-

Preparing Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder for Adulthood A Transition Toolkit for Educators

UNIT 3.6: Employment

Key Questions

- What is preparation for employment?

- Why prepare youth with ASD for employment?

- Do all youth with ASD need preparation for employment?

- When should I start preparing my student(s) with ASD for employment?

- What are the core components of preparation for employment?

- Who prepares youth with ASD for employment?

- How do I determine appropriate postsecondary career and employment goals with my student(s) with ASD?

- Why are work experiences necessary?

- Are there particular careers or jobs that are good for young adults with ASD?

- What types of skills should I teach my student(s) with ASD related to work?

- How do I teach my student(s) with ASD skills related to work?

- What supports are needed by youth and young adults with ASD in the workplace?

Appendices

- Appendix 3.6A: Online and Other Resources

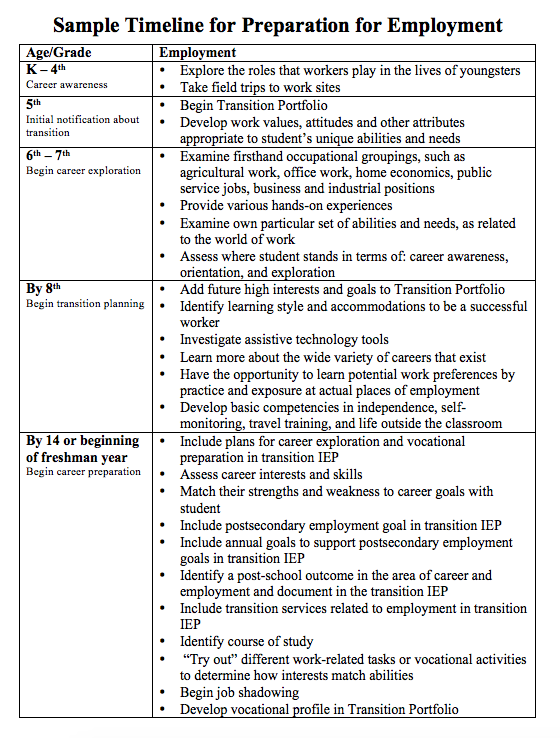

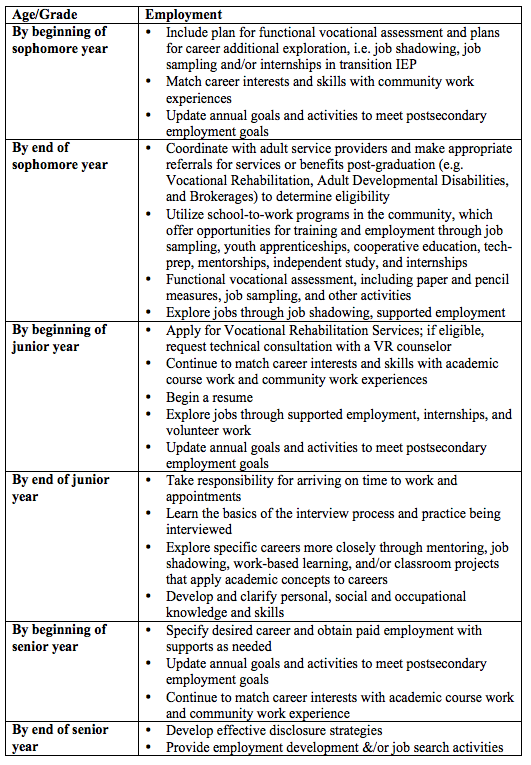

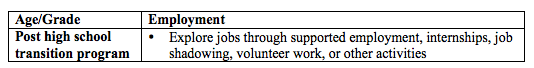

- Appendix 3.6B: Sample Timeline

- Appendix 3.6C: Forms and Checklists

- Appendix 3.6D: Glossary of Terms

by Phyllis Coyne

Preparing youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) for employment is a primary goal of K – 12 education. In order to assist educators to lead teams in developing an effective process to prepare students with ASD for employment, this unit of the toolkit provides basic answers to commonly asked questions and links to comprehensive resources about different aspects of career and vocational preparation.

Preparation for employment is a huge topic. Therefore, this unit is designed as a resource, in which you can return to sections, as you need more information or tools. You do not need to read this unit from beginning to end or in order. Feel free to print this unit for ease of reading or as an accessible reference. You will get the most from this unit by also using the online features. Links to questions, appendices and online resources are provided so that you can go directly to what is most relevant to you at the time.

Please be aware that the transition to successful, sustained employment for young adults with ASD also requires instruction in the other areas of the expanded core curriculum described in this toolkit. Information and resources on how to address the underlying characteristics of ASD, which are relevant to employment,

are provided in Unit 3.1: Communication, Unit 3.2: Social Skills, Unit 3.3: Executive Function/Organization, and Unit 3.4: Sensory Self-Regulation (You will need to scroll down to Preparing Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder for Adulthood). Information and resources to address other critical areas of the expanded core curriculum that are also important for employment are provided in Unit: 3.5: Self Determination, Unit 3.7: Postsecondary Education, and Unit 3.8: Independent Living. (You will need to scroll down to Preparing Youth with Autism Spectrum Disorder for Adulthood ).What is preparation for employment?

Preparation for employment is an individual and multi-year process of career awareness, career exploration, instruction in work behavior and skills, and work experience to enable students with disabilities, including those most affected by ASD, to transition from school to work. This process should lead toward paid work at the end of the school years when the entitlement to services under IDEA ends.

Why prepare youth with ASD for employment?

Work is a very important part of life with numerous benefits, including being participating and contributing members of one’s community and the local economy. Many individuals with ASD, including those with the most severe challenges, express an interest in working (Targett & Wehman, 2009). In fact, adults with ASD have said that finding a job would improve their lives more than anything else (Barnard, Harvey, Potter, & Prior, 2001). When they have the dignity of gainful employment, adults with ASD can contribute to essentials like housing, food, clothing and the supports and services needed in their lives.

IDEA 2004 clarifies the obligation to prepare students for employment both in its stated purpose and its regulations on postsecondary transition. The stated purpose of IDEA is “to ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education (FAPE) and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living” [6001(d)(1)(A)]. To this end, IDEA 2004 requires appropriate measurable postsecondary employment goals and annual IEP goals as part of transition IEPs, as well as coordinated transition services that will reasonably enable the student to meet his postsecondary employment goal.

