-

Preparing Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder for Adulthood A Transition Toolkit for Educators

UNIT 3.3: Executive Function and Organization

Key Questions

- What is executive function and organization?

- Why teach executive function skills to youth with ASD?

- What do executive function challenges look like in youth with ASD?

- Can all youth with ASD learn executive function skills?

- When should I start teaching executive function skills?

- How do I determine what executive function skills to teach?

- How should I teach executive function skills?

- How can I learn more about implementing effective strategies?

- Are there any executive function curriculum or lesson plans I can use with youth with ASD?

Appendices

- Appendix 3.3A: Online and Other Resources

- Appendix 3.3B: Checklist for Organization

- Appendix 3.3C: SUpplemental Lesson Plans for Organization

- Appendix 3.3D: Glossary of Terms

by Phyllis Coyne

The information and practical resources in this unit of The Expanded Core Curriculum is designed to help educational staff and other members of the transition team to understand and provide instruction in executive function skills and organization for youth and young adults with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

This is a resource for you and is designed so that you can return to sections of the unit, as you need more information or tools. You do not need to read this unit from beginning to end or in order. Feel free to print this unit for ease of reading or as an accessible reference. Links to questions, appendices and online resources are provided so that you can go directly to what is most relevant to you at the time.

What is executive function and organization?

According to Dawson and Guare (2004), executive function is “a neuropsychological concept referring to the cognitive processes required to plan and direct activities, including task initiation and follow-through, working memory, sustained attention, performance monitoring, inhibition of impulses, and goal-directed persistence”. Executive function abilities and skills are necessary to organize one’s thoughts, tasks, materials and time, to select and achieve goals, and to understand a problem area and come up with feasible solutions. Because these central processes are required to regulate behavior and to give organization and order to actions and behavior, executive function is often referred to as the brain’s CEO or conductor.

Dawson and Guare (2009) have divided executive function skills into the following 11 categories. Each is defined in the glossary in Appendix 3.3D.

- Response inhibition

- Working memory

- Emotional control

- Sustained attention

- Task initiation

- Planning/prioritization

- Organization

- Time management

- Flexibility

- Goal directed persistence

- Metacognition

Organization usually refers to the ability and skills to create and maintain systems to keep track of information or materials (Dawson & Guare, 2009). It is an area of executive function that receives a great deal of attention, because executive functions are most intimately involved in giving organization and order to our actions and behavior.

Why teach executive function skills to youth with ASD?

Executive function is a core cognitive deficit of ASD (Frith, 1989; Hughes et al., 1994; Ozonoff, 1995; & Ozonoff & Griffith, 2000).(Executive function challenges occurs in a large number of clinical disorders, and, therefore, is not specific to ASD.) Problems with attention control and attention shifting, planning and goal setting, flexibility, organization, time management, memory, self-regulation and metacognition have consistently been described as traits of individuals with ASD (Filler & Rosenshein, 2008; Ozonoff, 1998; Ozonoff & Griffith, 2000, Pennington & Ozonoff, 1996).

Performance is affected even when motivation and intellectual abilities are high. Their challenges with executive function stand out particularly in contrast to the many areas in which youth with average or above intellectual abilities have made significant progress.

The manifestation of executive function challenges, like all the underlying characteristics of ASD, is unique to each individual with ASD. However, whether mild, moderate or severe, executive function challenges significantly affect every day functioning at school, work, community and home.

Middle school, high school and the transition to adult life put increasingly complex demands on working memory, planning, organization, and time management. Some of the rising demands on executive function in secondary school include:

- Multiple assignments and teachers

- Frequent schedule changes

- Classes in different parts of large buildings, in different building and/or community sites

- Organizational methods that vary from teacher to teacher

- More long term assignments

- Limited time frame for homework, community activities and home activities

- Segmentation of tasks

- Prioritizing/postponing

- Set long term goals for adult life (postsecondary goals)

Students may be expected to adapt to a number of organizational methods that vary from teacher to teacher at a time when learning and internalizing even one organization system is a challenge. They are often unable to discriminate major tasks from minor details and allocate time accordingly. As a result, many youth with ASD fail to complete tasks on time, are off task and fail to bring home what is needed to complete homework.

Executive function skills are necessary to face a new challenge or resolve to pursue a goal. Youth with ASD are expected to set postsecondary goals that require the use of executive function skills that they may not have learned.

As students approach the transition from school to adult life, the demands on time management, planning, organization, and goal-directed persistence are particularly pronounced. The impact of these challenges can intensify over time, until these youth become overwhelmed. Skill development in executive cannot be left to chance, at a time when youth with ASD need to respond to more complexities in their world.

Instruction in executive function skills and support for missing or weak executive function skills are necessary for success in secondary school and adult life. Youth with ASD typically do not learn executive function skills naturally through observation or self-awareness and, therefore, are unlikely to acquire many critical executive function skills without direct instruction. When executive skills are explicitly taught, youth with ASD become more effective students, as well as acquire a set of skills that contribute to adult success in postsecondary education, employment, independent living and community participation.

What do executive function challenges look like in youth with ASD?

Some challenges in executive function are more common in youth with ASD. However, the specific challenges and degree of challenge will vary with the individual. Below is a partial list of executive function challenges that may be observed in youth with ASD according to Coyne (1996), Dawson and Guare (2009), Filler and Rosenheim (2008), and Ozonoff (1997). It is organized by the 11 executive function skills categories used by Dawson and Guare (2004).

