-

Preparing Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder for Adulthood A Transition Toolkit for Educators

UNIT 3.2: Social Skills

Key Questions

- What are social skills for youth with ASD?

- Why is social skill instruction critical for youth with ASD?

- How do I identify and prioritize social skills to teach?

- Can I use the same social skills instruction for all my students with ASD?

- What do I do if my student with ASD does not want instruction in social skills?

- What are the elements of effective social skills instruction for youth with ASD?

- Are social skills groups the only way to deliver social skills instruction?

- What are the essential ingredients to setting up and running social skills groups for youth with ASD?

- How often should social skills intervention or groups be offered, and how long should sessions be?

- Where does peer training fit into social skills instruction?

- Which social skill interventions for youth with ASD are supported by research?

Appendices

by Brad Hendershott

Social Skills for Youth with ASD

The information and practical resources in this unit are designed to help educational staff and members of the transition team to increase the social competency, social participation, social acceptance, and independent functioning of youth and young adults with ASD.

Please be aware that there is no agreed upon dividing line between social skills and communication. Therefore, this subject area of the expanded core curriculum for youth and young adults with ASD is not mutually exclusive from Unit 3.1: Communication.

This is a resource for you and is designed so that you can return to sections of the unit, as you need more information or tools. You do not need to read this unit from beginning to end or in order. Feel free to print this unit for ease of reading or as an accessible reference. Links to questions, appendices and online resources are provided so that you can go directly to what is most relevant to you at the time.

What are social skills for youth with ASD?

As a group, there is remarkable diversity among individuals with ASD. Yet they all share difficulties with social communication. These difficulties vary widely depending upon severity. The DSM-V diagnostic criteria for ASD effectively captures the range of social communication difficulties observed among individuals with ASD, each of whom exhibit:

- Deficits in social-emotional reciprocity, ranging, for example, from abnormal social approach and failure of normal back-and-forth conversation; to reduced sharing of interests, emotions, or affect; to failure to initiate or respond to social interactions.

- Deficits in nonverbal communicative behaviors used for social interaction, ranging, for example, from poorly integrated verbal and nonverbal communication; to abnormalities in eye contact and body language or deficits in understanding and use of gestures; to a total lack of facial expressions and nonverbal communication.

- Deficits in developing, maintaining, and understand relationships, ranging, for example, from difficulties adjusting behavior to suit various social contexts; to difficulties in sharing imaginative play or in making friends; to absence of interest in peers.

Defining Social Skills

Spence (1980) described social skills as “appropriate social behavior within a particular social situation.” Indeed, social competence is largely determined by the degree to which an individual remains within the boundaries of behaviors and responses that others deem appropriate. Demonstrating social competence is remarkably complex, drawing upon a broad array of inter-related skills including language comprehension, spoken language, paralinguistics (e.g., facial expression, gesture, tone of voice), memory, cognition (e.g., perspective-taking), and executive skills (Rowe et al., 2014).

In Rubrics for Transition for Students on the Autism Spectrum, Wessels (2004) provides a useful framework by identifying key social skill priorities that our students will need to function successfully in adult life:

- Taking the Perspective of Others

- Being in Control of Emotions

- Showing Respect for Self and Others

- Accepting Responsibility for Actions

- Interacting Well in a Group Setting

- Disagreeing Appropriately

- Being Willing to "Give and Take"

- Handling Teasing and Bullying

- Working Towards Group Goals

- Working Well with Co-Workers

- Working Well with Limited Supervision

- Making an Appropriate Impression

- Having Two-Way Conversations

- Getting People's Attention Appropriately

- Practicing Personal Grooming and Hygiene

- Participating in Leisure Activities

- Developing and Maintaining Friendships

- Maintaining Positive Relationships

- Dating Successfully

- Making Healthy Sexual Choices

- Avoiding Substance Abuse

For individuals at earlier developmental levels with more substantial needs, Wessels identifies a pared down, more concrete set of social skill priorities:

- Interacting Well in a Group Settings

- Making an Appropriate Impression

- Listening

- Working Well with Co-Workers

- Promoting Own Ideas effectively

- Considering the Ideas of Others

- Being Willing to ‘Give and Take’

- Using Manners Appropriate to Workplace

- Being Customer Friendly

- Answering the Telephone

- Making Effective Phone Calls

Many of these skill areas require proficiency with a subset of skills. Within Rubrics for Transition, each skill has been task analyzed (i.e. broken down into discrete, teachable sub-skills). For example, ‘Makes an Appropriate Impression’ includes: "dresses appropriately for situations", "is well groomed – hair clean and combed", "deodorant applied", "teeth brushed", "shaved", "maintains acceptable distance", and so forth.

Social skills extend well beyond basic interaction skills such as the use of polite forms (e.g., please, thank you) and conversational turn taking. Hans Asperser wrote, “The teacher who does not understand that it is necessary to teach autistic children seemingly obvious things will feel impatient and irritated.” (Aspy and Grossman, 2007). It is the myriad of ‘seemingly obvious’ behaviors with which students with ASD need specific, explicit instruction. For example, youth and young adults with ASD benefit from being taught to understand and navigate different kinds of relationships, including romantic or sexual attachments. A youth with ASD attracted to a woman may demonstrate his interest by following her around and going to her house, even after she has directly or indirectly indicated she was not interested in a relationship. The youth may not have an adequate understanding of her perspective, and his attempts to see and speak with her may be viewed as threatening or dangerous. In response to these specific concerns Buron (2007) authored a guide for youth and young adults titled A 5 is Against the Law: Straight Up Social Boundaries.

In the workplace select social skills may be of particular importance, such as how to respond to others based upon their role (e.g. supervisor vs. co-worker), or the use of appropriate language and humor for the workplace (e.g. avoiding profanity, racial or sexually charged comments). Employers consistently place social skills and the ability to get along with others at the top of desired employee characteristics, above other important competencies such as the ability to complete job tasks or knowledge of work-related subjects. An employer may reason, “I can train an employee on how to complete tasks; I can’t teach them how to be socially appropriate”. Social skills are of utmost importance for gaining and maintaining employment, and typically there will be specific social skill expectations tied to individual workplaces, which transition programs should assess.

In the community, expected social behaviors are linked to specific contexts. For example, it is important to offer your seat on a bus to an elderly or disabled when all or most seats are taken, or not to strike up a conversation with a stranger using a public restroom. It is important to know how to ‘code switch’, adjusting our language and style of communication based on the role of that person.

For students with ASD who have more limited cognitive and/or language abilities, a skill-based approach is often used to teach specific social behaviors without extensive explanation to teach why the behavior is important and how it impacts the thoughts and responsive behavior of others. In contrast, students with average to above average cognitive and language skills may be taught various pro-social behaviors along with an underlying understanding of ‘why’ the behavior is important; how the behavior impacts the thoughts, feelings, and responses of others. This secondary layer of instruction, which teaches an understanding of why a behavior is important, is a significant feature which distinguishes social thinking from social skills instruction; the former requires sophisticated language skills along with the ability to self-reflect and think meta-cognitively. Michelle Winner, who is credited with coining the terms social thinking, provides a more through explanation of the topic at Social Thinking.

Why is social skills instruction critical for youth with ASD?