Despite entitlements, such as IDEA, the current employment outcomes for adults with ASD are not encouraging. Data from the National Longitudinal Transition Study 2, a 10-year study of youth who received special education services, suggests that young adults with ASD are less likely to work than all but one other disability group (Newman et al., 2009). In a recent study of 4 counties in Oregon, 13% of young adults with ASD in the sample were employed in an integrated competitive employment setting and another 13% were in a supported employment setting (Coyne, Rake & Rood, 2010). In addition to high unemployment, adults with ASD, including those with Asperger Syndrome, experience underemployment, often lose jobs, and switch jobs frequently (Barnard, Harvey, Potter, & Prior, 2001; Howlin, 2000; Hurlbutt & Chalmers, 2004; Jennes-Coussens, Magill-Evans, & Koning, 2006; Müller, Schuler, Burton, & Yates, 2003; Newman et al., 2009). They do poorly even in comparison to others with disabilities. For instance, Cameto et al (2005) found that adults with ASD make the lowest hourly wage and worked the lowest number of hours per week of any disability. Many suffer from depression or anxiety disorders caused, or exacerbated, by their inability to find a good fit in the world of work.

Although the challenges of ASD are significant, it is possible for young adults with ASD to be employed and to live a life of quality where they actively participate in decisions that affect their lives. In fact, research and experience has shown that, with the right preparation and support, individuals with ASD can learn the necessary skills and utilize talents that lead to meaningful employment in a variety of community-based businesses and industries (Hillier, Campbell, Mastriani, Vreeburg, Kool, Tucks & Cherry, 2007; Howlin, Alcock & Burkin, 2005; Jennes-Coussens et al., 2006; Moore, 2006; Muller, Schuler, Burton, & Yates, 2003; Schall, Cortijo-Doval, Targett, & Wehman, 2006; Schaller & Yang, 2005; Targett & Wehman, 2009; Tsatsanis, 2003, Wehman, Targett & Young, 2007). Across the country young adults with ASD of divergent abilities are being successfully prepared for employment..

Various initiatives focus on such preparation. For instance, Oregon’s Employment First Initiative requires that employment in integrated work settings be the first and priority option explored in service planning for all working age adults with developmental disabilities, including ASD. One intent of these initiatives is less reliance on alternatives to employment (ATE) for adults with significant disabilities.

Preparation for employment during the school years is critical to improve outcomes for young adults with ASD and to meet the goals of Oregon’s Employment First Initiative. Research has found that, if young adults with ASD do not transition into employment after their education years, they have a 70% chance of not being gainfully employed throughout their lives (Roebuck, 2006). Career and vocational assessment, career development and work experience during the school years are key predictors of successful adult employment (National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center, 2007).

The significant potential of young adults with ASD to have meaningful employment and be contributing members of society needs to be developed. As Temple Grandin (2004) has pointed out, “Work is more than just a livelihood or paycheck; it is the key to a satisfying and productive life.”

Do all youth with ASD need preparation for employment?

Federal law requires career development and career-related experiences for all students and each state specifies how this will be accomplished. For instance, in Oregon, the Career Related Learning Standards was merged into the Essential Skills starting in 2012.

Additional regulations related to preparation for employment exist for students with disabilities. IDEA 2004 requires appropriate measurable postsecondary goals, measurable annual goals and a coordinated set of transition services and activities towards employment for all students with an IEP not later than the first IEP to be in effect when the child turns 16, or younger if determined appropriate by the IEP Team. All youth with ASD must be treated as viable candidates for employment. The ultimate goal is paid, community-based employment or self-employment for each student upon graduation, regardless of the severity of his or her disability.

With appropriate preparation and supports, even those most affected by ASD can have meaningful work, help support themselves, and contribute to their local communities. Young adults with ASD can be reliable, hard working employees that meet or exceed expectations. Some will be able to hold a job independently or with natural supports, while others will require support from qualified staff to retain a position.

Although it may be obvious that those most affected by ASD need preparation for employment, it is not always as obvious for students with Asperger Syndrome or high functioning autism. Average to high IQ does not guarantee obtaining or maintaining employment for adults with ASD. Without careful preparation and significant support, high functioning adults typically have only marginally better employment outcomes than those who are more severely affected by ASD. They need preparation for employment even if they are college bound, because after college they will be work bound. Although college may be a step towards career development, it usually does not provide other necessary skills and knowledge towards successful employment. All youth with ASD need preparation for employment while IDEA entitlements are in place.

When should I start preparing my student(s) with ASD for employment?

There are three answers to this question. One relates to federal and state mandates for career development of all students, another relates to the requirements of IDEA, and the third relates to the developmental process and ASD.

Federal and state laws recognize that career development is a long-term process. For instance, the Oregon Perkins IV State Plan’s vision for the future is to refine and enhance a connected and integrated education and workforce system that promotes a smooth and successful transition of all students from prekindergarten through grade 12 to postsecondary education, training and entrance into the workforce.

On the other had, IDEA 2004 requires that the transition planning process must begin “not later than the first IEP to be in effect when the child turns 16, or younger if determined appropriate by the IEP Team.” This means that IEP teams should start transition planning when the student is 15, so that they can assure that the planning and services have occurred on the IEP in effect when the student is 16. However, note that IDEA allows for transition planning to begin earlier when deemed appropriate by the IEP Team. In fact, research shows that preparation for the transition from secondary school to work must begin well before the completion of high school (National Alliance for Secondary Education and Transition, 2008).

Career Development Process And ASD

Because of the complexity of ASD, 15 years of age is too late to start preparation for employment. Activities towards preparing for employment need to start previous to the official transition planning age. There is strong support for starting early.

- As early as 1994, the Division on Career Development and Transition (DCDT) of the Council for Exceptional Children adopted a position that “The foundations for transition should be laid during the elementary and middle school years, guided by the broad concept of career development.” (Halpern, 1994).

- The Autism Guidebook for Washington State (2008) indicates that the process of preparing individuals with ASD for employment “starts at the earliest stages of special education (approximately 6 years of age)”.

- Baker (2005) suggests that career development is ongoing throughout one's lifetime.

Ideally, the process should incorporate a K-12 career development plan for all children to make certain that students are successfully progressing through career developmental stages and to determine whether students require assistance in reaching the goals associated with each stage. The Sample Timeline for Preparation for Employment in Appendix 3.6B provides an outline for what is recommended by various experts and organizations at each age.

There are compelling reasons to start preparing for employment in early elementary school for students with ASD. One is that this population does not naturally develop an interest in careers like other children do. Young children typically progress through a fantasy stage of career awareness in which they use their imagination to take on different career roles. However, children with ASD usually do not engage in this type of pretend play and do not appear to notice the jobs happening around them as they go to the store, doctor, or other places of community service (Frith, 2003). Structured activities or play routines may need to be established for children with ASD to experience these roles.

Later, as other children are becoming aware of their interests and different careers, students with ASD may only fixate on their own area of interest, unless they experience structured classroom and school jobs. They may not benefit as much as other students from field trips to places of work, job shadowing and speakers on occupations, because they may have difficulty understanding or focusing on relevant aspects of these experiences. By using work routines and work systems for classroom and school jobs, students with ASD can begin to gain work skills and focus on what is relevant.

