happen quickly; students need strategies, which are functional and efficient. Another example involves preparing a student to independently purchase a ticket to a movie. The youth with ASD was received instruction to ensure that he had prepared in advance what to say to the employee at the ticket booth. Knowing that the youth with ASD would quickly become overwhelmed by questions such as ‘How can I help you?’, ‘What do you want tickets for?’, ‘What time?’, the student received instruction to ensure that he had a pre-prepared verbal request, “I want two tickets to the 5 o’clock Harry Potter’. They then rehearsed and role-played making this verbal request before actually going to the movie theater to buy tickets. This way, the student was able to efficiently and completely communicate his request while simultaneously learning the skill of preparing messages in advance to avoid breakdowns. In the example above, a number of well established teaching strategies are employed including priming (previewing information or activities before actually engaging in the experience), role-play and rehearsal (practicing skills in advance before the actual situation in which they are needed), and scripts and script-fading (providing specific language for given social contexts).

As youth with ASD approach adulthood, it becomes increasingly important to move away from remediating underlying skill deficits in a manner, which is de-contextualized from real-world situations. Hammel stated, “I jump right into teaching the functional skill and/or compensatory strategy in the community setting where it will be needed on a day-to-day basis.” Sometimes referred to as ‘naturalistic intervention’, this approach provides instruction in natural environments along with prompts, cues, and reinforcement (i.e. social coaching) to teach and reinforce functional communication and social skills.

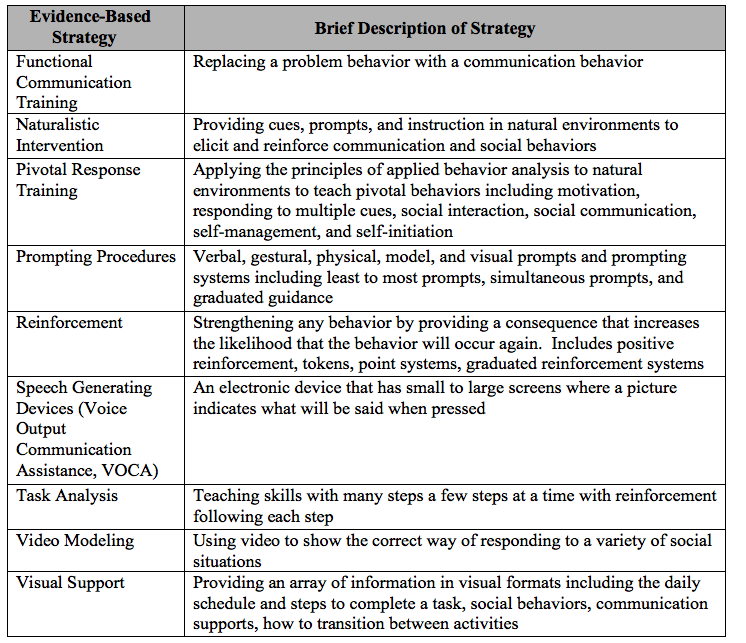

Evidence-based instructional strategies for youth with ASD, which are used to address communication skill development, are listed below.

Source: The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders, 2009

Rather than being taught in isolation, communication intervention for youth with ASD is often a component embedded within the teaching of functional routines or activities of daily life. For example, teaching an individual with ASD how to use the public bus system will include specific expressive communication skills such as requesting a specific stop or receptive communication skills such as reading signs to identify bus numbers/routes. Similarly, if an individual with ASD is learning to use a voice-output device, they may be taught to use the device in a real-world functional context. Most curricula designed for youth and young adults with ASD designed to support transition embeds communication instruction within domains such as employment skills, establishing and maintaining friendships, dealing with anxiety, and so forth (Baker, 2005).

How should supervisors and co-workers communicate with employees with ASD?

Communication skills are taught to prepare the youth with ASD for life after school. As we work to ensure our student with ASD is ready for his or her environment, we must also address the question, ‘How are we making the environment ready for the individual?” (Aspy & Grossman, 2007). Müller, Schuler, Burton & Yates (2003, p. 171-172) recommended specific communication supports for individuals with ASD in the workplace based upon extensive interviews with 18 individuals with autism. The following is an excerpt from their article, “Meeting the Vocational Support Needs of Individuals with Asperger Syndrome and Other Autism Spectrum Disabilities”.

Most participants stressed the importance of clear communication in the workplace. Because individuals with ASDs often have difficulty reading subtle communication cues, participants felt that it was particularly important that supervisors and co-workers be explicit in order to prevent miscommunication. One participant defined what clear communication meant to him:

"Say specifically in words – no hidden meaning stuff, no in-between-the-lines stuff…. And give good details. You’ve got to have details specifically. We’ve got to have things broken down. And when we have things broken down, then we do great."