The lack of social competence often has a devastating impact on an individual’s life, undercutting relationships and social participation, interfering with employment, and impeding integration into the community. The National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC) found that students with disabilities who transition from high school with higher levels of social skills are more likely to be employed, participate in post-secondary education, and experience independent living than those with lower levels of social skills (Benz, Yovanoff, & Doren, 1997; Halpern, Yovanoff, Doren, & Benz, 1995; Roessler, Brolin, & Johnson, 1990). An employment skills survey conducted by Victoria University of Wellington (2006) listed “Strong Interpersonal Skills” as the top sought after attribute by employers. Wessells (2004) stated, "The goal of special education is to produce adults who are as productive and independent as possible." Therefore, social skills instruction is critically important in maximizing the likelyhood that our students with ASD will live independent, productive, and fulfilling adult lives.

Watson stated that “Successful Transition programming requires a change in mindset on the part of special educators. They must give up the academic model of service and think in terms of real life expectations” (Wessells, 2004, p. viii). Youth with ASD require direct, explicit instruction to acquire targeted social skills identified through assessment. While many social skills can be initially acquired in small group or one-on-one teaching, it is critical that we take that next step and help our students with ASD learn how to perform or carry over newly acquired skills to various "real world" situations, contexts, and people. In other words, new skills can be established in a decontextualized situation. But we can't stop there; we need to to provide opportunities to practice in natural contexts with stand-by support that is gradually faded thus fostering independence.

For youth and young adults with ASD, social skills encompass an adherence to countless unwritten rules of social behavior, such as maintaining appropriate personal space during conversation, knowing which topics are appropriate based on who you are with, and disagreeing with someone without insulting them. Social expectations range from the concrete (using a quiet voice in the library) to the subtle and complex (knowing how to filter what you say based on who you are talking to and the situation). People with ASD exhibit varying degrees of impairment in the underlying social thinking that people use to regulate their social behavior. Those most impacted by ASD may appear ‘mind blind’, lacking any awareness of the thoughts and perspectives of others. In contrast, those with ASD who appear "high functioning" typically do have an awareness of the thoughts and emotions of others, yet their perspective taking skills are limited or lack sophistication in comparison their neurotypical peers. These limitations with social thinking result in difficulties navigating the social world; connecting and "getting along" with others, establishing and maintaining relationships, and so forth. Fortunately, research tells us that we can teach our students with ASD how to take perspective, to think about what others are thinking, to read emotions - and then how to use this knowledge to become more socially competent.

Most neurotypical individuals naturally develop an intuitive awareness of the perception and perspectives of other people. In the presence of others, we instantaneously and effortlessly form a mental model of how our own behavior is likely to be perceived. We initiate some behaviors, and inhibit others, in an ongoing and almost automatic effort to influence how we are perceived. Consider the incalculable choices made each day, which are influenced by our awareness of the perceptions of others, from the words we choose to the clothes we wear. Consider how differently people would behave without the constant influence of an awareness which tells us how our behaviors are likely to be perceived, and without a mental model which projects how others are likely to treat us in response. This leads to a central point often made in presentations made to educators on autism; the unusual, difficult, or challenging behavior exhibited by many people with autism is not due to a willful desire to disrupt, annoy, insult, or manipulate. Rather, behaviors result from skill deficits and limitations in social thinking, which are at the core of the disability.

Without a natural and intuitive awareness of the thoughts and perspectives of others, people with ASD may exhibit a wide range of behaviors which may be perceived as rude, thoughtless, odd, strange, and perhaps even threatening or dangerous. Problems of perception are exacerbated by the fact that the person with ASD may have no physical indicators of an underlying disability. Those with high functioning autism, or Asperger Syndrome, are often quite intelligent and verbal, especially around areas of intense interest. When the person with ASD makes a social error, others may be harsh in their judgment because the person with ASD may have a typical appearance, or may be well spoken on a preferred topic and therefore, some reason, the person with ASD must ‘know better’. It would be as if when looking at a person in a wheelchair we thought, “They can climb those stairs. They’re choosing not to”. The neurologically based impairment in social thinking and social skills is as real as an orthopedic impairment, even if it is less physically obvious. In work, community, or residential settings, some people may not ‘see the autism’, failing to understand that the person with autism thinks, processes, and experiences the world in a fundamentally different manner from neurotypical individuals.

How do I identify and prioritize social skills to teach?

Before beginning social skills intervention with a student on the autism spectrum, it is essential to assess current competencies and strengths, along with areas of need. Initial and ongoing assessment may include checklists, rating tools, and standardized measures.

Use of Checklists and Rating Tools

A number of tools exist to help identify skills to work on, such as Scott Bellini’s Autism Social Skills Profile (ASSP). Checklists are ideally completed by one or more informants who have observed the youth or young adult with ASD over a significant period of time (e.g. three months or longer), and can report on functioning in a variety of contexts and situations. It is important that the checklists include items, which reflect functional, real world expectations.

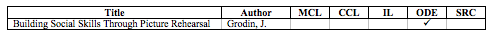

In How to Find Work That Works for People with Asperger Syndrome, Hawkins (2004) provides a social skill checklist to be completed by a rater who is advised to take the perspective of a supervisor when completing the form, and carefully observe the individual with ASD in the work setting. Then the observer rates social skills in ten key areas. The checklist is reprinted below, with permission:Use of Standardized Measures

In addition to non-standardized tools, there are variety of standardized instruments to help assess social skills and relationship development. The Texas Statewide Leadership for Autism Training provides a comprehensive list of Social and Relationship Evaluation tools.

Assessing the specific demands of the environment

Sometimes referred to as an ‘ecological inventory’, an assessment of the environment to determine which social skills are needed for specific settings is very useful in identifying practical, real-world targets for instruction. For example, if a student is or will be working at the high school snack cart, then an observation along with interviews of those operating in the environment may be conducted to determine the social demands of that context.

Social programs delivered in isolation from real-world contexts, without ‘taking the pulse’ of real-world social expectations and demands may be of little or no benefit in terms of preparing the student for adult life. This fact underscores the importance of assessment to ensure teaching of social competencies, which lead to increased acceptance, integration, and independent functioning where it counts most, beyond the classroom.

Involvement of the student with ASD in determining social skill priorities

It is important to determine what the youth or young adult with ASD values, enjoys, and views as important and meaningful in their life. When possible, engage the student in discussions of future goals and aspirations. For example, this Dream Sheet may be completed.

A self-assessment of social skills may be conducted through by a written inventory or checklist of social skills. Attempt to determine if there are social skills, which the individual with ASD would like to improve, so that they can have a voice in choosing what to work on. The connection can be made between the skills being targeted within the social program and identified personal goals and aspirations.

Consideration of social validity

In selecting and prioritizing social skill goals, it is important to consider what other people in the student’s life view as top priorities. Parents, siblings, friends, teachers, roommates, supervisors, and co-workers can provide extremely useful information, and will often report on social errors or behaviors serve as the greatest barriers to social acceptance and integration in real world settings. Also, when others value the skills being targeted in the social program, they may be more likely to assist with generalization by offering support, encouragement, and reinforcement resulting in better outcomes for the student with autism.

Can I use the same social skills instruction for all my students with ASD?

While there are excellent social skills and social thinking curricula available, most educators find that there is no ‘cookbook’ or single curriculum which can be followed in a linear manner with either individuals or groups. Those experienced in supporting students with ASD draw from a variety of resources, along with generating ideas or building upon and modifying others, to match interventions to the skill being targeted. Not only does each student with ASD function at different levels, but also each youth has their own temperament and unique profile of skill deficits and relative strengths. Quality social skills instruction is highly individualized and based upon thoughtful assessment conducted prior to beginning instruction. Some make the mistake of skipping assessment and going straight into intervention, taking a approach which reasons ‘people with ASD have social impairments, so we will work on social skills’. Generic skills are then targeted, such as having a conversation, turn taking, etc. However, this approach may not to lead to intervention which matches individual students’ skill deficits, and fails to teach essential skills needed to function in the real world.