Response Inhibition

- Acts without thinking

- Interrupts others

- Blurts out answers to questions

- Talks too loudly

- Does not understand cause and effect

- Fails to foresee consequences and act accordingly

- Does not walk away from confrontation or provocative behavior by others

- Unable to “read” reactions from others and adjust behavior accordingly

- May pick smaller, immediate reward over larger, delayed reward

Working Memory

- Forgets order of steps

- Loses place in sequence when interrupted

- Loses track of the "why" of a situation

- Fails to keep track of assignments and classroom rules of multiple teachers

- Forgets events or responsibilities that deviate from the norm (e.g., special instructions for field trips, extracurricular activities)

- Forgets multistep directions

- Does not answer questions about familiar material posed in an unfamiliar manner and to generate new ideas

- Does not generalize knowledge or skills to a similar situation

- Has difficulty holding information, (e.g., phone number) and doing action, (e.g., dial number)

Emotional Control

- Overreacts to small problems

- Does not self-regulate behavior

- Becomes easily overwhelmed when things don’t turn out the way the think they should

- Appears overwhelmed by a relatively simple task

- Views a simple problem-solving situation as insurmountable

- Is easily over stimulated and has trouble calming down

- Gets overly upset about “little things”

- Has low tolerance for frustration

- Cannot accept not getting what he wants

Sustained Attention

- Is frequently off task

- Becomes easily distracted

- Has difficulty refocusing or re-engaging with the task or activity

- Has difficulties with concentration

- Does not complete chores or assignments

- Is easily bored

Task Initiation

- Is immobilized or unable to begin a task

- Is slow to initiate tasks, especially less desired tasks

- Has difficulty getting started even with a routine task

- Leaves everything for the last minute

Planning/Prioritization

- Has difficulty with or unusual manner of sequencing

- Has difficulty setting goals

- Has difficulty initiating a plan

- Becomes overwhelmed by a task that should be relatively simple

- Has difficulty prioritizing tasks

- Cannot break down long-term projects

- Does not differentiate between details vs. the “big picture

- Starts project without necessary materials

- May not leave enough time to complete tasks

- Skips steps in multi-step task

- Has difficulty relating story chronologically

- Wastes time doing small project and fails to do big project

- Has difficulty identifying what material to record in note-taking

- May include the wrong amount of detail in written expression (too much detail, too little detail, irrelevant detail)

Organization

- Frequently loses personal belongings, such as keys and personal electronics

- Has a backpack full of crumpled paper and random objects

- Cannot find things in backpack or locker

- Has a messy or disorganized locker, binder and/or work area

- Does not bring home the books, supplies, and worksheets necessary to complete homework

- Wastes time looking for needed items

- Loses or forgets to bring necessary materials to class or home

- Loses or forgets to turn in assignments

- Loses books, papers, notebooks

- Has difficulty organizing thoughts

Time Management

- Does not complete tasks within required timeframe

- Has difficulty with the signals for the passage of time

- May not understand “minute”, “wait”, and “later”

- Over focuses on watches/clocks or schedules

- Asks many repetitive time and schedule questions

- Does not hand in assignments on time

- Misses deadlines at work

- Is late for school, work or other appointments

- Leaves everything for the last minute

- Has difficulty orienting self in time or knowing what is coming next

- Does not understand the passing of time

- Becomes very anxious when waiting

- Lacks sense of urgency related to time

- Keeps putting off homework

- Does not finish homework before bedtime

- Makes poor decisions about priorities when time is limited (e.g., coming home from school to finish project rather than playing with friends)

- Cannot spread out a long-term project over several days

Flexibility

- Resists change of routine

- Upset by changes in plans

- Shuts down or becomes anxious with a change in a normal activity

- Becomes easily overwhelmed when things don’t turn out the way they think they should

- Has difficulty changing from one point of focus to another

- Has only one solution to a problem

- Resists transition to new activities

- Gets stuck on one topic

- Has difficulty adjusting to different teachers, classroom rules, and routines

- Resists following the agenda of others

- Has concrete thought processes

- Has awkward and rigid thought processes

- Has difficulty making transitions

- Has difficulty coping with unforeseen events

Goal-directed persistence

- Does not follow tasks to completion

- Chooses “fun stuff” over homework

- Difficult to prepare for, or to begin, less-desirable work activities

- Does not initiate a plan and monitor performance

- Loses track of the "why" of a situation

- Unwilling to engage in effortful tasks to earn money

- Unwilling to practice without reminders to improve a skill or performance

Metacognition

- Does not self monitor

- Has only one solution to a problem

- Is unaware of impact of behavior on others

- Does not evaluate own performance (e.g., in sports event; school or work performance)

- Has limited self awareness

Can all youth with ASD learn executive function skills?

All youth with ASD need executive function skills and can learn them or learn strategies to compensate for missing ones to varying degrees. However, many people presume that, since executive function is a cognitive process, instruction in executive function skills is only for youth with ASD who have average or above intellectual abilities and believe that those severely impacted by ASD and/or with significant intellectual challenges will not benefit from instruction related to executive function skills.

Youth who are more impacted by ASD may not develop the same number or level of executive function skills as others, nevertheless they can and should develop or learn to compensate for executive function skills. Many types of support strategies have been developed that can help more impacted youth and young adults with ASD to compensate for their lack of or weak executive function skills. For instance, they may compensate for challenges in working memory, organization and time management by learning to follow routines, schedules, work systems and organization systems that others have developed for them. They may learn to maintain their belongings, area and systems following a checklist or routine. They may be taught to self regulate their behavior using pictorial cue cards and/or routines. Although they may not use the thinking skills normally associated with executive function, skills in the use of these visual supports allow them to do the activities that the thinking skills usually enable. Indeed, the value of learning to use supports to compensate for executive function challenges extends to youth and young adults with ASD of all intellectual abilities.

When should I start teaching executive function skills?

Support for executive function challenges and instruction in executive functions skills should start early in a child’s life. In typically developing children, executive function skills begin to develop in early infancy, then progress gradually through the first two decades of life (Dawson and Guare, 2009). Dawson and Guare (2009) have identified the time periods in which 11executive functions skills emerge as follows. (Please note that definitions for these terms can be found in the glossary.)