During adolescence, most neurotypical youth begin to know their interests and abilities in more depth related to possible careers and become more aware of training required for careers. However, youth with ASD may continue to have limited awareness of the world of work unless they have structured activities to assist them. They are unlikely to know the options or understand how their skills and interests match career options unless they have had assistance progressing through career developmental stages and help reaching the goals associated with each stage. They need carefully guided career awareness and career exploration, through real world experiences in their areas of interest, to be able to take an active part in determining their own postsecondary goals for employment.

What are the core components of preparation for employment?

All youth need career awareness, career exploration, including self-knowledge of own abilities and interests, and career preparation for successful post school employment. These areas are even more important for students with ASD, because of the myriad of challenges they face in employment.

It is easy for educators and other transition team members to assume that at least some stages of career development have been attained by students with ASD. Unfortunately, this is often an unfounded supposition. In order to be able to identify and attain postsecondary goals for employment, youth and young adults with ASD require a range of career related activities, such as:

- Ongoing career and vocational assessment

- Career awareness/orientation

- Career exploration

- Measurable postsecondary goals for employment

- Course of study

- Transition services and activities, including community based career and work experience, instruction, needed supports, and interagency collaboration

Ongoing Career And Vocational Assessment

IDEA requires career/vocational assessment as integral to assisting youth to make informed choices and to set realistic goals for employment in adulthood. This includes assessment of the student’s preferences, interests, needs and strengths (PINS) related to employment. It may include assessment of transferrable skills, job specific skills, educational skills, interests, work values, aptitudes, functional living skills and career maturity. The answer to How do I determine appropriate postsecondary career and employment goals with my student(s) with ASD?, which appears later in this unit, provides more specific information on career and vocational assessment and Appendix 3.6A has links to a variety of assessments.

Career Awareness/Orientation

Benz et al. (1997) found that students who exited school with high career awareness skills were more likely to be engaged in post-school employment or education. Learning about the wide world of work needs to begin in elementary school, so that the student becomes aware of the world of work and different career options. By middle school and high school, it may include courses, programs, and activities that broaden the youth’s knowledge of careers, and allow for more informed postsecondary education and career choices.

Career Exploration

Career exploration involves examining firsthand a number of career options to help identify the student’s dreams and goals, interests and preferences and skills as well as support needs. Care must be taken to prime youth with ASD and to structure activities, job shadows, and site visits, in order for the youth to know what is most relevant and to overcome potential difficulties in learning by observation. Similar care must be taken in trying to familiarize higher functioning students with ASD with specific occupations by reading about them or talking with people working in those fields. With careful planning, exploration activities can provide useful information to help many youth with ASD to identify interests and preferences.

However, many other youth with ASD cannot learn through job shadows and site visits. Youth with ASD often need varied and multiple community-based work experiences to identify interests and postsecondary goals.

Another component of career exploration is examining their own particular set of abilities, characteristics and needs, as they relate to the world of work. This includes developing self-knowledge of preferences, learning style, strengths, personal attributes, values, skills, career interests and support needs related to employment. A number of links to instructional materials for self-knowledge for employment is provided in Appendix 3.6A. Since these instructional materials are not developed specifically for use with individuals with ASD, it is important to apply universal design principles and support the underlying characteristics of ASD. Unit 3.5: Self Determination provides more approaches and resources to assist in developing self-knowledge for youth and young adults with ASD. However, even with self-knowledge, many youth with ASD will need assistance to determine which jobs match up with their skills and interests.

Measurable Postsecondary Goals for Employment

A measurable postsecondary goal for employment must be based on age appropriate transition assessments, particularly career assessment and vocational evaluation. The individualized goal may be for employment in competitive, supported or sheltered employment. Excellent examples of a wide range of measurable postsecondary goals for employment are shown on the National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center (NSTTAC) website.

Youth with ASD need to make realistic career and employment decisions based on self-knowledge and awareness of career options, so that annual IEP goals that will reasonably enable the student to meet his postsecondary employment goals can be developed. When dreams for a career are not realistic, it is important to learn where the dream came from in order to help the student find alternatives and arrive at a compromise that suits the student’s interests, strengths, supports needs and preferences for type of work environment. Ultimately the decision is the student’s, but following a plan based on an unrealistic goal is not in the best interest of the student with ASD.

Course of Study

The transition IEP must identify the student's course of study. The intent is to make sure the courses in which the student enrolls helps him develop the knowledge and skills he will need to achieve his desired postsecondary outcomes. Some courses should be selected with a substantial experiential component, since many students with ASD learn best with hands on experiences. This includes paid or unpaid work experiences that are specifically linked to the content of the course of study and school credit.

There is strong evidence that broad career curricula that allow youth to select academic, career, and/or technical courses based on their career interests and goals results in improved postsecondary employment outcomes. Students with moderate to severe disabilities who participated in school-based programs that included career major (“sequence of courses based on occupational goal”), cooperative education (“combines academic and vocational studies with a job in a related field”), school-sponsored enterprise (“involves the production of goods or services by students for sale to or use by others”) and technical preparation (“a planned program of study with a defined career focus that links secondary and postsecondary education”) were 1.2 times more likely to be engaged in stable, full-time post-school employment with benefits, insurance, and paid sick days (Shandra & Hogan, 2008). Students with disabilities who participated in vocational education were 2 times more likely to be engaged in fulltime post-school employment (Baer et al., 2003; Harvey, 2002). Similarly, students with disabilities who received technology training were more than twice as likely to be employed (Leonard et al., 1999).

Transition Services and Activities

IDEA requires a coordinated set of services and activities that will reasonably enable students to meet their postsecondary goals. Although these services and activities are individualized, particular areas reflect best practice. These include:

- Community based career and work experience,

- Instruction and practice in “hard” skills,

- Instruction and practice in “soft” skills,

- Instruction and practice in job search skills,

- Needed supports,

- Interagency collaboration.

Community based career and work experience. Active, meaningful work experience aligned with student’s interests, strengths, skills and postsecondary employment goals prior to completing high school is a high evidence practice (National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center, 2007). These may include internships, apprenticeships, mentoring, paid and unpaid work, service learning, school-based enterprises, on-the-job training, and work study. In general, students who have community work experience prior to leaving school are significantly more likely to obtain and maintain employment (Carter, Owens, Swedeen, Trainor, Thompson, & Ditchman, 2009).

The following highlights the importance of three types of work experience.

- Structured Internships: Paid or unpaid internships can help young adults with ASD gain valuable work experience. For instance, students with disabilities who participated in the Bridges School to Work program in their last year of high school and completed the internship were four times more likely to be employed (Luecking & Fabian, 2000).