Time must be taken to get to know the student, to learn about the environments he or she currently or will be functioning in, and to learn about the people in that student’s life. Assessment will identify skill deficits specific to individual students. For example, one student may aggressively correct and talk over others, saying things, which appear rude or tactless with little or no understanding of how his behavior is being perceived by others. Assessment of a second student uncovers a different set of challenges. Another student with ASD may be overly passive and socially naive, seemingly unable to initiate interactions or respond to open-ended questions with anything more than a word or two. Accordingly, instruction will need to be individualized to meet the unique needs of each of these students. The first student may need instruction on how to state opinions and disagree respectfully with an understanding of the thinking and responses of others based on his behavior. The other student may need practice to initiate interactions and comment on topics being discussed by the group. The first student with ASD may not need or want visual support to help understand the concepts, possessing language processing skills which allow a primarily verbally mediated approach. The second student may become easily overwhelmed with verbal information and benefit greatly from the visuals to concretize abstract concepts.

What do I do if my student with ASD does not want instruction in social skills?

Invariably, some youth and young adults with ASD will resist social skills instruction. It is important to acknowledge how fragile and emotionally vulnerable many students with ASD are. Secondary affective disorders may develop and co-occur with the ASD. For example, the development of impairing levels of anxiety is as high as 84% for youth and young adults with ASD (White et al., 2009). Some high functioning students may have developed extreme defensiveness around the topic of ASD or disability and react badly to disability-related language. A student may be agitated when asked to participate in activities to increase social skills and social understanding. These students may not yet be available for or open to direct teaching of pro-social skills. Consider the following ideas:

- Develop a relationship by exploring areas of interest and strengths. You will need the relationship first.

- Be authentic, and avoid communicating in a manner, which the student views as patronizing.

- Listen to concerns and acknowledge feelings, without judgment or contradiction.

- Avoid arguments and power struggles.

- Provide opportunities for choice and control.

- Consider an alternative role. Rather than being the “student getting help” the individual with ASD may be more responsive in an assistant role, helping to plan or run an activity. Build upon student strengths and capacities.

- Don’t forget reinforcement. Even high functioning students may respond to something as simple as earning a candy bar for participating in-group and adhering to expected group rules.

- Integrate area of intense or deep interest.

- Group students carefully, and if a combination isn’t working, change it. Some students are simply not ‘group ready’ and need to be worked with individually.

- Think ‘outside the box’. If pullout sessions in the speech office have gone poorly, consider working with the student in different environments. The student may view the pullout space itself, and traveling to is, as stigmatizing. Listen to their concerns regarding peer perception, and be willing to negotiate options, which allow you to deliver support while respecting individual dignity and desire for privacy.

- Reframe the experience by calling it something different. For example, rather than coming to group to work on ‘social skills’, redefine the experience by establishing a ‘Horticulture Club’, with plant-related activities providing the context within which to work on various social skills.

- Monitor for mental health or behavioral conditions outside of your scope of practice. In rare cases, individuals may present with an identified or unidentified psychiatric condition such as schizoid personality disorder or borderline personality disorder co-occurring with the ASD. Seek an outside referral and/or additional specialized support from a professional familiar with these conditions.

What are the elements of effective social skills instruction for youth with ASD?

The Council for Exceptional Children (CEC) Division on Career Development and Transition (DCDT) published a "fast facts" document on social skills instruction and transition-aged individiauls with disabilities. The authors dentified the following as essential characteristics of social skills programs:

- Integrate social skills instruction across the curriculum (e.g., general education and community).

- Use a direct instruction curriculum to teach communication, interpersonal, conversational, negotiation, conflict, and group skills in context.

- Provide opportunities for students to practice communication, interpersonal, conversational, negotiation, conflict, and group skills in context.

- Assist students to use problem-solving skills when difficult interpersonal situations arise in context.

- Provide parent and school staff information and training in supporting age-appropriate social skill development for their child, taking into consideration the family’s cultural standards.

- Use augmentative communication (AC) and assistive technology (AT) devices to encourage communication for students who use AC/AT.

- Use ecological assessments to identify the social skills students will be expected to perform in each context.

- Provide opportunities for students to practice social skills that foster authentic social interactions that foster development of friendships.

- Teach students to self-evaluate their use of social skills in appropriate contexts.

- Teach students social expectations for various environments (e.g., church, school, work, recreation).

Social skills research specific to ASD provides additional guidance on which approaches and elements may be employed to produce better outcomes for students. A meta-analysis conducted by Bellini, Benner, & Hopf (2007) of fifty-five studies examining school-based social skills interventions for students with ASD yielded three key findings

Finding #1: Effective social skill instruction should occur more frequently than is typically the case, with school personnel looking for opportunities to teach social skills as frequently as possible throughout the day.

Rather than viewing social skills as another subject to be taught, like math or history, at a certain time with a specific teacher, it should be viewed as something taught throughout the day, in multiple settings, by all the adults participating in the student’s educational/transition program. To be successful, this requires a shift in mindset, with communication and coordination of social skill goals, teaching techniques, key vocabulary, and reinforcement. A dramatic increase in minutes of service on the Individual Education Plan is not what is being suggested. Significant increases in the ‘dosage’ of social skills instruction can be achieved when a team is aware of, and pursuing social skill instructional goals throughout the day, embedded in daily activities and routines.

Finding #2: Social skills instruction is best implemented in multiple, naturalistic settings to ensure maintenance and generalization.

Bellini found that a major weakness of many social skills interventions is a failure to produce adequate maintenance and generalization effects due in part to training which, according to Gresham at al. (2001), takes place in “contrived, restricted, and decontextualized” (p. 340) settings such as resource rooms and pullout settings. Those delivering social skills instruction must avoid a ‘treat and hope’ approach; to deliver instruction and hope that there is a positive impact in the ‘real world’. Educators may work to ensure that instruction yields meaningful outcomes by first assessing the demands of the natural setting (i.e. ecological inventory); then teach and support practice of those skills which will be important in work, community, and other authentic settings. If skills have been identified which will be important in a vocational setting such as a coffee shop (e.g. greeting customers, taking orders, asking for clarification), it follows that the acquisition and performance of these skills will be most effectively taught in an actual, or closely simulated, coffee shop.

The Distributive Education Clubs of America (DECA) has developed tools for setting up School-Based Enterprises to prepare students for the transition from to school to work or college. These enterprises may be modified so that youth and young adults with ASD can learn a variety of social skills in the meaningful context of setting up and operating a business (e.g. a school store). For example, a Florida high school set up a school-based enterprise; a coffee cart run by students with ASD who prepare, market, and sell coffee for teachers, staff, and students. More information and a free comprehensive guide to beginning an enterprise can be found on the DECA website.

Pullout sessions, which are valuable in providing structured opportunities to provide direct teaching, must be accompanied by opportunities to perform/practice targeted skills in naturalistic settings, with stand-by coaching, feedback, and reinforcement. For example, a social skills group which has been learning how to start and maintain a conversations in pull out sessions should lead to later sessions which occur in more naturalistic settings such as in a hallway, or at a restaurant, where those conversational skills may be practiced with stand-by coaching and feedback being systematically faded. If a group has been working on following ‘unwritten rules’ in places like the library, then follow up with a trip to the library to practice using those pro-social skills where they are actually needed.