- Infancy: response inhibition, working memory, and emotional control

- Childhood: flexibility, sustained attention, and task initiation

- Adolescence: planning/prioritization, organization and time management

- Late adolescence to early adulthood: goal-directed persistence and metacognition

Almost all of these executive function skills have emerged by 8th grade. It is more difficult and usually takes longer for children and youth with ASD to learn executive function skills, so it is essential to teach developmentally appropriate executive function skills throughout the school years. Since they are already likely to be behind in skills, the development of executive function skills cannot be left to chance or begun in the final years of school. Without early instruction, the impact of executive function challenges can intensify over time and drastically affect performance at school, work, community and home. Even with instruction, some youth and young adults may not be functioning successfully on their own and will require a plan for how these issues will be addressed in adult life.

How do I determine what executive function skills to teach?

Executive function challenges like all the underlying characteristics of ASD fall along a continuum and differ in each individual with ASD. Therefore, assessment of the pattern of strengths and weaknesses in a youth’s executive function skills is key to establishing goals in necessary executive function skills for youth with ASD. Without an assessment of executive skills, a youth with ASD may be taught unnecessary skills, while critical skills are not developed.

A good assessment of executive function skills collects information from a variety of sources, including:

- Formal assessment

- Behavior checklists and rating scales

- Parent, teacher and student interviews

- Observations at school, work, and in the community

- Review of work and organization system

- Environmental assessment

Formal assessment

There is no single test or even battery of tests that identifies all of the different features of executive function. Educators, psychologists, speech-language pathologists, and others use a variety of tests to identify problems. Some of the more recent tools for assessment of neurological functioning that are used to determine eligibility for learning disability by school psychologists can reveal particularly useful information.

The evaluator must understand that youth with ASD may not perform well on formal, standardized assessments due to their complex challenges. Performance on the test may more accurately reflect how the youth performs in a new situation, with new materials, and/or with a new person than what the test intended to assess. Therefore, caution must be exercised in the use of and interpretation of results from the many commercially available, formal tools that assess components of executive function. The standardized scores from such testing cannot be the only basis to make decisions about a youth’s executive function skills.

Behavior Checklists and rating scales

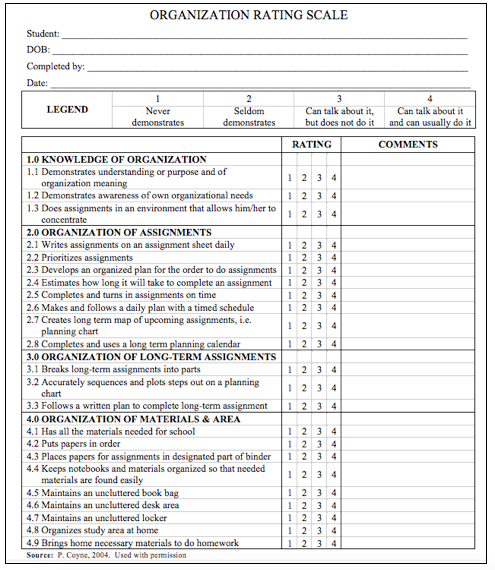

Checklists and rating scales, completed by those who know the youth with ASD well, are an excellent source of information about executive function skills. A number of standardized checklists and rating scales, which include both parent and teacher versions, such as Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Functions (BRIEF), Child Behavior Checklist/Teacher Report Form, and Brown ADD Scales (for adolescents) are commercially available. Links to several free checklists on executive function, such as Executive Skills Questionnaire for Children: Middle School (Grades 6-8) are provided in Appendix 3.3A under Assessment. In addition, Organization Rating Scale is found in Appendix 3.3B.

Parent, teacher and student interviews

When assessing a youth’s executive functioning, information must be gathered from those who know the youth with ASD best, such as parents, teachers and the youth with ASD. According to Dawson and Guare (2004), some key areas of inquiry with teachers and parents are about how well the youth with ASD is able to:

- Work independently,

- Organize and keep track of materials,

- Initiate tasks,

- Plan and execute activities,

- Plan for long-term projects,

- Study for tests,

- Manage negative emotions,

- Manage behavior when stressed,

- Control impulses,

- Follow complex directions,

- Complete and turn in homework, and

- Handle long-term assignments

During the interviews, it is important to identify: 1) specific behaviors that demonstrate strong/weak executive skills, 2) circumstances (people, places, times) under which the problem is most/least likely to occur, 3) previous successful/unsuccessful interventions, and 4) capacity and receptivity of the people and/or environment to change. This will usually require asking follow up questions. If the checklists or rating scales are completed before the interviews, the interviewer should be able to come prepared to ask questions in specific areas of challenge for the youth. (Dawson And Guare, 2009)

When possible, it is valuable to interview the with ASD to learn his perspective on his executive function strengths and challenges, as well as any strategies that he has to compensate for any weaknesses in executive functions. However, youth with ASD typically lack the self-awareness and insight to recognize problems in executive function, or are unable, because of developmental, cognitive, or communication limitations, to articulate the nature of the problems they are experiencing.

Observations at school, work, community, home

Observation provides the opportunity to see executive function skills in the real life daily demands of each environment. When the rating scales and interviews are completed, the evaluator will know the primary concerns and the times or activities in which the behaviors of concern are most likely to be observed. Then decisions about when and where to observe the youth with ASD can be made. The following will help to gather useful and representative information during observations.

- Collect both objective data (e.g., percentage of time on task) as well as a running record of the youth’s or young adult’s behavior throughout the observation.

- Observe the physical environment to determine if there are factors about the space that might be contributing to the problem or could be changed to reduce the problem.

- Watch to see how the youth or young adult is instructed and provided with information.

- Observe on more than one day. Several short observations spread over several days may be more useful than one long observation on a single day.