A number of participants reported frustration at the fact that supervisors – perhaps out of a desire to be polite – often expressed themselves indirectly and expected participants to second-guess their real meanings. Guessing the intentions of others is extremely difficult for individuals with ASDs, and the majority of participants stressed their preference for direct, even blunt, communication. One woman, for instance, appreciated getting regular bi-monthly evaluations because it helped her understand what parts of her work she was doing well, and what parts of her work could be improved. Without explicit feedback, she reported having no idea "where [she] stood."

Participants also recommended that supervisors avoid giving vague or partial instructions regarding the performance of tasks. As one participant explained, "[People with ASDs] are going to need: First you do ‘a,’ then you do ‘b,’ then you do ‘c.’" Another participant suggested that – because prioritization does not come naturally for many individuals with ASDs – supervisors need to be explicit if certain tasks or components of tasks are more important than others:

"As far as prioritizing – if it’s more important to get this right than to get that right, tell them that. Because if you don’t tell them that, they’re going to be confused… Tell them that. Out loud. Totally spell it out."

Finally, several participants stressed that supervisors and co-workers should not just explain how to do things, but should also show individuals with ASDs how to do things. The more visual and hands on, the better. Furthermore, a number of participants recommended the use of written instructions as a supplement to oral instructions. In the words of one participant:

"I think writing out the instructions of what [the supervisor] wants done. That’s a biggie. If [he] writes it out – ‘this is what has to be done’ – you’re not wondering if there are any loose ends, which was a constant problem for me."

Significantly, according to several participants, a supervisor’s willingness to use multiple modes of communication – i.e., speech, writing, and modeling of behavior – often helped get the message across more clearly than simply using one mode or another.

Appendix 3.1A

Online and Other Resources

The resources listed are available at no cost online. While terminology sometimes differs from Website to Website, basic concepts are the same. Information is either, specific to youth and young adults with ASD or can be adapted for the individual need of the student.

ASD and Communication

Enhancing Communication using Environmental and Visual Supports and Strategies - This presentation outlines various ways to support communication for individuals with ASD using visual supports.

Hi Ho, Off to Work We Go, Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI) - This presentation provides examples for younger children. However, the research was also done with high school students and the examples can be adapted for that age group.

Vocational Supports for Individuals with Asperger Syndrome - This scholarly paper outlines strategies for improving vocational placement and job retention services for individuals with Asperger Syndrome and other autism spectrum disabilities. There is a section specifically on communication supports in the workplace.

Assessment

AAC SETT Planning Tool - This tool may be used to assess and plan for AAC interventions.

Assessing Students’ Needs for Assistive Technology (ASNAT) - Wisconsin Assistive Technology Initiative (WAIT). This is a resource manual for School District Teams from The Wisconsin Assistive Technology Initiative (WAIT).

The Communication Matrix - This assessment instrument is designed for individuals of all ages who function at the earliest stages of communication and who use any form of communication.

Vocational evaluation checklist - This is a vocational evaluation checklist with sections on communication and social interaction skills.

Instructional Material

AAC Curriculum Documents (2008), Special Education Technology - British Columbia. Two documents for those who are considering developing a course for students who use Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) systems. A curriculum outline and rubric are available.

Augmentative And Alternative Communication (AAC) Skills and Strategies - Special Education Technology - British Columbia. Theses scales are used to document student skills and student progress in a variety of settings and tasks.

Functional Communication Training - Texas Statewide Leadership for Autism . This document summarizes functional communication training, steps involved for implantation, and related research.

Project Spectrum - This site was created to give people with ASD the opportunity to express their creativity and develop a life skill using Google SketchUp 3D modeling software.

A Spectrum of Apps for Students on the Autism Spectrum - This is a list of apps for the iPod and iPad, including a section specifically on apps that support communication.

Supports for Communication

Boardmaker Share - This site offers thousands of freely downloadable visuals to support communication including pre-made language boards to fir in a variety of communication books and devices.

Challenges and Supports for Managing Vocational Issues for Individuals with Autism - This two-page document details challenges for individuals with ASD in vocational settings and recommended supports; includes section on Communication with employers and co-workers.

PictureSET - Special Educational Technology - British Columbia (SET-BC). This site offers a searchable database containing visual supports that can be downloaded and used by students for receptive and expressive communication across a variety of settings.

Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC)

Assistive Technology Supports for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder - Wisconsin Assistive Technology Initiative (WAIT). This manual is from The Wisconsin Assistive Technology Initiative (WAIT).