Finding #3: Social skill interventions should match the skill deficit, rather than making the student ‘fit’ into the desired strategy.

It is important to have a specific and clear idea of what the student needs to work on, and then select your intervention or strategy based on the type of skill deficit exhibited. For example, if a student with ASD is getting too close to others when speaking with them and touching other inappropriately, then the social skills intervention should involve teaching an understanding of ‘rules’ governing personal space, levels of intimacy, and so forth. Many programs and authors have developed tools and lesson plans to assist in teaching these concepts. Now, for the student who is having personal space and touching issues, a general social skills program to teach conversation, cooperation, and friendship skills will not be well matched to the students’ specific skill deficits.

Additionally, instruction should be developmentally and age appropriate and well matched based upon the student’s cognitive and language abilities. A student more impacted by ASD will quickly become overwhelmed and lost in a social thinking lesson, which relies heavily on verbal explanations and reference to abstract concepts such as the thoughts and perspectives of others. A higher functioning student may grow impatient, bored, and even angry about instruction, which focuses on basic skills and does not appear to acknowledge their intellect.

Social Validity

Social validity refers to the extent to which others in the student’s life (e.g. teachers, parents, friends) view social skills objectives and interventions as important and acceptable. Educators should strive to ensure that their social skills instruction has social validity. This is important because as Bellini (2007) states, ‘If the intervention lacks social validity, consumers are less likely to exert the effort necessary to implement the intervention…’ It is desirable for parents, teachers, and others to view the goals and interventions as socially valid because they are then much more likely to support the student in multiple environments across the day in achieving those social goals. This is achieved by bringing parents, teachers, and others into the conversation at the very beginning and finding out what is important to them. Ongoing conversation and collaboration is encouraged by sharing what students are working on, key concepts and vocabulary covered, and by giving parents and others specific recommendation on how they can support carryover of pro-social concepts and behaviors.

One way Michele Winner helps ensure social validity, along with promoting maintenance and generalization, at her San Jose Center for Social Thinking, is by using the last 15 minutes of every one-hour session to share lesson goals, key vocabulary, and tips with parents and caregivers. Winner developed a companion resource for those implementing social thinking instruction with higher functioning students titled, “Implementing Social Thinking Vocabulary and Concepts into our Home and School Day”.

Are social skills groups the only way to deliver social skills instruction?

Once those planning and delivering instruction have a clear idea of what each student specifically needs to work on, educators should draw on a rich variety of methods to ensure acquisition and performance of given skills or competencies. It is important to know exactly what is to be taught and then draw on whatever methods will help the student make meaningful progress. This is important to mention because in some cases, educators may settle upon a particular method or service delivery model (e.g. pull out social skills group) that may not match what will work for a particular student in helping them develop the social competence needed to succeed in the "real world". The highest quality social skills interventions tend to draw upon a variety of methods (Provencal, 2003) and service delivery models depending upon the goals being targeted. A sampling of common methods for teaching social skills are listed below:

- Direct Instruction provides explicit, concrete explanations of specific social skills, such as all the behaviors required to be a part of a group, or interpret the expressions and body postures of others.

- Modeling (including video modeling) provides live or video models of specific behaviors or skills for individuals with autism to view, such as modeling how to greet others by name, give a compliment, or react appropriately to a problem/frustration.

- Role-Playing provides opportunities to practice specific behaviors and behavior sequences, such as initiating an interaction with a peer. Students may benefit from scripts, which provide specific language and structure the sequence; scripts are then faded.

- Self-monitoring directs a student to pay attention and track performance on a specific behavior, such as paying attention to the ‘group topic’ (versus a preservative or intense are of personal interest). Reinforcement is typically provided for both self-monitoring and skill use.

- Incidental Teaching is used to teach social skills in the settings in which they are needed. The person providing the intervention takes advantage of naturally occurring situations to teach, prompt, and reinforce targeted pro-social behaviors, such as asking for assistance when needed or keeping the body turned toward communication partners. (As applied to social skills training, some may also be describe this as ‘Social Coaching’)

- Cognitive-Behavioral Intervention (CBI) is often used with higher functioning students to address emotional-self management, by teaching the student how to recognize their own physiological and emotional states, leading into learning techniques become better regulated (i.e. relaxed), along with person problem-solving strategies. This approach requires language and cognitive skills to self-reflect and think meta-cognitively.

- Structured activities and games provide a structured context to learn about and practice targeted pro-social skills, such as cooperating, sharing materials, giving and receiving compliments, and so forth.

- Social Stories™ provide individuals with ASD the information they need to understand specific social situations and perspectives of others. Stories Stories share information and explain events and explanations. They are often written in first person, but with older students are often in third person. Stories are individualized based on the person with autism’s level of functioning.

- Perspective-Taking or Teaching Theory of Mind is another teaching technique geared towards higher functioning students, and emphasizes the importance of teaching students with autism how to think about what other people think and feel, along with how others are likely to behave in response to our own behavior.

- Peer Mediated interventions utilize specific protocols to train peers on how to monitor for and/or prompt and reinforce individuals a variety of pro-social communication skills produced by the person with autism. Peer mediated approaches also are employed to enhance social integration and social participation among individuals with ASD.

The National Professional Development Center (NPDC) on ASDs provides implementation steps, research basis, and so forth. Similarly, Autism Internet Modules (AIM) from the Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence Disabilities (OCALI) provides instructional modules for some of the strategies listed below.

What are the essential ingredients to setting up and running social skills groups for youth with ASD?

TABLE: Essential Ingredients to Enhance Social Skills Groups (adapted from Krasny, Provencal, & Ozonoff, 2003)

A wide variety of semantic maps and visuals designed to assist in teaching adolescents with high functioning autism various social skills and social thinking concepts may be viewed at MAAPSS.

How often should social skills intervention or groups be offered, and how long should sessions be?

The literature does not yet provide a clear answer to this question, in part because research has not yet identified how treatment intensity and/or duration impacts efficacy. On average, social skill groups tend to meet weekly for 60 or 90 minute sessions for a minimum of 12 weeks (Reichow & Volkmer, 2010). However, this does not account for other activities outside of the formal sessions, which may teach or reinforce social skills learning, such as individual problem-solving and social coaching by teachers, speech-language pathologists, and parents, etc. In regard to school-aged individuals with ASD, Bellini (2007) stated, ‘school personnel should look for opportunities to teach and reinforce social skills as frequently as possible throughout the school day.’

Bellini is making a critical point: social skill outcomes will be much stronger if everyone supporting the youth with ASD is aware of the learning goals and assists with instruction whenever opportunities arise throughout each day! Consider a high school student with ASD who is learning how to time their initiations and avoid interupting or "talking over" other people (a priority skill identified via assessment). For a higher functioning youth, we would also want to provide instruction regarding the the negative or positive thoughts and responses of other people associated with well-timed initiations versus interuptions. If the SLP works on these skills twice a week during 45 minute sessions, goal attainment may be slow and/or have poor carry-over. Learning and generalization is going to be vastly enhanced if the other adults (teachers, parents) that interact with the student know what the social skills goals are and how prompt and reinforce the student. We must work to ensure social skills instruction is being infused throughout the day, providing exponentially greater opportunities to learn.