- Observe in multiple settings. This is particularly important if the youth’s problems relate to poor impulse control or regulation of affect, since these behaviors are likely to be more evident in unstructured situations such as in the hallways, in the cafeteria and at lockers.

- Observe the supports that were effective during the observation, such as checklists, visual schedules, templates, visual examples, written directions, and timers.

- Watch for how the youth or young adult knows:

- What work is to be completed

- Where it is to be completed

- Where to begin and end tasks

- What to do when one is finished

Review of work and organization system

Reviewing samples of work, such as tests, written assignments, assignment sheets, and day planner pages can provide important information on skills such as error monitoring, planning, and organization, which, in turn, may yield ideas for visual supports and other strategies. The review of the youth’s organization system includes looking at his backpack and locker to get a better sense of his ability to organize his belongings and personal space.

Environmental assessment

Another excellent means for gathering useful information is environmental or ecological assessment. This type of assessment examines a variety of factors that may contribute positively or negatively to actions that require executive function skills. Another outcome of environmental assessment can be to identify types of supports that could be provided to help a student perform actions related to executive function. A more complete description of environmental assessment can be found in Unit 3: The Expanded Core Curriculum for Youth with ASD.

Goals

The assessment helps definite the specific behavior(s) related to executive function that need improvement and helps identify annual IEP goals. It is vital to determine what skills the youth will have by the end of high school to reasonably enable him to meet his postsecondary goals. The focus must be beyond what the youth needs now to function; it must address what the youth will need for his desired future work, education and independent living.

Select one executive function skill for initial intervention and identify a specific behavioral goal based on one or two behaviors, which if increased or decreased would lead to better performance for the youth. Identify those skills that are most critical for success over time and focus on those.

How should I teach executive function skills?

Executive function skills and compensatory skills need to be taught explicitly. The strategies used will differ depending on the strengths and challenges of the individual youth with ASD. There are four steps that can help youth with ASD with their executive skills:

- Develop and put support structure in place

- Teach to use supports

- Teach skills to improve executive functioning

- Teach thinking about executive function skills

Each of these approaches is interrelated, although they are described individually.

Support structure

For youth with executive function challenges, the first step is to develop and provide supports that that will reduce the necessity for them to use executive skills to accomplish tasks and reach goals. This step involves developing and presenting visual supports and other supports or modifications to utilize strengths and reduce the impact of the executive function challenges in as unobtrusive and “normalized” manner as possible. It may include: 1) providing visual supports for clear information, expectations and reminders, 2) modifying the environment for clarity and to prevent interfering stimuli, and 3) changing the nature of the tasks to be performed.

As discussed in Unit 2: Supports, visual supports provide key support to youth and young adults with ASD. All visual supports should assist the youth to understand:

- What work is to be done

- Where it is to be done

- How much is to be done

- Where to begin and end tasks

- What is the time factor

- What to do when one is finished

The following are some examples of potential supports:

- Concrete, pictorial or written sequential list of work to be completed

- Concrete, pictorial or written daily or weekly schedule

- Computers or electronic organizers that incorporate calendars

- Templates or jigs of tasks

- Concrete, pictorial or written reminders

- Template/diagram/photo for organization of work area

- Visual reminders of equipment/materials needed in instructional area or in binder

- Case for highlighters, pens, pencils, calculator, ruler, paper clips and scissors

- Color coded binder with to do and done sections

- Time timers & analog clocks for passage of time

- Event based cues for passage of time for more impacted youth with ASD

- Computers or watches with alarms, text messages

- Checklists and "to do" lists, estimating how long tasks will take

- Long assignments broken into chunks and assigned time frames for completion

This toolkit provides links to a number of visual supports for executive function and organization. Organization and Time Management offers suggestions and provides examples of support strategies for organization and time management. Links to other specific examples of visual supports can be found in Appendix 3.3A under Instructional Material and in Unit 2.

It is equally important to modify elements of the environment to meet the youth’s sensory and social needs, which includes consideration of the seating arrangement, the effect of other students in the area and sensory stimulation. This helps set the stage for the youth to learn.

Modifying work with visual structure also helps to reduce the negative effects of executive function challenges. According to Stratton (1996), these modifications may include:

- Giving one problem/question at a time

- Highlighting the relevant information

- Crossing out the problems that do not need to be done

- Drawing boxes where answers should go

- Using alternative ways of responding

Specific examples of these and other visual structure can be found in Adapting Instructional Materials and Strategies.

Involving the youth in planning supports as much as possible, usually results in supports that the youth will be more motivated to use and is the best fit. This is an important part of providing any supports.

The transition team should anticipate that as an individual grows and changes, the structure may be adjusted, but the need for supports seldom goes away. Supports may be necessary throughout the youth’s life in order for him to demonstrate and function at his full potential.

Teach to use supports

Youth with ASD do not necessarily know how to use supports when they are first presented to them. Therefore, they should be explicitly taught how to use them with lots of opportunity to practice until they are able to independently use the support structure. For instance, if a youth is given a pictorial sequential list of work to be completed, he will need to be taught to follow each picture, mark off completed work, and proceed to the next task.

Once the youth with ASD is competent in the use of the supports, the structure is not faded or removed. Instead a system to reinforce and monitor the youth’s continued use of the supports must be implemented.

Some youth will be sensitive to being different. They need to know that it is not a sign of weakness or stupidity to use lists, assignments sheets, or graphic organizers. Everybody needs help with something and uses different things to help them.

Many youth with ASD will always need others to develop and maintain supports for them. They are likely to need accommodations in the workplace, postsecondary education and in community activities. These young people need to learn to ask for the supports that they need while they are in high school, so they are able to request needed accommodations in adulthood.

Teach skills

Youth with ASD will not acquire missing executive function skills just because they have gotten older. To improve executive functioning, they need to be directly taught skills and to be given frequent opportunities to use the skills. The procedure used to teach executive function skills will differ depending on the skill being taught, the context in which it will be used, and the level of the youth with ASD.

