-

Setting up Home Instruction for Students with ASD

A How-to Guide for ParentsMANAGE CHALLENGING MOMENTS WITH POSITIVE BEHAVIOR SUPPORTS

For every parent and caregiver, we want you to know - we get it. Those who developed this resource know first hand that dealing with challenging behaviors is one of the most difficult and exhausting issues faced by families. As stated in the introduction, remember to take care of yourself while you are taking care of your family. Parents are working hard and doing the best they can.

Children with autism demonstrate challenging behaviors for a variety of reasons. We frequently say that "Behavior is Communication" because it is through their behavior that children are trying to tell us what they need. Often they are trying to get something they want, or to avoid something painful or unpleasant. They may be trying to get help or attention. Or they are seeking sensory input of some kind. Finding out why a child engages in a behavior is valuable information. We will share why and review several practical strategies that are effective in preventing challenging behaviors or in reducing the frequency and intensity of challenging behaviors.

HOW TO DO IT

Use prevention strategies. The best way to respond to a challenging behavior is to take steps to prevent it from occurring in the first place. If your child exhibits challenging behaviors when presented with and/or during schoolwork, consider the following:

➤ When presenting your child with a task, use preferred items or favorite topics to increase their interest level. For example, for a child who has a fascination with firetrucks perhaps we can find or modify a worksheet to integrate this special interest.

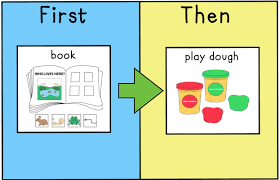

➤ When presenting your child with a task that you know they do not like, schedule a highly preferred activity right after the non-preferred activity. Present them together, "Time for reading, then you have have your Play-Doh set. First book, then Play-Doh." Note you may need to restrict access to Play-Doh so it is powerful when you need it to help motivate completion of a schoolwork task.

➤ Priming your child in advance for what is coming up can reduce challenging behaviors. For example, saying "In ten more minutes, it's time for reading." while pointing to the visual schedule. Then in a few minutes saying again, "In five more minutes, reading time." Many children with ASD like to go over their visual schedule in advance. When you go over it with them, you are reducing the likelyhood of problem behaviors when completing each activity.

➤ Priming is also very helpful when you have to make an unexpected change in routine or if you are introducing something new. For unexpected and new events, children with autism handle them better with advance warning.

➤ Having a child with autism engage in at least 10 to 20 minutes of exercise before giving them an academic task has been demonstrated to increase attention and engagement while reducing challenging behaviors. Bicycling, running, jumping on a indoor trampoline are good options - you could also build your own routine. The Exercise Buddy app (pictured below) was designed specifically for children with autism. Other apps are available to structure and support an exercise routine for your child.

➤ Offering choices is also a great way to reduce the likelihood of a challenging behavior. If your child has to read a book, then let them choose which one. If they have to complete some writing, let them choose what to write with.

➤ Reducing the type of amount of work your child is asked to do can help. For example, if you put a worksheet with 30 problems on it, they may have a big, negative reaction. If you present the worksheet with the first ten items circled and say, "It's time for math, but look you only have to do ten problems. You only have to do this top row, and then you can take a break." Alternately, if your child is struggling with work at a particular level, you can select something you know will be easier for them to at least get them in the routine of completing work.

➤ Providing your child with a fidget, sensory item, or small toy that they can manipulate while they are completing a schoolwork activity can reduce challenging behaviors. This is only an option if a child can hold onto the item without it interfering with the task they need to complete.

➤ Everything reviewed in the previous sections will help prevent challenging behaviors including setting up a structured workspace, using visual schedules, giving transition warnings, ensuring they are motivated and reinforced, and using clear, concise and concrete language.

Identify why a challenging behavior is occurring so that a replacement skill can be taught.

There are four main functions of a challenging behavior.