- Paid Work Experience: Paid work experience provides the student with the opportunity to learn, by practice and exposure, what his work preferences might be. Students of all disability categories who participated in 2 or more paid jobs during high school were more likely to be engaged in post-school employment. (Benz et al., 1997; Benz et al., 2000; Doren & Benz, 1998). Students of all disability categories who had a job at the time of high school exit were 5.1 times more likely to be engaged in post-school employment (Bullis et al., 1995; Rabren et al., 2002).

- Work Study (Jobs developed by the high school where the individual receives credit): Baer et al. (2003) found that students with disabilities who participated in work study were 2 times more likely to be engaged in full-time post school employment.

Instruction and practice in “hard” skills (job skills). Youth with ASD need instruction in job skills in real community settings. This is provided through the course of study and community work experience.

Instruction and practice in “soft” skills. “Soft” skills are functional independent living and work related skills that enable youth and young adults to survive and succeed in the real world. Adult outcomes for individuals with ASD can, at least in part, be seen as a function of “soft” skills (Mazefsky, Williams, & Minshew, 2008). Over 80% of jobs lost by young adults with ASD are a result of poor “soft” skills, especially poor social skills. Some examples of “soft” skills and units in this toolkit that address them are:

- Communication (Unit 3.1)

- Social skills (Unit 3.2)

- Problem-solving (Unit 3.3)

- Self advocacy, including disclosure (Unit 3.5)

- Independent living skills (Unit 3.8)

- Work behavior, such as attendance, punctuality, and follow through

Since youth with ASD require systematic instruction in those skills and behaviors, a good transition plan needs to identify goals for improving specific “soft” skills based on age appropriate transition assessment. White and Weiner (2004) found that students with severe disabilities who participated in community-based training which involved instruction in non-school, natural environments focused on development of social skills, domestic skills, accessing public transportation, and on-the-job training were more likely to be engaged in post-school employment. Although some instruction can be classroom-based, instruction in “soft” skills must also be provided through work experiences that are part of the transition plan.

Instruction and practice in job search skills. Youth with ASD need instruction in the many steps that happen before and while applying for a job. Youth with ASD benefit from multiple opportunities to develop traditional job preparation skills, such as finding appropriate open positions, completing job applications, writing resumes, developing work portfolio, interviewing, and follow up, through job-readiness curricula and training that applies principles of universal design and when any additional strategies and supports are added. Benz et al. (1997) found that students who exited school with high job search skills were more likely to be engaged in post-school employment.

Interviewing is often very difficult for youth and young adults with ASD. Some of these young people will need approaches to getting a job that minimize the need to interview and interact to compensate for the social challenges associated with ASD. One approach is to develop a career or work portfolio, which shows results of work and highlights achievements, to sell the youth’s skills without an interview. A complementary approach is to obtain a job through a family/friend network.