Depending on the complexity of the skill being taught and the degree of challenge for the individual, the skills need to be taught very gradually and potentially over a long time until the youth uses the skill independently. For instance, a student may first be provided with a completed assignment sheet with when due, what to do, materials needed, when to do it, and where to turn it in. Then the student may be taught to copy the information from an overhead or from an assignment sheet of proficient student he sits next to at a designated time. The youth may start by writing one assignment, and eventually progress to writing all of his assignments for a day, then every day. Some youth will learn more complicated systems, such as writing an assignment from a teacher’s verbal directions and asking for clarification if he does not have all the information.

Recording assignments is only one skill in being able to do an assignment. Demonstrating this skill does not mean that he knows how to follow his assignment sheet or do the assignment. He may require instruction in skills for completing and turning in the assignment. This may include being taught a specific routine in support of completing assignments and the steps he cannot perform.

Teachers can effectively teach many critical executive skills during group instruction, if they employ universal design principles and support the underlying characteristics of ASD. For instance, to teach generalization, teachers in several classes may take time during class to teach students how to study for tests in the context of real class exams and not simply as a study skills exercise in several classes.

One effective tool for teaching executive function skills is graphic organizers, also known as semantic mapping or thinking maps. Graphic organizers can be used for lower level thinking, such as remembering facts and memorizing test-taking strategies or can be used for higher order thinking to enhance students' thinking, planning, and problem solving. The same graphic organizer can be used for lower or higher level thinking depending on the level of questioning that the teacher attaches to the assignment. MAAPSS: Manual for Adolescents with Asperger's Syndrome Piloting Social Success provides graphic organizers for goals, problems solving, and other areas of executive function. A number of additional links to sites with free graphic organizers is provided in Appendix 3.3A under Instructional Material.

Priming is another effective instructional strategy. Before a situation occurs the youth with ASD reviews and may rehearse what will happen and how he will handle it. Reviewing and rehearsing in advance can be used with any executive function skill challenge, but it is particularly effective for problems with flexibility, emotional control, or response inhibition. More information on priming may be found in the Transitioning Between Activities module of the Autism Internet Modules.

The National Professional Development Center for ASD has determined evidence-based practices for youth with ASD and provides EBP briefs that include step-by-step directions for implementation and checklists. The following evidenced-based practices on their site are particularly effective in instruction of different executive function skills

Regardless of what strategies are used, active involvement of youth with ASD in planning and implementation of strategies is an essential component of the development of executive function skills. In addition, when youth choose strategies, goodness of fit with current skills is more likely, as is the actual use of the strategies.

Instruction in executive function skills may occur in a variety of settings. Middle schools and high schools that employ homeroom or advisor programs, in which teachers interact with students outside of content area classes, can employ a group coaching process during those sessions. The teacher could quickly ask each student to report on what his work plan for the day is or how well he followed the plan from the previous day (Dawson and Guare, 2009). Instruction in executive function skills may also occur during classes, such as study skills, transition skills, career exploration, life skills, and communication/social skills.

Whether instruction is provided 1:1 or in a group, it is necessary to monitor and reinforce use of the targeted executive function skills. Additional ideas and specific examples for teaching executive skills can be found in Appendix 3.3A under Instructional Material.

Teach thinking about executive skills

Just teaching actions related to executive function skills is not enough. Youth with ASD need to develop both a cognitive understanding of executive function skills and develop the ability to think about executive function skills. They need to understand the purpose and meaning of instruction in executive function skills, be aware of their own challenges in executive function, and eventually have their own personal plan for how to both use the skills they have and compensate for weak skills.

The purpose of instruction in executive function skills needs to be explicitly explained in a manner that the youth can understand. It may be as simple as, “Here’s what we’re working on and here’s why.” In addition, the thinking process for various executive function skills needs to be explained. This process includes providing explanations, guidance and questioning at an appropriate level for a student. For instance, a part of teaching about goals is that “goals are something you think about and action plans are a sequence of activities you physically have to do” (Dawson and Guare, 2004). Youth need to know the difference to create and follow through on action plans.

Cognitive Behavioral Therapy is an effective approach for the discussion about the “why” underlying the production of a skill, which is critical for youth with average or above cognitive and language skills. Approaches such as social narratives, Social Thinking, Hidden Curriculum, and The Incredible 5-point scale (look in the module list) are cognitive strategies that have been developed for individuals with ASD.

How can I learn more about implementing effective strategies?

Educators will have to choose between strategies for teaching executive function skills, but may not be aware of how to implement some of the strategies that are most effective. There are some excellent online resources, as well as conferences, to help you learn more about strategies. Some of these are list under Online and Other Training in Appendix 3.3A.

Two online resources are particularly noteworthy. The Evidence-Based Practice Briefs of the National Professional Development Center on ASD provides step-by-step directions for implementation and checklists. The Autism Internet Modules (AIM) provides free training on the following strategies that can be used to teach executive skills:

- Cognitive Scripts

- Rules and Routines

- Self-Management

- Reinforcement

- Structured Teaching

- Structured Work Systems/Organization

- The Incredible 5-Point Scale

- Transitioning Between Activities, including Priming

- Visual Supports

Evaluation

Evaluating the progress of the youth with ASD should be ongoing. Instruction must be revised, as necessary.

Are there any executive function curriculum or lesson plans I can use with youth with ASD?

There are few if any curricula or lesson plans labeled “executive function skills” or “executive function”. However, a variety of curricula at the middle school and high school levels include skill areas such as organization skills, study skills, life skills, goal setting, problem solving, etc. For instance, the National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center provides lesson plans for goal setting and problem solving under life skills instruction. When using curricula and lesson plans that were not specifically designed for those with ASD, remember to apply principles of universal design and additionally support the unique needs of the individual student with ASD.