Gresham, Sugai & Horner (2001) recommended that social skill interventions should be offered with greater frequency and intensity than is common practice. They found that 30 hours of instruction spread over 10 to 12 weeks was insufficient. This equates to 2.5 to 3 hours per week of social skills intervention, an amount in excess of what appears on many Individual Education Plan’s (IEP) for students with ASD. While more frequent, more intense social skills interventions appear called for, we must acknowledge resources and educators who are spread increasingly thin and who perhaps are struggling to meet even bare minimum levels of service. These circumstances call for setting up structures, which make the best possible use of the resources available. For example, even though a social skills group can only meet once per week, mechanisms can and should be implemented to involve others (parents, teachers, peers) in supporting social skill development throughout the day. That way, social skills intervention is not something, which only occurs as a specific day and time, with a certain individual. Instead, social skills intervention is anchored by weekly sessions, and enhanced dramatically by others who support and reinforce targeted skills across settings, situations, and people.

In addition, educators should think flexibly about service delivery. A pullout group has its strengths, but is only one way to teach social skills. A person with ASD may need support with an individual issue or problem, which requires 1:1 help via cartooning, a Social Story™, or other approach. They may need help getting ready for a specific event or situation, such as an interview or a social gathering. Social skill intervention may take the form of a phone call to explain the student and her disability to a supervisor, along with sharing specific support strategies. There are two main points here. The first is to think beyond minutes on an IEP and that social skills is only something taught when a student is pulled out to work with an educator. The second is to think about the whole person and ‘take the pulse’ of their daily experiences in the social world; what they encounter, who they interact with, and any particular challenges which arise (or are likely to arise). We may then use that information to drive intervention efforts to build social competency, which truly make a difference where it counts: in the real world.

Where does peer training fit into social skills instruction?

Peer mediated strategies focus on training peers how to facilitate positive interactions with students with ASD. Programs such as Circle of Friends were developed to train non-disabled peers and others around the student with ASD to promote peer understanding and friendship development. While most of the research has followed younger students with ASD, peer mediated strategies and peer training should not be neglected in social skills programming for youth with ASD.

Effective social skills intervention should be thought of as two-pronged. While it is important to work on targeted social skills for youth with ASD, it is equally important to look at ways the environment can be reasonably adjusted to meet the youth with ASD halfway by:

- Helping those who interact with the person with ASD in vocational, residential, or community settings understand the disability and appropriate support strategies. A young adult with ASD who is starting a new job experience in an electronics repair shop, time spent to brief supervisors and co-workers on strengths, unique challenges, and useful strategies can make the difference between keeping or losing the job. The time spent on communicating with people in this work setting is as important as any time spent working directly with the student improving social skills.

- Establishing a peer network or mentor by recruiting and training neurotypical peers. Choi (2007) wrote, “Peer members are recruited voluntarily on the basis on having known each other in a mainstreamed class, having common interests and hobbies in sports and music, or sharing an on-campus job. It seems to be effective for individuals with autism to establish and maintain on-going and age-appropriate interactions promoting friendship by positive social environment in natural social contexts” (p. 96).

Research investigating peer mediated approaches found only positive effects are observed only when peers receive specific training in how to involve and support individuals with autism in social interactions. In other words, simply placing an individual with autism in a setting with non-disabled peers has little or no effect on improving social competence, acceptance, and integration.

Peer training and disability awareness along with environmental modifications are important because, according to Reichow and Volkmar (2010), “total amelioration of social skills deficits do not occur, and social difficulties remain even in individuals with good treatment.” (In other words, an impairment-based approach which focuses only on change within the individual with ASD is unlikely to produce sought after levels of social integration, ongoing employment, and independence.

Facilitating Activity Based Groups

Activity or recreation-based based groups that integrate a shared interest among the participants (e.g. video games, anime, geology, etc.) are a very good way to set the stage for social interaction among individuals with ASD. That way, the focus may be on the area of deep interest and enthusiasm, rather than the social interaction itself relieving a great deal of pressure on the person with ASD. With a focus on the activity or area of interest, the ‘stage is set’ for social interaction and the potential for friendship, while relieving stress and pressure which a person with ASD might otherwise feel in a ‘friendship’ or social group where the interaction was the primary focus. Participants with ASD are able to draw upon their knowledge of their interest area to anchor conversation, without the pressure of talking about topics, which they know or care little about. As with all ASD interventions, it is useful to integrate special interests, and thereby embed reinforcement, to increase motivation and attention.

Activity-based groups, in many cases, will require some sort of structure and planning provided by the interventions to ensure success. The time that a teacher spends setting up an activity-based group, or helping connect a student with ASD with others, who share his passion, is a powerful and legitimate way to deliver service. It is important to avoid viewing social skills intervention as only something that happens when an interventionist sits down with one or more students with autism to teach something.

Creating opportunities for social participation

Those assisting with transition efforts may create and schedule opportunities for social participation, such as having dinner with a friend or going out to a movie. Many youth and young adults with ASD may need support to identify, plan, and participate in experiences, which people engage in to foster social closeness and connection. Ideally, social programming will not just focus upon change within the youth with ASD. It will also include peer training, supported participation in community activities, emotional support, and friendship development.

Which social skill interventions for youth with ASD are supported by research?

As yet, there is no perfectly clear path for educators to follow in delivering social skills interventions, particularly for older students. There are comparatively very few studies examining social skills interventions for youth and young adults with ASD. In a recent literature review of social skills interventions for individuals with ASD, Reichow and Volkmar (2010) found only three studies published since 2001 which met their minimum inclusion criteria based on methodological rigor and peer-reviewed status. More studies with adolescents and adults with autism are clearly in need.

Acknowledging the paucity of research on social skills interventions, which include youth and adult participants, we turn to social skills research, which includes participants with ASD across age ranges and levels of functioning, with particular interest in outcomes for school-aged and older individuals. The majority of ASD-specific social skills studies examine interventions for preschool children. Three recently published papers, two meta-analyses and one best evidence synthesis, reviewed the research on social skills interventions for individuals with ASD to determine which methods are most effective.

Bellini’s 2007 paper concluded that “results of this meta-analysis suggest that school-based social skills interventions are minimally effective for children with ASD.” and ‘the low treatment effects observed in the present study are consistent with the results of previous social skills intervention meta-analyses (p. 159). In spite of this discouraging assessment, Bellini described three important implications for practice resulting from his analysis of the most successful social skills interventions (see the answer to question 6., “What are the elements of effective social skills instruction for youth and young adults with ASD?”)

Wang and Spillane’s 2009 analysis of 36 studies concludes the following regarding specific social skills interventions:

- Video Modeling (VM) emerged as the strongest social skills intervention and ‘was shown to meet the criteria as an evidence-based practice, as well as being highly effective’. According to the authors’ system ranking effectiveness, VM fell within the ‘moderately effective’ category.

- Peer Mediated strategies fell within the ‘mildly effective range’, with mixed outcomes overall in improving social skills in students with ASD.

- Social Stories met the criteria for being evidence-based, but did not rank above the ‘mildly effective’ range.

- Cognitive Behavioral Intervention (CBI) research has produced highly promising results, but there were too few studies available to rank effectiveness.

Reichow and Volkmar (2010) concluded, “social skills groups and video modeling have accumulated the evidence necessary for the classification of established EBP and promising EBP, respectively” (p. 149). They concluded the following regarding other social skills interventions:

- Applied Behavior Analysis (ABA): “…there is much support for the use of interventions based on ABA, and the use of these techniques should be continued” (p. 159). Examples of social skills taught via ABA in some of the studies included responding to social questions and engagement in conversational exchanges.

- Naturalistic: “While there is enough evidence supporting naturalistic techniques for young children with autism, evidence for older individuals is insufficient” (p. 159)

- Parent Training: Evidence supports recommendation for in increasing social skills with younger students, but inadequate evidence supporting use with older students due to lack of research.