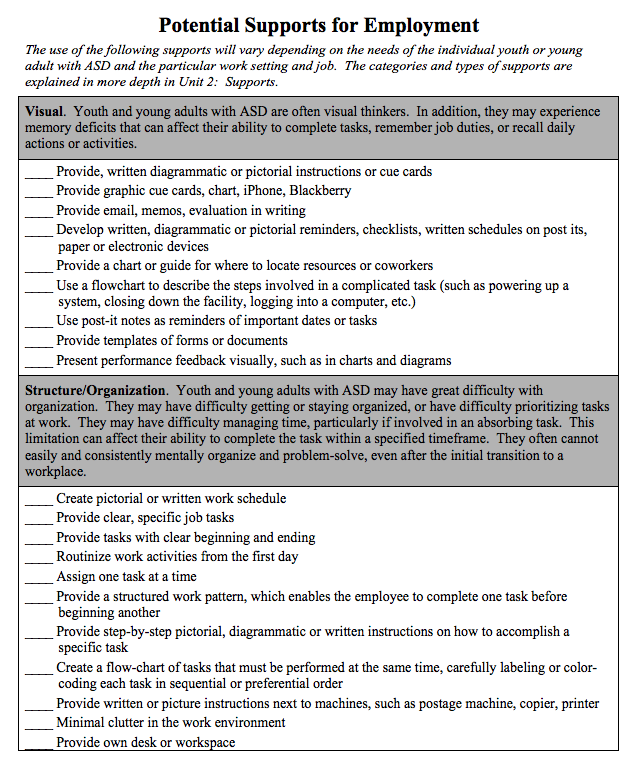

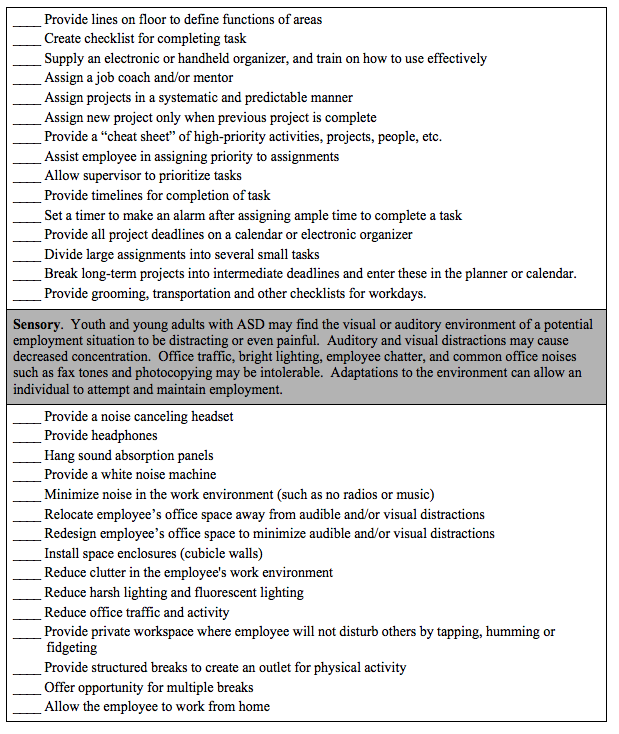

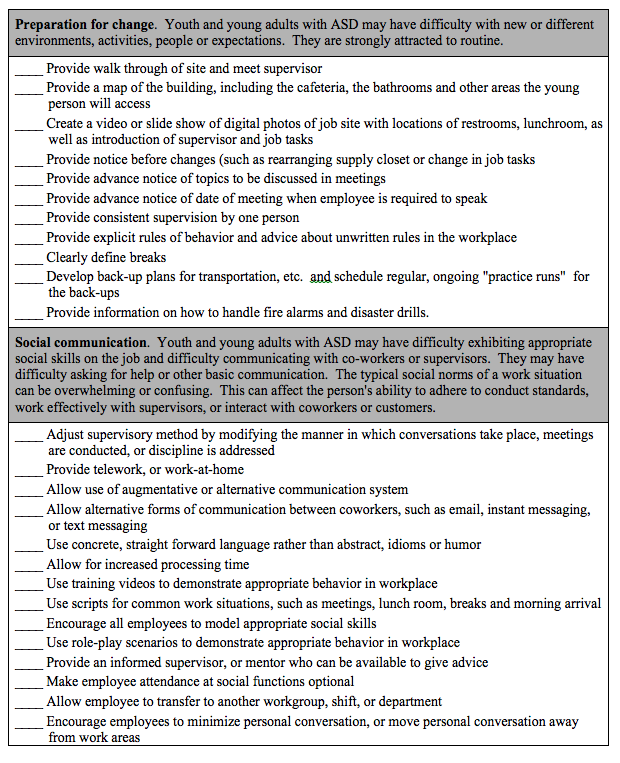

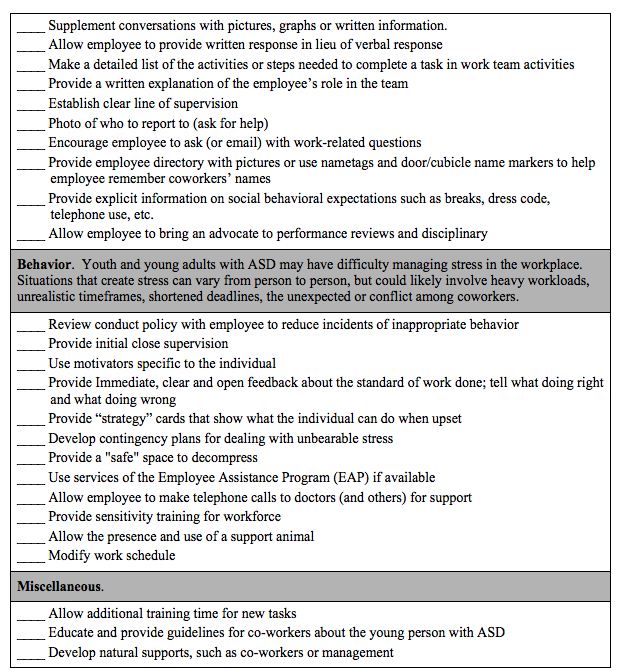

Provision of Needed Supports. Youth must be able to access, accept, and use individually needed supports and accommodations for work experiences and employment. Further information and resources for supports is provided in this unit under the answer to What supports are needed by youth and young adults with ASD in the workplace? and in Appendix 3.6A under Supports for Employment and Potential Supports for Employment in Appendix 3.6C.

Interagency Collaboration. Linkages to individually determined adult support services, such as Vocational Rehabilitation, Workforce Investment, Social Security Work Incentives, brokerages, and employment vendors, prior to graduation is a high evidence practice for the education and employment success of all youth, including those with ASD (National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center, 2007). For example, students of all disability categories who received assistance from 3 to 6 community-based agencies (as compared to students with assistance from 0 to 2 agencies) were more likely to be engaged in post-school employment or education (Bullis et al., 1995).

Schools are responsible for inviting representatives from outside agencies. In addition, the Interagency Transition Subcommittee of the Oregon Autism Commission (2010) recommended that students and their families leave school services with an Exit Package that facilitates entry into adult services, or other postsecondary programs, including the most recent testing information, vocational evaluation, present level of performance, etc.

Given the often complex and long-term needs of many individuals with ASD, the development and maintenance of systems of interagency cooperation to best provide for a continuity of services after transition is vital. Formal interagency agreements and action plans, that identify which services will be provided by each agency, which students will receive services, and when services will be initiated, should be developed between school and community agencies.

Who prepares youth with ASD for employment?

The transition team, in collaboration with adult service agencies, has the unique role of identifying interests and abilities, developing skills, facilitating career development, helping to identify postsecondary employment goals and preparing youth with ASD to attain their postsecondary employment goals. In the process many individuals may be involved in preparing the young person for employment. This may include, but is not limited to:

- Parents or guardians and other interested family members

- Special education teacher(s)

- General education teacher(s)

- Vocational educator(s)

- School district representative

- Transition specialist at the school

- Vocational specialist at the school

- Vocational rehabilitation counselor from the community

- Guidance counselor

- Speech and language pathologist

- ASD specialist

- Occupational therapist

- School psychologist

- Behavior specialist

- Job development specialist

- Job coach

- Friends or people from the community who know the young person well

- And eventually, the employer.

Four key roles in assisting youth with ASD to prepare for employment are:

- Parents/guardians and other family members,

- Transition specialist or vocational specialist,

- Job development specialist, and

- Rehabilitation counselor

Parents/guardians and other family members play crucial roles not only in career preparation, but also in actual job search efforts. They often provide:

- Ideas about the type of work an individual likes and is able to do,

- Suggestions about where to look for a job,

- Connections in the community, and

- Assistance with transportation. (TATRA Project, 1996; NICHY, 1999).

Transition Specialist Or Vocational Specialist

A transition specialist or vocational specialist may become involved through the public school system when transition planning begins for a student with ASD. This specialist can help the student through activities, such as:

- Working with the student to identify preferences and goals;

- Setting up opportunities for the student (or a group of students) to learn about different careers through such activities as watching movies about careers, job shadowing, visiting different job environments, and hands-on activities that allow the student(s) to try out a job or aspects of a job;

- Looking at what skills the student presently has and what skills he will need in the adult world;

- Recommending coursework that the student should take throughout the remainder of high school to prepare for adult living (recreation, employment, postsecondary education, independent living);

- Identifying what job supports the student needs;

- Helping the student assemble a portfolio of job experiences, resumes, work recommendations, and the like; and

- Making connections with the adult service system (NICHY, 1999).

Job Development Specialist

A job development specialist usually works for a school system or an adult service provider agency such as the vocational rehabilitation agency or brokerage. As the job title suggests, the chief activity of such a specialist is finding jobs for people with disabilities. The job development specialist will usually approach an employer to see what positions may be available that match the prospective employee’s abilities and preferences or to carve job for an individual with a disability. The job developer and a job coach may divide the following activities:

- Placing the person on the job;

- Training the employee on job tasks and appropriate workplace behavior;

- Talking with supervisor(s) and coworkers about disability awareness;

- Providing long-term support to the employee on the job; and

- Helping to promote interaction between the employee and his or her co-workers (PACER Center, 1998; NICHY, 1999).

Rehabilitation Counselor

Rehabilitation counselors can be involved in a student’s transition planning while the student is still in school. This professional usually works for the state’s vocational rehabilitation (VR) agency, helping people with disabilities prepare for and find employment. State vocational rehabilitation agencies are one of the most important sources of employment services for individuals with ASD and other disabilities. For students who are eligible for VR, a wide variety of services are available, including:

- Evaluation of the person’s interests, capabilities, and limitations;

- Job training;

- Transportation;

- Aids and devices;

- Job placement;

- And job follow-up (NICHY, 1999).