More and more social skills curricula and lesson plans, particularly those for social understanding or social thinking, for youth with ASD address executive skills. For instance, Social Thinking curricula by Michelle Garcia Winner directly teach many executive function skills.

Links to lesson plans can be found in Appendix 3.3A under Instructional Strategies. Additional lesson plans are provided in Appendix 3.3C: Supplemental Lesson Plans.

The transition to adulthood will doubtlessly have its ups and downs. Youth with ASD will need to learn how to problem solve and cope with discomfort. They will need all the executive function skills and compensatory skills that they can learn.

Appendix 3.3A

Online and Other Resources

- Executive Function

- ASD and Executive Function

- Assessment

- Instructional Material

- Apps for Organization

- Online Videos

- Online Training

- Practical Books and Videos Available on Loan

- Books

- Videos

The resources listed are available at no cost online. While terminology sometimes differs from Website to Website, the basic concepts are the same. Information is designed to either, support youth and young adults with ASD, or can be adapted for the individual need of the student. Some websites are listed in several sections because of their relevance to more than one area.

Executive Function

Executive Dysfunction - Alfredo Ardila. This paper provides a description of executive function and dysfunction.

Executive Function - P. D. Zelazo, AboutKidsHealth. This site offers a six part series about executive function and how it is developed in infancy, childhood, and adolescence; disorders of executive function; and how to foster its development.

Executive Function Dysfunction: The Newest “Learning Disability” - This presentation discusses executive function, physiology, assessment, and strategies.

Executive Functioning: A New Lens through which to View Your Child - K. Stanberry, GreatSchools, Inc. This article describes executive function and how it works or doesn’t work in children with learning or attention problems.

Improving Executive Function Skills—An Innovative Strategy that May Enhance Learning for All Children - Council for Exceptional Children (CEC). This article includes a list of assessments and strategies to strengthen executive function.

Overview of Executive Dysfunction - L. E. Packer, Tourette Syndrome "Plus". This article provides an overview of executive function and executive dysfunction in children and adults.

Understanding the Eight Pillars of Executive Control

What is Executive Function? - The National Center for Learning Disabilities.This fact sheet describes how executive function affects learning, the warning signs of problems with executive function, and strategies to help.

ASD and Executive Function

Executive Functioning - Michaels, ASPEN. This article provides a brief description of the areas affected by executive function and some general teaching tips.

Organization and Time Management - P. Coyne. This chapter from Higher Functioning Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism provides an overview of ASD and the executive skills of organization and time management for higher functioning youth and young adults with ASD. It offers suggestions and provides examples of support strategies for organization and time management.

Organizational Skills and ASD - Emory Autism Center, Emory University School of Medicine. This article advocates the need for instruction in organizational skills.

Transition to Adulthood: Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD) - Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI). These comprehensive guides provide implications of AS for executive function and organization and a corresponding list of strategies and interventions for employment, postsecondary education, and community participation.

Assessment

Abridged Executive Control Skills Checklist - This abridged version of the Executive Control Skills Checklist addresses behaviors in eight executive function skills. Here is the Quick Test .

Executive Function in Children - N. Hogan. This article discusses executive function and the Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function (BRIEF) software.

Executive Skills Questionnaire for Children: Middle School (Grades 6-8) - This assessment is adapted from Smart but Scattered by Dawson and Guare.

Learning Works for Kids - This site offers questionnaires for parents and kids to determine which types of games can best help kids learn.

Transition to Adulthood Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders (ASD): Age-appropriate Transition Assessment - Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI). This guide includes information and strategies on executive function and organization for in the sections on postsecondary education, employment and community participation.

Instructional Material

Adapting Instructional Materials and Strategies - J. Stratton. This chapter from Higher Functioning Adolescents and Young Adults with Autism provides an overview of ASD and executive skills related to academics for higher functioning youth and young adults with ASD. It offers suggestions and provides examples of support and instructional strategies for academics.

Boardmaker Activities – Flexible Thinking - Boardmaker Online. These are free boardmaker activity and picture communication symbol boards for flexible thinking.

Cognitive Behavior Modification - This article provides a description and steps for cognitive behavior modification, an effective strategy to teach executive skills.

Do2Learn Social Skills Toolbox - This site offers downloadable graphic organizers (scroll down menu on left side of page) and strategies for problem solving.

Environmental Cues, Supports, and Strategies - L. E. Packer, Tourette Syndrome "Plus". This article discusses visual cues, cognitive strategies, and other tips for dealing with disorganization or other types of executive dysfunction.

Evidence–based Practice Briefs - National Professional Development Center for ASD. These briefs include step-by-step information on how to implement strategies and checklists for each strategy. Of particular note related for instruction in executive function are: reinforcement, self management, structured work systems and visual supports.

Executive Skills in Children and Adolescents: Assessment and Intervention - Peg Dawson. This presentation includes specific steps for teaching executive skills in a variety of areas.

Five Homework Strategies for Teaching Students with Disabilities - C. Warger, Autism Society of Greater Cleveland (ASGC). This article provides five strategies to help students with disabilities get the most from their homework.

Flexible Thinking vs Rock Thinking - Autism Inspiration. This lesson helps students differentiate between different examples while using the language of "Flexible thinker" and "Rock Thinker."

FreeMind - FreeMind is a free mind-mapping software.

FutureLab - This document provides a free library of printable ready-made interactive thinking guides.

Getting Your Life Organized - This page for individuals with ASD provides tips to organization.

Graphic Organizer Templates - This site offers 40 downloadable templates to use in a word processing program.

Homework and Beyond! - M. G. Winner, Social Thinking. This article discusses teaching organizational skills to individuals with ASD.

How to Study.org - This site provides resource to help high school and college students develop effective study skills/time management skills.