1. To get access to a preferred item or activity

2. To avoid or escape something that is unpleasent, scary, or even painful

3. To gain attention from an adult or other person (e.g., sibling, peer)

4. To provide a sensory experience that feels good

The first step in the process is to describe the behavior in specific terms. For example, "having a meltdown" is not specific. "Falls to the floor and screams" is much more specific.

The second step is to identify what happens right before the challenging behavior. What seems to trigger it? Is there a consistent pattern? For example, every time a child is asked to do a handwriting task they fall to the floor and scream.

Third, determine what happens after the challenging behavior. The child is asked to do handwriting. Then he falls to the floor and screams. After this challenging behavior, the child does not do the handwriting activity. So the consequence of the challenging behavior is the child avoids the handwriting task. This is an important discovery!

We have determined that the child is falling to the floor and screaming to escape handwriting tasks (that is the function of the behavior). It keeps happening because, from the child's experience, it works! It may not have been our intention, but the child is being reinforced when he falls to the floor and screams because he is escaping something he dislikes.

Identifying why a behavior occurs (i.e., the function) is extremely helpful because now we can think about a skill that we can teach to replace the falling to the floor and screaming. We need to identify a replacement that will give the child the exact same outcome. In other words, we need to teach a skill that will allow him to escape the writing task.

For some parents and educators, this is puzzling. Some will say, "We want the child to learn that he needs to do his work. He can't just get out of doing his work!" Remember that this child is falling to the floor and screaming when asked to do any writing. So we need to think about priorities. What is more important in the near term? Is it (a) doing his writing assignment or (b) learning how to avoid a task demand without resorting to falling to the floor and screaming? It is important for this child to learn how to escape a task demand in a socially appropriate manner. Plus, the child is not completing the writing task anyway and a power struggle to force the issue would likely make matters much worse.

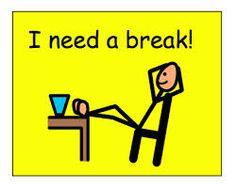

Since this child has developmentally appropriate spoken language, we decide to teach him to say, "I need a break" when he wants to avoid a writing task. We also provide a visual (left) that we can use to prompt him while he is learning. When he says "I need a break", we are going to reinforce him by allowing him to avoid the writing task and take a timed break. After his break, we'll ask him to come back to work. To ensure he learns the replacement skill, we must reinforce it. Remember the only way to increase a targeted skill is to reinforce it. If there is no reinforcement, there is no learning!

Since this child has developmentally appropriate spoken language, we decide to teach him to say, "I need a break" when he wants to avoid a writing task. We also provide a visual (left) that we can use to prompt him while he is learning. When he says "I need a break", we are going to reinforce him by allowing him to avoid the writing task and take a timed break. After his break, we'll ask him to come back to work. To ensure he learns the replacement skill, we must reinforce it. Remember the only way to increase a targeted skill is to reinforce it. If there is no reinforcement, there is no learning! Once the child is reliably asking for a break, we can gradually reintroduce the writing task and keep our expectations very basic. At first, perhaps we just want him to sit at the table for a moment - then we release him for a break. Next time, we want him to sit down and pick up a pencil. And that's enough; we provide a break. Then next time, we ask him to write his name. We gradually increase demands and reinforce his effort so that eventually he is able to complete writing assignments without difficulty.

Because the child can reliably request a break and because we are gradually increasing task demands, he is eventually going to be completing those writing assignments without difficulty. We often need to teach children with autism how to request a break (versus engaging in challenging behavior).

This video was produced by a parent working to teach her child how to request a break using a technique called video self-modeling. Video modeling involves capturing video of the child with autism or a peer or adult performing a targeted skill successfully and without prompts. Then the child watches the video to learn the skill.

Planned ignoring of challenging behaviors. In some situations, we plan to ignore a challenging behavior while teaching a replacement skill. For example, consider a child who screams when he wants adult attention or help. We know the function (to gain attention) so we decide to teach a replacement skill, saying "I need help." Next time the child screams, we ignore it and prompt, "Say 'I need help'". When the child says, "I need help" we rush over to provide adult attention (i.e., reinforce the replacement behavior).