Members from VR, other adult service organizations and local school districts can combine resources in creative ways when they talk together about mutual goals for students.

How do I determine appropriate postsecondary career and employment goals with my student(s) with ASD?

Selecting a career or job and preparing for work present youth with ASD and their transition team with the challenge of having to make complex decisions. Age appropriate transition assessment is necessary to help determine fitting postsecondary employment goals and transition services. Unit 1 provides information and assessment tools for age appropriate transition assessments in general.

A major purpose of age appropriate transition assessment and transition services is to help the youth with ASD to identify the types of careers, jobs and work environments that are a good fit for him. A variety of assessment and instructional material for this purpose, which are not designed specifically for young people with ASD, can found in Appendix 3.6A. A checklist designed specifically to assist youth and young adults with ASD in identifying their personal work style and match for potential employment can be found in Appendix A of Transition to Adulthood: Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders.

Since success in employment for young people with ASD is dependent on an array of conditions of employment and a variety of skills beyond work skills, appropriate and meaningful planning for employment must utilize and build on the holistic information from other areas of the age appropriate transition assessment. Assessment of self-determination (Unit 3.5) and independent living (Unit 3.8) yields valuable information about the youth that further informs goals. Assessment of the underlying characteristics of ASD is essential to develop appropriate goals and to chose instructional strategies.

Assessment of Traits Related to ASD

Other units of this toolkit supply important information and resources for assessment related to the underlying characteristics of ASD. Unit 3.1 – 3.4 offers substantive information and assessment tools for the underlying characteristics of ASD, including communication, social/interpersonal, organization/executive function and sensory self-regulation. These unique traits are relevant to determining postsecondary employment goals and transition services, such as training, support and supervision.

Career and Vocational Assessment

Comprehensive career and vocational assessments are also critical to youth with ASD and their transition team’s ability to make the best decisions and choices about postsecondary employment goals and transition services. These assessments should be carefully planned, involve a team of professionals from school and community agencies, such as career centers and Department of Vocational Rehabilitation, and be integrated within K–12 career planning process.

Career and vocational assessment formally and informally measures and documents the youth's interests, values, temperament, aptitudes, skills, behaviors, awareness, physical capacities, and learning style related to career and work, while simultaneously providing youth with multiple opportunities to discover their own career preferences, needs, strengths, abilities and interests. The results will assist the youth and his transition team to match his abilities, interests and other attributes to suitable goals and services, including training and support services.

During career and vocational assessment, the student with ASD and his transition team has opportunities to explore career interests and abilities through a variety of assessment techniques. These techniques may include interest and aptitude testing, interviews, rating scales, observations in various settings, performance tests, work samples and situational assessment in as naturalistic a setting as possible. Appendix 3.6A contains links under Assessment to comprehensive guides on career and vocational transition assessment and links to free assessments for use by the individual.

Considerations For Assessment of Youth with ASD

Although all the techniques and assessments are potentially useful, they will yield valid results only if professionals can obtain a response from the student that accurately reflects the student’s interests, skills and abilities in the area assessed. The transition team must discuss the best way to elicit a productive response from the youth with ASD that takes into consideration the unique characteristics of the youth with ASD. In addition, professionals assessing students with ASD should have a firm understanding of ASD in order to produce and interpret valid assessment results. The following information can assist in understanding characteristics of ASD in relationship to career and vocational assessment.

Formal assessment. Caution must be exercised in the use of and interpretation of results from the many commercially available, formal tools that assess career maturity, preferences, interests, aptitude, learning styles, specific vocational skills and potential or abilities to perform in jobs within specific career fields. Youth with ASD may not perform well on formal, standardized assessments due to their complex neurological differences. Performance on the test may more accurately reflect how the youth performs in a new situation, with new materials, and/or with a new person than what the test intended to assess. In addition, several hours of traditional assessment or a checklist of vocational skills often misses the youth’s unique and most important strengths and skills that may be suited for a specific “niche” and could lead to successful supported or competitive employment. Consequently, the standardized scores from such testing cannot be the sole basis to make decisions about a youth’s ability to work in the competitive labor market. Further assessment in “real” environments needs to be done. In general, descriptive reports that consider functionality and informal assessment results are more helpful than “stand alone” scores.

However, steps can be taken to get the most valid results from formal assessment, such as universal design for career and vocational assessment that is tailored to accommodate and meet the needs of all students. Formal career and vocational assessment should:

- be examined to ensure the chosen test is appropriate for the age, grade level and reading ability of the youth being assessed;

- offer a choice of methods and techniques and use a variety of methods to achieve results;

- be created to be straightforward and predictable;

- utilize actual artifacts and samples that illustrate expectations;

- provide multiple representations that include digital materials, models, and hands-on demonstrations;

- be designed to anticipate variation in student learning and, if repeated enough, performance;

- utilize structured directions and finite steps;

- use adjustable spans of time and shorter test periods;

- use student’s communication preferences/mode;

- begin by explaining what will happen, communicate in a medium comfortable to the individual, and provide safe environments;

- be designed to provide results that are communicated in multiple ways that can be accessed and understood by the individual and others who need to be informed; and

- be designed to include recommendations in results about future universally-designed learning, assessment, and employment that will promote success in educational, career, vocational, and employment endeavors.

Many students with ASD will need creative approaches to assessment beyond universal design. Some of these include:

- Use tests that are sensitive enough to reflect scattered abilities.

- Ask in advance about sensory issues, communication mode, signs of frustration, over stimulation, etc., motivators.

- Expose the student to the setting and evaluator(s) previous to assessment.

- Provide advance notice to the prior to testing.

- Utilize sensory motor preparation for optimal level of alertness.

- Provide quiet, tidy, environment with moderate light.

- Avoid expressions, jokes, innuendos, indirect messages and "hints".

- Use concrete language.

- Supplement verbal information with visuals – schedules, outlines, pictures, written summaries.

- Allow extended quiet time for processing and thinking.

- Focus less on language and more on an individual’s ability/performance.

- Cue or prompt the student in a familiar manner when asking the student to perform a task to determine prompt dependence.

- Use natural methods of evaluation and assessment, such as observation, as much as possible.

Other units of this toolkit provide information and resources on supporting youth with ASD to optimize valid assessment results. For instance, Unit 1 discusses special considerations in assessment for youth with ASD that also applies to career and vocational assessment. A manual from the Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence, Transition to Adulthood: Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders, provides characteristics, implications and strategies for assessment in Section 2: Age Appropriate Transition Assessment.