It Was Due When? Time Management Tips - L. E. Packer, Tourette Syndrome "Plus". This page provides tips students can use in estimating how long it will take to do a task.

Jott - This is a tool for students to send themselves reminders, homework assignments, to-do lists, summaries of class instruction ,etc by using a cell phone to send emails or voice messages.

Kidspiration - Inspiration Software, Inc. This page shows examples of use of Kidspiration. Although the examples are not specific to planning, this software can be used to create pictorial graphic organizers to outline steps of tasks. Link to free 30-day trail from this page.

Lesson Plan Library: Student Development - National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC). This site offers 80 lesson plan starters on life skills instruction, of which 22 are related to choice making. The topics related to choice making include, decision making, goal setting, problem solving, self-awareness, and self-advocacy skills. (Scroll down the page to number 19 - 40)

Linking Assessment to Intervention - Peg Dawson and Richard Guare

MAAPSS: Manual for Adolescents with Asperger’s Syndrome Piloting Social Success T. Hass, Columbia Regional Program. This manual provides goals and exercises for executive function and organization. Organization IEP Goals start on page 79 and Organizational Visual Exercises start on page 85.

Mind Tools - This site offers some free articles about time management, problem solving, decision making, and more. There are interactive quizzes to assess abilities in a given area. This site is for a general audience and is selling a service.

Online Stopwatch - Online countdown timers.

Pocket Mod - This site provides a free, recyclable personal organizer and study guide, which can be used in a variety of ways.

Problem Solving Overview: Questions to Ask Yourself - Asperger’s Association of New England. This document offers sample questions for educators working with individuals with ASD.

Putting Feet on My Dreams, A. Fullerton - Unit 3 of this self-determination curriculum provides lesson plans for executive function areas of organization, goal setting, self awareness, etc.

RecallPlus - This free mindmapping tool can be used to organize notes, create flashcards, make use of 3D tools and more.

Self-Management - S. M. Edelson, Autism Research Institute. This article describes how to teach self-management.

Teaching organizational skills - D. Adreon, & H. Willis, Autism Support Network. This article provides an example of how parents and teacher can teach organizational skills.

Thinking and Planning Gallery - Inspiration Software, Inc.. This page shows examples of graphic organizers for students to plan their work, resulting in better-organized portfolios, research projects and other projects. Link to free 30-day trial from this page.

Time Management - This page provides a few tips on time management.

Time Management: Learning to Use a Day Planner (WWK11) - National Resource Center on ADHD. This article discusses the selection and use of a day planner.

Time Management Tips - L. E. Packer, Tourette Syndrome "Plus". This article offers some ideas for improving time management or time awareness.

Apps for Organization

Apps Designed with Transition in Mind - This chart provides a variety of free and low cost apps for iPhone, IPod Touch and IPad with a section on organization.

My Homework - Rodrigo Neri. This is a free application for Mac or iPhone. The application keeps track of homework, classes, projects and tests.

Picture Planner - Cognitopia Software. This is an application of Windows, Mac, iPad, and iPhone/Touch. The application is an icon-based personal planner, which helps people with cognitive disabilities live more independently. The desktop software (on Windows or Mac) can be used to sync with the free iPad, and iPhone/Touch application. (Cost: Free 30-day trial for Windows and Mac. Free for iPad, and iPhone/Touch)

Picture Scheduler - P. Jankuj & T. Van Laarhoven. This is an application for the iPhone. The application allows you to attach a picture/auditory task lists or video-based instructional materials. It also allows you to set alerts to remind you of the task. A tutorial is available in the “Contact & Support” section of the website. (Cost: $2.99)

A Spectrum of Apps for Students on the Autism Spectrum - This chart provides a variety of free and low cost apps for iPhone, IPod Touch and IPad with sections on organization and study skills.

Time Timer - This site offers timers, watches, and software products that show the passage of time.

Online Videos

Asperger's Syndrome - Executive Dysfunction - A.J. Mahari. This video shows a woman, diagnosed with Asperger's Syndrome in adulthood, talking about her experience of what is defined as "Executive Dysfunction" as being her aspie way of functioning.

Executive Functioning: Definition and Strategies for Success - This video presentation defines executive functioning, explains how this difficulty impacts learning and then offers strategies for success. (9 min)

Executive Function Skills Part 1 - M.I.N.D. Institute Lecture Series on Neurodevelopmental Disorders. This video provides an overview of executive function deficits, and a variety of strategies and techniques that can be used in school. (1 hr. 16 min)

Online Training

Autism Internet Modules (AIM) - This site offers a number of free training modules on strategies that can be used to teach executive skills, such as Cognitive Scripts, Rules and Routines, Self-Management, Reinforcement, Response Interruption/Redirection, Structured Teaching, Structured Work Systems and Activity Organization, The Incredible 5-Point Scale, Transitioning Between Activities, and Visual Supports.

Supporting Successful Completion of Homework, - This module discusses challenges that individuals with ASD face with regard to homework. It provides some strategies and tools to address unique challenges with organization, sensory needs, and academic differences. (A free registration and login are required)

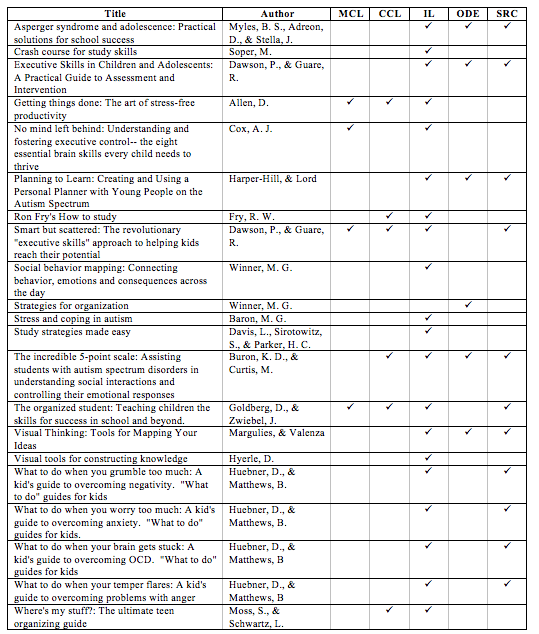

Practical Books and Videos Available on Loan

Many libraries, including the ones below, have books and videos on executive function for youth with ASD to loan.