- Peer Training: Training nondisabled peers to support social skills interventions “has much support and should be considered a recommended practice for all individuals with autism” (p. 160).

- Social Skills Groups: Findings tentatively support use of social skills groups to increase skills among medium to high functioning individuals with autism. Authors caution that some studies did not show strong effects, and they reinforce prior concerns that social skills groups may not produce skills, which are maintained and/or generalized. Examples of skills targeted by social skills group research: activity-based problem solving, interaction, sharing, collaboration, pro-social commenting.

- Visual: Includes Social Stories and activity schedules. “Studies using visual supports has positive findings, suggesting they can be an effective method for enhancing social understanding and structuring social interactions” (p. 161).

- Video Modeling: Consistent with other recent research findings, video modeling is “an effective intervention for teaching social skills to individuals with autism” (p. 161).

National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders

The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders (NPDCASD) identified the following as evidence-based practices (EBP) for developing social skills among individuals with ASD from ages 15 to 22:

- Antecendent-Based Intervention: Arrangement of events preceding an interfering behavior to prevent or reduce occurrence

- Modeling: Demonstration of a desired behavior that results in skill acquisition through learner imitation

- Peer-Mediated Instrution and Intervention: Parent delivered intervention learned through a structured parent training program

- Reinforcement: A response occurring after a behavior resulting in an increased likelihood of future reoccurrence of the behavior

- Scripting: A verbal or written model of a skill or situation that is practiced before use in context

- Social Skills Training: Direct instruction on social skills with rehearsal and feedback to increase positive peer interaction.

- Technology Aided Instruction (e.g., computer, iPad, smartphone): Intervention using technology as a critical feature

- Video Modeling: A video recording of a targeted skill that is viewed to assist in learning

- Visual Supports: Visual display that supports independent skill use.

National Autism Center

Also recently published was the 2009 landmark National Standards Report from the National Autism Center (NAC) (updated in 2015), which represents an exhaustive review of the literature on ASD interventions and then ranks instructional methods and programs into the categories of Established, Emerging, and Unestablished. While we will not attempt to summarize the NAC’s findings here, it is important to note that there is valuable information for educators delivering social skills instruction to youth and young adults with autism. For example, the report describes the research-based efficacy of specific instructional methods such as incorporating student interests and obsessions as motivators to complete tasks, or priming students for instruction by reviewing information and materials prior to their use. The primary report and educator supplement are both freely available at the NAC website.

Manualized Programs

With regard to social skills program with a pre-determined scope and sequence of skills and lesson plans, the Program for the Education and Enrichment of Relational Skills (PEERS®) was developed by Laugenson at UCLA and has demonstrated promise in the research. Originially designed for pre-school students, PEERS now has programs designed specifically for adolescents and for young adults. A particularly robust aspect of PEERS as used in clinical settings is the parent training component. That is, parents of students in the PEERS program participated in concurrent sessions to learn what skills were being targeted with their child, and how to support skill development at home and in the community. As stated above, stronger social skills learning outcomes can be anticipated with parents and other others are recruited to learn about the goals as well as methods to promote attainment of targeted goals.

Caution is indicated with regard to the use of any manualized social skills programs due to the need to assess and individualize instruction based upon the unique instructional needs of each student. There is no "one size fits all" or "cookbook" approach to teaching social skills for youth and young adults with ASD. However, skilled practitioners are often able to address common areas of need during social skills groups while individualizing instruction to meet the unique needs of each participant.

Appendix 3.2A

Online and Other Resources

The resources listed are available at no cost online. While terminology sometimes differs from Website to Website, the basic concepts are the same. All supports are designed to either, support youth and young adults with ASD, or can be adapted for the individual need of the student. Some websites are listed in several sections because of their relevance to more than one area.

Social Skills Instruction and Lesson Planning

Autism4Teachers - This autism support website that provides excellent examples and resources for visual supports, social skills among many other topic areas. Although most of the materials are geared to younger children, the ideas can be modified for use with adolescents. A social skills section includes social stories, social curriculum and additional resources.

Autism Social Skills Profile (ASSP) - This assessment tool was developed by Scott Bellini to aid with targeting top priority social skills. The ASSP2 is now available in draft form.

Distributive Education Clubs of America (DECA) - This resource provides guidance for educators interested in setting up enterprises as a context for learning essential skills for college and the workplace.

Dream Sheet- Student Form. A self-assessment tool to assist with post high school goal planning.

Evidence-Based Practice: Social Skills Groups - (2014) National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders. This guide discusses the setting up and running of social skills groups, includes tools to assist with implementation, data collection, etc.

Jill Kuzma’s Social Thinking Weblog - J. Kuzma. This blog includes teaching ideas for social perspective taking skills, emotion awareness and management, conversation skills, interpretation and use of non-verbal communication, and to develop friendship and interaction skills. Freely downloadable visuals are also available.

Making (and Keeping) Friends: A Model for Social Skills Instruction - S. Bellini. This very practical article describes a variety of established methods for delivering social skills instruction.

Moving Toward Functional Social Competence - This resource provides a scope and sequence of social skills, with associated checklists for planning instruction and tracking progress.

Social Skills Lesson Plans for Middle School - Contra Costa County Office of Education. While not specifically designed for students with disabilities, this resource offers lesson plans for explicitly teaching a variety of expected social behaviors such as how to accept criticism or maintaining friendships. Most, if not all, of the lesson would require some modification to meet the unique learning needs of individuals with ASD.

Social Thinking Center - Michelle Winner’s website offers case examples on her blog, links to samples from her books, and information on upcoming trainings.

Texas Autism Resource Guide for Effective Teaching – Social and Relationship Assessment - An overview of standardized instruments to assess social functioning, including a table describing each tool.

Social Skills Strategies

Behavior Stories from the Watson Institute - With some stories written specifically for adolescents, this site offers stories addressing topics including friendship development, personal space, and cooperation. Stories may be downloaded and customized.

Comic Strip Conversations – Podcast - Engaging interview with an SLP experienced in implementing comic strip conversations and social stories.

Do 2 Learn - The website includes a ‘Social Skills Toolbox’ with lessons and visuals to support teaching of skills including “Starting a Conversation’, ‘Volume Control’, ‘Appropriate Topics for Conversation’ among many others.

Multimedia Instruction of Social Skills from the Center for Implementing Technology in Education (CITEd) - This article reviews ways in which technology can be utilized to deliver effective social skills programming to individuals with ASD.

Overview of Social Narratives - From the National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders, this online AFIRM Module provides background and specific steps for implanting social narratives.

ReadWriteThink - This is a free tool for making comic strips to illustrate various social situations.

Social Narrative Bank - A free site which offers social narratives developed by educators throughout Kansas. Look for the link ‘social narratives’ at the top left.

Video Futures Project at the University of Alaska Anchorage - Information available on video self-modeling as a positive behavior support for transitions, job interviews, speech intelligibility, reducing anxiety, activities of daily living such as mobility and dressing, anger management, and dating behavior. The what, when, why and types of video self-modeling are well described.

Visual Supports and Tools

Apps Designed with Transition in Mind - This chart describes a variety of free and low cost apps for iPhone, iPod touch and iPad with a section on Social Skills.

Boardmaker Share - This vast database of freely downloadable visuals expands daily and includes tools to assist in social skills programming including social stories™, semantic maps, vocabulary boards, etc. (Boardmaker or Boardmaker Player required to view/print these resources.)

Comic Life - Comic Life offers a very powerful tool for integrating your own photos and illustrations to build social stories. The tool is available for a free 30-day trial.