Interest inventories. A variety of standardized assessment inventories and tools are available to assist youth in recognizing their predominant interests and preferences. Because these surveys, when used properly, can help some youth with ASD understand how their interests have direct application to making good academic and career choices, links to interest inventories, as well as career-interest and job-match software programs sponsored in the public domain by Federal agencies such as the Department of Labor (DOL) are provided in Appendix 3.6A.

However, the use of and results of interest inventories, in which youth with ASD provide answers, must be considered carefully and planned creatively. Numerous vocational interest inventories and tests ask individuals to imagine themselves in situations. Many youth with ASD have limited experience in the world of work and tend to have difficulty imagining themselves in different situations (Attwood, 2006; Siegel, 2003). If a student with ASD is not able to imagine himself in these situations, the responses he gives will not yield accurate information. Even pictorial, reading free and video interest inventories do not necessarily provide the type of information needed by a student with ASD. Because of the nature of ASD, the student may base answers on irrelevant detail(s) of the visual representation of the career or job. Therefore, participating in a tryout of that job can most effectively help youth with ASD understand a job.

Informal Assessment

Informal assessment is often more informative than formal assessments. Some examples of informal assessment include questionnaires, checklists, interviews, observations in various situations, and job tryouts. Information accumulated and documented by observing the student as he participates in various academic and work experiences, talking with the student and those who know him well about interests, abilities and challenges, and setting up experiences that will allow the student to try something that he thinks may be of interest provides a wealth of informal data. Situational assessment and environmental assessment are tow particularly useful types of informal assessment.

Situational assessment. Situational assessment, also referred to as direct observation, measures an individual’s interests, abilities, and work habits in actual places of employment, such as a job tryout or unpaid work experience. It, additionally, provides multiple opportunities to try essential job functions of different jobs that help youth determine if they really enjoy the work, if their interests match their abilities and if they have the stamina to meet work requirements.

The process of situational assessment usually involves defining specific tasks, teaching a student to perform them, and then observing the student while completing them. The information from situational assessment typically includes task analytic data of steps in the core job duties, work behaviors (e.g., on-task, following directions, getting along with co-workers), and affective information (e.g., student is happy, excited, frustrated, or bored).

Situational assessments are one of the best ways to assess a student’s interest in a particular job and his skills to perform the job. Ongoing situational assessments provide a basis to reassess interests and capabilities based on real-world experiences and to redefine postsecondary goals, as necessary.

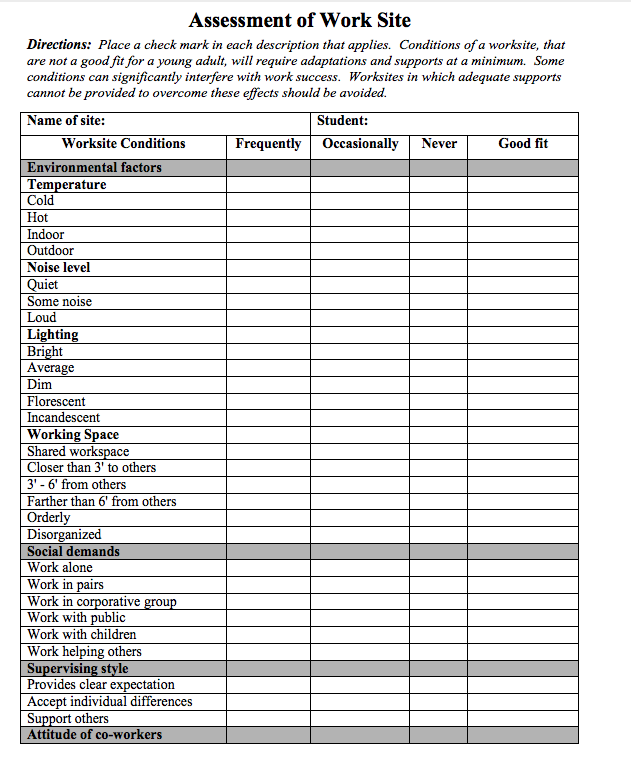

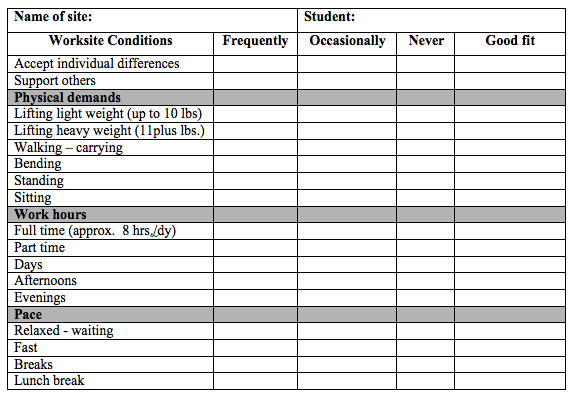

Environmental assessment. Another excellent means for gathering useful information is environmental or ecological assessment. This type of assessment examines a variety of factors that may contribute significantly to the success of an individual at work. Some of the factors assessed may include, but are not limited to:

- Availability of close supervision;

- Style of supervision (i.e., casual vs. autocratic);

- Building structures and layout of the working environment;

- Flow of product or service processes;

- Effects of formal and informal rules;

- Social interaction demands of others (i.e., co-workers, customers);

- Sensory stimuli, such as noise, motion, temperature, air quality, etc.;

- Work schedules and time requirements;

- Opportunities for independence and decision-making;

- Performance expectations of authorities; and

- Opportunities for self-correction.

If a student expresses interest in a specific type of job, an environmental job analysis could be conducted comparing requirements of the job to the student’s skills (Griffin & Sherron, 1996). This approach is particularly valuable for students with ASD, because they often express interest in a specific career that other assessment information indicates is not possible for them. If the environment is appropriate and liked by the student, other jobs in that environment should be evaluated with the skills of the student in mind. If an apparent match is found, the student should have an opportunity to participate in a situational assessment. Unit 3 of this toolkit provides a description of the steps of an environmental assessment and a sample form.

An additional outcome of environmental assessment can be to identify types of accommodations that could be provided to help a student perform the necessary functions of a particular job (e.g., job restructuring, modifying equipment, acquiring an adaptive device, re-organizing the work space, hiring a personal assistant) (Griffin & Sherron, 1996; Test, Aspel, & Everson, 2006).

Why are work experiences necessary?

The most effective way for student with ASD to learn about the best match for him in career, jobs and work environments is through multiple work experiences. These work experiences, additionally, provide the opportunity to develop the skills necessary to keep and hold a job, develop a sense of which types of jobs and job conditions are best for them and increase their level of community involvement. Students will gain the most self-knowledge and work competencies if work experiences are not just generic, but reflect their interests, strengths and needs. These work opportunities should be consistent with the student’s career plan and postsecondary goals.