Multnomah County Library (MCL)

Reference Line: 503.988.5234

Clackamas County Libraries (CCL)

Library Information Network: 503.723.4888

SRC: Jean Baton Swindells Resource Center for Children and Families

The resources are available to family and caregivers of Oregon and Southwest Washington.

503.215.2429

Below is a list of books and videos on executive function for youth with ASD that can be borrowed from the sources indicated. Check with your library for additional titles.

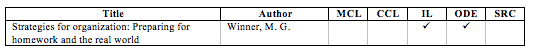

Books

Videos

Appendix 3.3B

Checklist for Organization

Appendix 3.3C

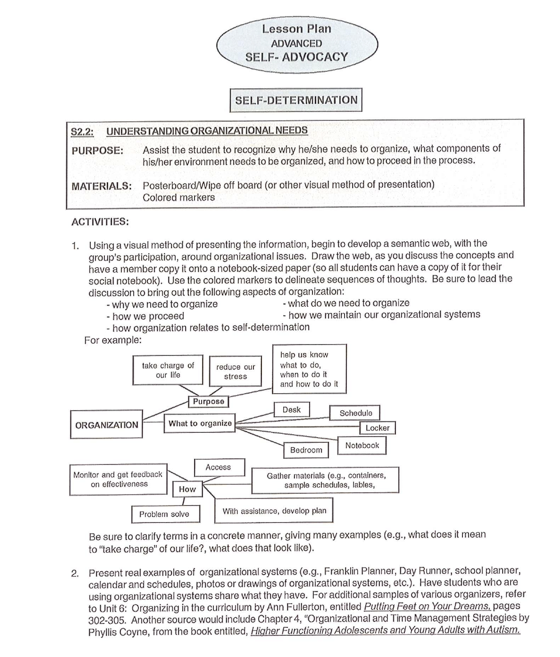

Supplemental Lesson Plans for Organization

Source: Coyne, P. (1996) Organization and Time Management Strategies. Used with permission.

Appendix 3.3D

Glossary of Terms

Abstract reasoning deficit. Difficulty with the ability to analyze, organize, and synthesize information—including making inferences

Complete. Reaching the self-set or other-set goal

Emotional Control. The ability to manage emotions in order to achieve goals, complete tasks, or control and direct behavior

Executive functions. The ability to plan, execute and thoughtfully monitor behavior toward a specific goal

Flexibility. The ability to revise plans in the face of obstacles, setbacks, new information or mistakes. It relates to an adaptability to changing conditions.

Goal. Setting a goal

Goal-directed persistence. The capacity to have a goal, follow through to the completion of the goal, and not be put off by or distracted by competing interests

Graphic organizer. An instructional tool used to illustrate content information. Examples of graphic organizers include: outlines, timelines, tables, charts, webs, lists, pictorial representations, etc.

Higher Cognitive Functions. Tasks that require complex problem-solving skills outside the social domain

Initiate. Begin or start task

Memory deficits. Difficulty using recently stored information to facilitate learning

Metacognition. The ability to stand back and take a birds-eye view of oneself in a situation, such as how one problem solves. It also includes self-monitoring and self-evaluative skills (e.g., asking, “How am I doing? or How did I do?”).

Mini-Schedule. Involves the presentation of a task list that communicates a series of activities or steps required to complete a specific activity. Mini-schedules can take several forms including written words, pictures or photographs, or workstations.

Organization. The ability to create and maintain systems to keep track of information or materials. Organization requires an understanding of what needs to be done and a plan for implementation.

Organize. Obtain and maintain necessary materials and aids to completing sequence and achieving goal

Pace. Establish and adjust work or production rate so that goal is met by specified completion time or date

Personal Digital Assistant (PDA). PDA is a small computer that incorporates a calendar, task list, and date book. These visual devices can help depict daily schedules and tasks and remind the user of important events through the use of audible and visual alarms.

Plan. Develop steps towards goal, identify materials needed, set completion date

Planning/Prioritization. The ability to create a roadmap to reach a goal or to complete a task. It also involves being able to make decisions about what’s important to focus on and what’s not important.

Prioritize. Establish ranking of needs or tasks.

Response Inhibition. The capacity to think before you act – this ability to resist the urge to say or do something allows us the time to evaluate a situation and how our behavior might impact it.

Scaffolding. Providing explanations, guidance and questioning at an appropriate level for a student

Self-awareness. Self-knowledge and an understanding of how one is seen by others.

Self-monitor. To keep track of, or obtain an intermittent awareness of, how one is doing relative to one's purpose.

Self-regulation. To strategically modulate one’s emotional reactions or states in order to cope or engage with the environment more effectively

Sequence. Arrange (and enact) steps in proper order spatially or temporally

Shift. Move from one task to another smoothly and quickly. Respond to feedback by adjusting plan or steps.

Sustained Attention. The capacity to maintain attention to a situation or task in spite of distractibility, fatigue, or boredom

Task Initiation. The ability to begin projects without undue procrastination, in an efficient or timely fashion

Time Management. The capacity to estimate how much time one has, how to allocate it, and how to stay within time limits and deadlines. It also involves a sense that time is important.

Working Memory. The ability to hold information in memory while performing complex tasks. It incorporates the ability to draw on past learning or experience to apply to the situation at hand or to project into the future.

Next: Unit 3.4 Sensory Self-Regulation

Copyright © 2016 Columbia Regional Program