Comic Strip Creator - A free web-based tool for developing comic strips to visually illustrate social skills concepts, behaviors, thoughts, responses, etc.

Digistories - A variety of examples of how digital stories may be developed using a wide variety of free applications.

Geneva Center for Autism E-Learning Visuals - This site offers a variety of printable visual supports, including a volume meter, relaxation visuals, schedules, and choice board. Some visuals are accompanied by a tip-sheet, which describes how to use the visual.

GoAnimate - This site allows creation of comics and animations to illustrate social skill concepts.

Imagine Symbols - Imagine Symbols offers 4000 free realistic symbols are available for download for non-commercial use. Import these into your clip art folder for easy access.

Inspiration and Kidspiration - This software allows for quick and easy production of graphic organizers and diagrams to illustrate social skills concepts. Inspiration offers a free 30-day trial download.

Photo Story 3 - This free download (PC only) allows users to assemble digital photos depicting social skills concepts, sequences, etc.

Pics4Learning - Pics4Learning is a copyright-friendly image library of thousands of photographs for teachers and students.

PictureSET, Special Education Technology (SET), British Columbia - Picture SET is a collection of downloadable visual supports that can be used by students. This searchable database provides a wide range of useful visual supports for different curriculum areas, activities, and events. Files may be opened and printed in either Boardmaker or Adobe/PDF format.

ToonDoo - This site allows the creation of cartoon strips with talking and thinking bubbles, which is valuable for educators who want to visually illustrate social situation to teach expected steps, problem-solving, perspectives of others, etc.

Webspiration - This site can be used for developing and sharing graphic organizers to illustrate social skill concepts.

Yodios - This site allows you add audio to any photo using your cell phone, and share the pictures with audio over the web. Creation of web-based picture plus audio sequences may be useful in work and community settings due to ability to access creations from any computer with Internet access.

Peer Mediated Strategies and Disability Awareness

Growing Up Together: Teens with Autism - Sexuality and Relationships

Sexuality Education and Students with ASD

A TEACCH Report on Sexuality and Autism - This documents describes how to match sex education programming to the level of functioning of the individual with ASD.

Organizations with Resources

National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders - The National Professional Development Center on Autism Spectrum Disorders is a multi-university center to promote the use of evidence-based practice for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Evidence-based practice (EBP) briefs have been developed for all 24 identified evidence-based practices. Most of these evidence-based practices are effective with youth and young adults with ASD. Many practices are effective for social skills instruction, such as social narratives, social skills groups and video modeling. Step-by-step directions for implementation are included.

Online Videos

Adult Life Skills Program (ALSP) for People with Autism - (2005) This video illustrates a model which uses ‘life coaches’ to teach youth and adults with autism to teach a variety of critical behaviors, including social communication skills. (5 min)

Autism Center Helps Adult Social Skills - (2009) WBAL 11 - Baltimore, Hearst Television Inc. The is a news video about Towson University giving some students a chance to get an unexpected education in the field of autism. The new Autism Center on campus uses student mentors to help develop the social, language and motor skills of young autistic adults. (2 min)Cell Phones Improve Social Skills for Teens with Autism - (2009) P. Gerhardt. This video is a presentation with some inserted video segments on the use of blue tooth technology use in training in the community. (5 min)

Manners for the Real World: Basic Social Skills - This is a preview of DVD demonstrating how to act in common social situations. The target audience is for ages upper elementary school through adult. Program uses humor to engage audiences. The complete DVD can be purchased at http://www.coultervideo.com

Social Response Pyramid™ Taking Care of Library Books - (2009) L. Falvo. This video demonstrates the use of Laurel Falvo’s educational tool, "The Social Response Pyramid™." She guides her son through a discussion examining why he should only have one library book at a time, and helping him develop strategies for caring for library books without incurring fines.

Social Skills Training in Adolescence - (2010) M. Soloman, UC Davis M.I.N.D. Institute Lecture Series on Neurodevelopmental Disorders. This lecture, given by Marjorie Soloman, explores models for social skills training with focus on issues encountered when working with adolescents and implications for future research. (59 min)

Socialthinking's Channel - (2009) M. G. Winner, Social Thinking. The Socialthinking’s Channel has four introductory presentations on Social Thinking. The full video training sessions, of 1.5 to 3 hours each, are available for purchase at www.socialthinking.com. The titles are:

- Part 1 - Introducing a Social Thinking Vocabulary in Schools and Homes (10 min),

- Part 1 - Talking with Students and Parents about Social Thinking (5 min),

- Part 1 - Executive Functioning and Organizing for Homework: Strategies to Facilitate Learning (7 min), and

- Part 1 - Social Thinking in the Classroom and Across the Day: ILAUGH Model of Social Thinking (8 min).

Commercially Available Videos

Coulter Video - Autism & Asperger Syndrome Videos, Coulter Video

Today’s Man - (2006) Lizzie Gottlieb, Orchard Pictures. ‘Filmmaker Lizzie Gottlieb's brother, Nicky, demonstrated extraordinary mathematical skills as a child, but had difficulty communicating and socializing. Her documentary follows Nicky from age 21, when he is diagnosed with Asperger's syndrome. Facing a world with few avenues of support for adults with Asperger's, Nicky attempts to move out of his parents' house, find a job, make friends and carve out a life of his own.’ – via Netflix.com. ‘The director of the film follows her brother who has Asperger’s Syndrome for six years after he turns 21 as he leaves the safety or his family's home to go out into a world that he is not fully prepared for and that may not be fully prepared for him.’ – (62 min)

Online Audio: Interviews and Presentations

Program 19 – Stephen Shore - Polly Tommey Presents: Autism One Radio Shows. Program 19 is an interview with Stephen Shore, a professor with ASD. Stephen discusses his experience on the spectrum, including social relationships. (30 min)

Teaching Kids with Autism The Art of Conversation - (2009) J. Hamilton, National Public Broadcasting (NPR), Morning Edition. A report on a research project on a social skills intervention – with an emphasis on coaching and practice, not just explanation. (6 min)

Online and Other Training

Autism Internet Modules (AIM) - This site, developed by OCALI, is available through a free subscription. It includes short sections on various supports and strategies and downloadable materials.

Columbia Regional Program - Columbia Regional Program’s Autism Services assists school districts with a focus on staff training and technical assistance. Serving Multnomah, Clackamas, Wasco and Hood River counties in Oregon.

Get the Job: Keep It with Social Skills - M. Rosenshein. This presentation provides information on effective social skills instruction with many examples of social and visual supports for youth and young adults with ASD.

Mind Institute at the UC Davis Distinguished Lecturer Series - The MIND Institute offers free webinars of past lectures. Of particular interest are the ones by Uta Frith on Autism and the Brain's Theory of Mind; two lectures on mirror neurons by Marco Iacoboni on 10/10/2007 and two by Temple Grandin on 2/14/2007, one on Exploring the Mind of the Visual Thinker.

Webinar: ‘Discovering the Power of Video for Teaching Social Skill Success - Teaching Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders & Related Learning Needs’ - L. Hodgdon. In this webinar, current research is highlighted which demonstrates the power of using video as a teaching tool for individuals with autism. Paid membership required to access this resource.

Practical Books and Audio Available on Loan

Many libraries, including the ones below, have books and videos on social skills for youth with ASD to loan.

Multnomah County Library (MCL) - Reference Line: 503.988.5234

Clackamas County Libraries (CCL) - Library Information Network: 503.723.4888

SRC: Jean Baton Swindells Resource Center for Children and Families

The resources are available to family and caregivers of Oregon and Southwest Washington.