Screaming worked for the child before. We need him to realize that it no longer works, but saying "I need help" does. At first, the child will probably scream more than he did before. This is because when a behavior that used to work suddenly stops working, people tend to increase use of the behavior until they realize it no longer works. In other words, it may get worse before it gets better but if we are consistent, it does get better!

Reinforce positive behaviors at every opportunity. As previously stated, the only way to increase a positive behavior is to reinforce it. If your child often struggles to get started with schoolwork, but does so without difficulty one day - don't take it for granted! Reinforce your child with something you are certain they like. Verbal praise may be limited in it's effectiveness for some children. In this case, we need to find something else we can deliver that the child will like (e.g., food, stickers, play, etc.) This is one way in which token boards and point systems (discussed in Tip 3) are so helpful because you can deliver reinforcement without disrupting what your child is doing.

Observe for triggers and use de-escalation strategies to avert meltdowns. When children with ASD are triggered by something, they will often show subtle signs of agitation before they engage in a challenging behavior. We call this the "rumbling stage" because they are building up toward a potential meltdown or rage episode. Autism researcher Brenda Smith-Myles calls these meltdowns and tantrums "neurological storms" because they come and go and are beyond the child's control.

During the rumbling stage, a child may show very subtle signs such as talking in a louder voice, tapping their foot or hand, or making little noises. For other children, it is more obvious they are triggered because they may grimace, make verbally agressive comments, start refusing to follow directions, and so forth. It is important to recognize when a child is triggered because we can usually de-escalate the child before it gets worse. How do we do that?

➤ Calmly remove the child from the situation to distract from whatever was causing the agitation. If you are in the kitchen and your child is triggered by something happening, distract him or her. Offer to go for a walk or do something your child enjoys. This strategy is all about distraction and taking the child out of the situation before they escalate.

➤ Provide calming support preferably with little or no words. If you can see your child is triggered, you probably know of something you can do or give him that will calm him. Perhaps it is handing him a fidget, or gently applying pressure to his or her shoulders. You can do this without words. Your actions say, "I can see something is starting to upset you. I want you to feel better."

➤ Bring attention to the visual schedule. Sometimes children get agitated because they do not know what is happening or how long it will be before a preferred activity. When you see your child is agitated, you can point to the schedule and say, "Look, after math you get to take a YouTube break. And then we'll have snack. Just ten more minutes of math, then video time." Predictable routines are calming to children with ASD so referencing their schedule may successfully de-escalate the situation.

➤ Just walk and don't talk. When children are in the rumbling stage, they may react negatively to any comment made by an adult. It is often helpful to simply say nothing at all. In fact, the more upset a child with ASD is the less we should say. Ironically, adults tend to talk more when children get upset, not less. This can actually cause the child to escalate.

➤ Provide access to a calming space. When your child is in the rumbling stage, you could allow them to go to a space in your home where they feel calm. Remember this is not a time out or punishment space - it is therapeutic. (Taking that approach would likely escalate matters quickly.) This should be a space where your child knows they can go to calm down and then come back when ready to work/learn.

In Review...

➤ Focus on prevention. This is where we should focus much of our time and efforts.

➤ Identify why a behavior is occurring, then teach and reinforce a replacement skill.

➤ Reinforce positive behaviors, try not to take them for granted.

➤ Recognize when your child is "rumbling" and use de-escalation strategies that will help your child calm.

Additional Resources

The Cycle of Tantrums, Rage, and Meltdowns in Children and Youth with High Functioning Autism

Challenging behaviour: children and teenagers with autism spectrum disorder

Setting up Home Instruction for Students with ASD

Setting up Home Instruction for Students with ASD

A How-to Guide for ParentsDeveloped by autism specialists at Columbia Regional Program

Email questions or feedback to crpweb@pps.net