The Center for AAC and Autism - This site reviews Language Acquisition through Motor Planning (LAMP) as a strategy for helping nonverbal/minimally verbal individuals with ASD acquire independent means of expressive communication.

Communication Strategies for Children with Autism - J. M. Cafiero. This site provides ideas, research, information and support on supporting individuals with autism and complex communication needs.

The DynaVox InterAACt Language Framework - DynaVox. This site provides information about the DynaVox InterAACt language framework used on all DynaVox devices. It allows individuals with significant communication needs to successfully communicate, develop high-level language skills and express themselves, in everyday activities.”

Microsoft Publisher Manual for Visual Scenes - Kristy Weissling & David Beukelman. University of Nebraska, Lincoln. This manual provides instruction for creating low-tech visual scenes in Microsoft Publisher. Templates

Tangible Symbol Systems - This site describes tangible symbol systems, designed for individuals who are unable to communicate via spoken or written words and also struggle with understanding abstract symbol systems (i.e. Boardmaker symbols). Concrete, tangible symbols may benefit students with autism of any age who fit the description above.

TASH Resolution On Augmentative And Alternative Communication Methods And The Right To Communicate - (1992, revised in 2000), The Association for the Severely Handicapped (TASH). This document provides an important and compelling statement regarding the basic need and right to communication for all individuals regardless of severity of disability.

Online Videos

The Language Stealers - This animated video is about communication and Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC). (3 min)

In My Language - This video, by Amanda Baggs (a woman with ASD), explains what communication means to her. (8 min)

Speaking is Not Communication - Autism does not Speak - This video, by a woman with ASD, describes how she's impacted in the area of communication and that having language does not consist solely of being able to speak. (4 min)

Online Training

Autism Internet Modules - Current communication modules of interest include: “Functional Communication Training”, “Speech Generating Devices”, and “Picture Exchange Communication System”. While freely available, viewing the modules requires registration.

Communication in Autism - This is a video of a lecture on communication and autism, by Dr. Rhea Paul professor at Yale University. (1 hr 50 min)

Enhancing Communication using Environmental and Visual Supports and Strategies - This presentation outlines various ways to support communication for individuals with autism using visual supports.

Functional Communication Training - Autism Professional Development Center. This resource provides an overview, evidence-base, steps for implementation, and an implantation checklist.

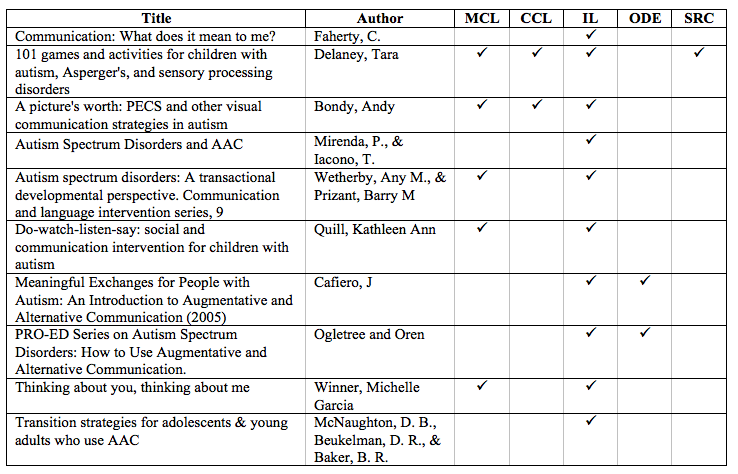

Practical Books and Audiovisuals Available on Loan

Many libraries, including the ones below, have books and audiovisuals on ASD and communication to loan.

Multnomah County Library (MCL)

Reference Line: 503.988.5234

Clackamas County Libraries (CCL)

Library Information Network: 503.723.4888

SRC: Jean Baton Swindells Resource Center for Children and Families

The resources are available to family and caregivers of Oregon and Southwest Washington.

503.215.2429

Below is a list of books and videos on ASD and communication that can be borrowed from the sources indicated. Check with your library for additional titles.

Books

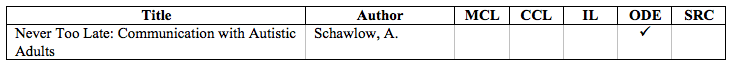

Audio

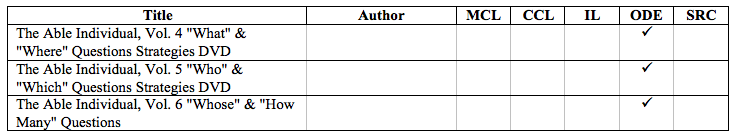

Video

Copyright © 2016 Columbia Regional Program