503.215.2429

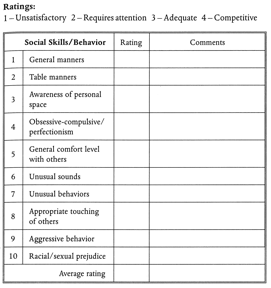

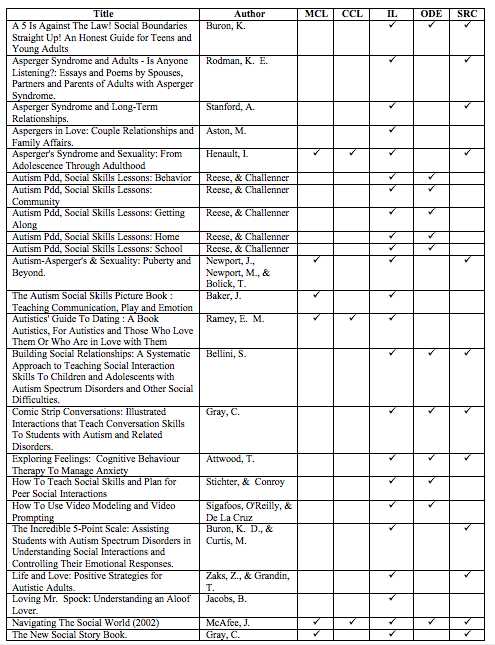

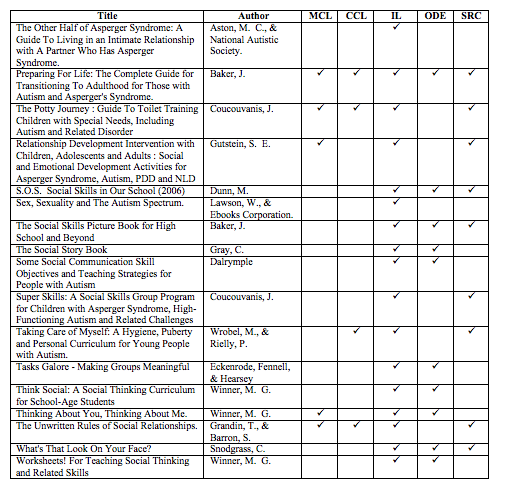

Below is a list of books and videos on social skills for youth with ASD that can be borrowed from the sources indicated. Check with your library for additional titles.

Books

Audio

Appendix 3.2B

Glossary of Terms

5-Point Scale. The Incredible 5-Point Scale, created by Kari Dunn Buron and Mitzi Curtis (2003), provides a visual representation of social behaviors, emotions, and abstract ideas on a scale that breaks social and emotional concepts into 5 parts. Autism Internet Modules (see 5-Point Scale module) (see An Educator’s Guide to Asperger Syndrome, Appendix D, p. 59)

Cartooning. Cartooning promotes social understanding by using simple figures and other symbols, such as conversation and thought bubbles, in a comic strip-like format that is drawn to explain a social situation. An educator can draw a social situation to facilitate understanding or a student, assisted by an adult, can create his or her own illustrations of a social experience.

Comic Strip Conversation™. A form of cartooning developed by Carol Gray, in which missed social information is provided through concrete visual representation of thought between a student and an adult helper.

Computer-aided instruction (CAI). Computer assisted instruction includes the use of computers to teach academic skills and to promote communication and language development and skills. It includes computer modeling and computer tutors.

Evidence-based practices. Evidence-based practices are those supported through research in peer-reviewed journals. There is presently limited agreement on the type and number of research articles needed to become an evidenced practice.

The Power Card Strategy. The Power Card Strategy is a visual aid that uses a student’s special interest to help that individual understand social situations, routines, the meaning of language, and the hidden curriculum in social interactions. This intervention contains two components: a script and the Power Card. (see An Educator’s Guide to Asperger Syndrome, Appendix D, p. 58)

Scripts. Scripts are written sentences or paragraphs or videotaped scenarios that individuals with ASD can memorize and use in real-life social situations. Scripts are used for youth and young adults with ASD who have difficulty generating novel language, particularly when under stressed, but have excellent rote memories. Age-appropriate slang and jargon appropriate to a situation should be included in scripts.

Social Communication Intervention. These psychosocial interventions involve targeting some combination of social communication impairments such as pragmatic communication skills, and the inability to successfully read social situations. These treatments may also be referred to as social pragmatic interventions.

Social narratives. Social narratives are interventions that describe social situations in some detail by highlighting relevant cues and offering examples of appropriate responding. They are aimed at helping learners adjust to changes in routine and adapt their behaviors based on the social and physical cues of a situation, or to teach specific social skills or behaviors. Social narratives are individualized according to learner needs and typically are quite short, perhaps including pictures or other visual aides.

Social Skills Training. Social skills training is used to teach individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) ways to appropriately interact with typically developing peers. Social skills training typically involve small groups of two to eight individuals with disabilities and a teacher or adult facilitator. Most social skill group meetings include instruction, role-playing or practice, and feedback to help learners with ASD acquire and practice skills to promote positive social interactions with peers.

Social Skills Package. These interventions seek to build social interaction skills in children with ASD by targeting basic responses (e.g., eye contact, name response) to complex social skills (e.g., how to initiate or maintain a conversation).

Social skills. Social skills are an array of interpersonal behaviors such as greeting others, commenting/acting on others’ requests or remarks, initiating an exchange, asking others to respond to or engage in an activity, entering into an ongoing social dyad or group, taking turns, taking actions intended to maintain an exchange or social activity, and terminating an interaction (Janney & Snell, 2000)

Social Stories™. A Social Story™ is a story written to describe a situation, skill, or concept. Designed to provide relevant social cues, perspectives and common responses. It is written in a specifically designed format and style (Gray, 1994). The description may include where and why the situation occurs, how others feel or react, or what prompts their feelings and reactions. Within this framework, Social Stories™ are individualized to specific situations, and to individuals of varying abilities and lifestyles. Social Stories™ may exclusively be written documents, or they may be paired with pictures, audiotapes, or videotapes.

Social Understanding. This is the ability for the individual to read social cues and the context and behave accordingly.

Technology-based Treatment. These interventions require the presentation of instructional materials using the medium of computers or related technologies. Examples include but are not restricted to Alpha Program, Delta Messages, the Emotion Trainer Computer Program, pager, robot, or a PDA (Personal Digital Assistant). The theories behind Technology-based Treatments may vary but they are unique in their use of technology.

Theory of Mind Training. These interventions are designed to teach individuals with ASD to recognize and identify mental states (i.e., a person’s thoughts, beliefs, intentions, desires and emotions) in oneself or in others and to be able to take the perspective of another person in order to predict their actions.

Video modeling. Video modeling is a mode of teaching that uses video recording and display equipment to provide a visual model of the targeted behavior or skill. Types of video modeling include basic video modeling, video self-modeling, point-of-view video modeling, and video prompting. (Evidence-based Practice and Autism in the Schools, p. 50 – 51);

Virtual Environments. Technology that provides a method of role-playing in the safety of a computer environment. Performing a task in a virtual environment may aid performance in everyday life-generalization and retention (Parsons et al, 2006)

Visual cue. A visual cue is a picture, graphic representation, or written word used to prompt a student regarding a rule, routine, task, or social response.

Next: Unit 3.3 Executive Function and Organization

Copyright © 2016 Columbia Regional Program