For the majority of youth and young adults with ASD, their motivation to work will be directly related to the extent to which they enjoy the work they are being asked to do. Rather than being motivated by money, the degree of job match can be the critical factor between employee and employer satisfaction. It is critical to expand from a focus solely on skill requirements to a consideration of a match with interests and strengths of the individual, and features of the workplace, such as physical environment, supervisory style and attitudes. A good job fit makes for a more satisfied employee, which results not only in increased self-esteem but also productivity.

Generally, as students move through work experiences, they get closer and closer to a good job and career match. Members of the transition team need to carefully plan and develop these work experiences. These experiences may be typical jobs in the community or may be customized positions that are negotiated to meet the need of employers and create a good match with the young adult’s unique skill set. In addition to knowing the individual student, understanding some of the typical strengths and needs of youth and young adults ASD can be useful in determining work experiences now and paid work in the future.

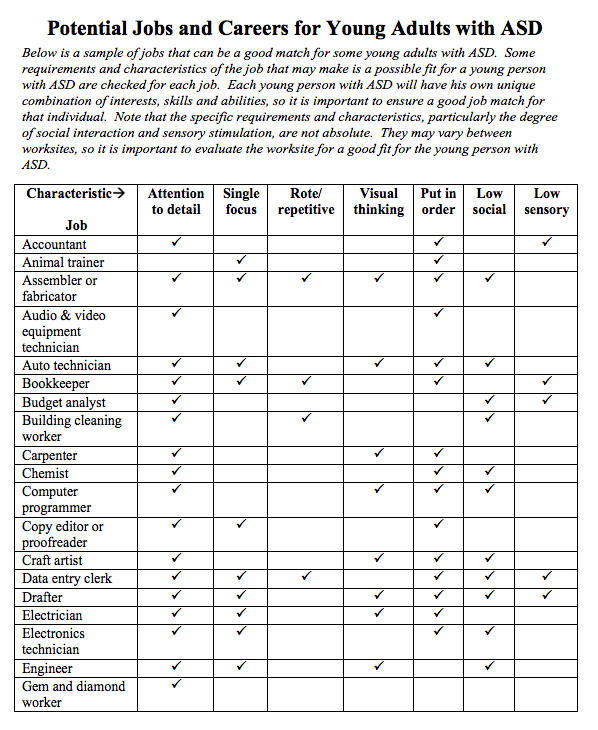

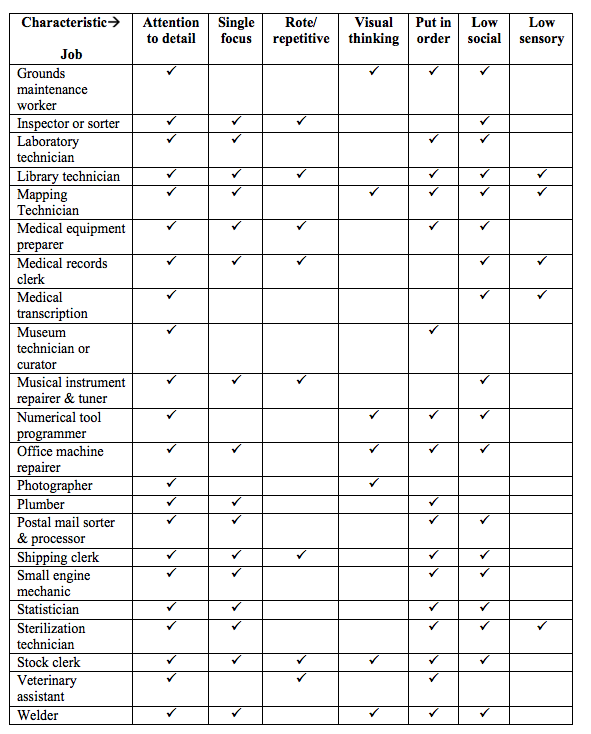

Are there particular careers or jobs that are good for young adults with ASD?

As a group young adults with ASD can successfully be employed in a myriad of careers and jobs. However, each individual has unique interests, preferences, strengths and needs that shape the types of careers, jobs and work environment that are a good fit for him and will potentiate a satisfying and successful experience for him and his employer.

Strengths of Young People with ASD in Work

It is important to avoid jobs that emphasize weaknesses and find ones that utilize strengths. Many youth and young adults with ASD have similar positive characteristics that are valued by employers. A young person with ASD may have any combination of the following traits:

- Honesty

- Dependability

- Attention to detail

- Strong memory for figures and facts that they are interested in

- Vast knowledge of specialized fields

- Ability to order systems, such as matching, collating, designing, computers, certain types of machines

- Accuracy in visual perception

- Strong visual memory of what they have seen

- Unique talents

- Working on a task until it is completed

- Focus on a limited number of things for extended periods of time

- Unique perspective

In addition to the desirable traits for employment listed above, youth and young adults with ASD show proficient and sometimes even superior skills in “systemizing” (Baron-Cohen, 2003). Systemizing is the drive to analyze or build systems in order to understand and predict the system’s behavior and its underlying rules and regularities. Skill in systemizing lends itself to the use of systems-oriented visual technologies, science, geography, electronics, music, and how things work, in general.

For more information about the positive aspects of ASD in the workplace, read the short article, Autistic Traits: A Plus for Many Careers (Rudy, 2006, updated 2015).

Using Interests

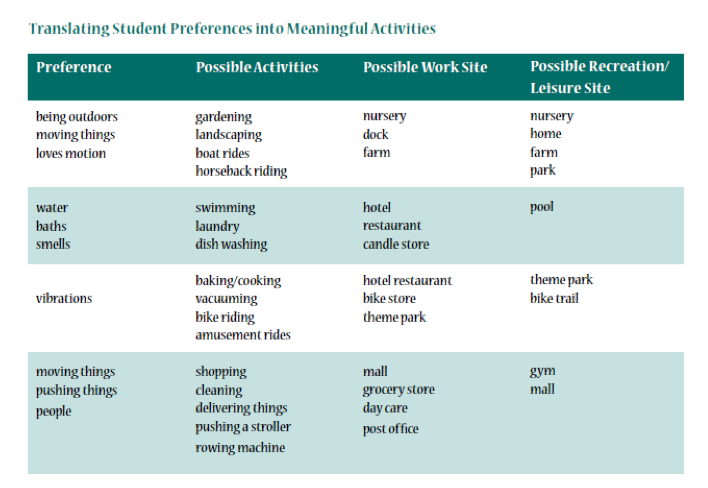

The transition team needs to explore the student’s interests with him. Using interests and passions are an important consideration in the choice of jobs and careers. The following chart shows how interests can be combined to generate some job and career possibilities.

Source: Virginia Department of Education (2010). Autism Spectrum Disorders and the Transition to Adulthood.

Often a youth with ASD will have a topic or activity of intense interest, in which they are very motivated to invest a lot of their time and energy in. Success for young people with ASD is more likely if they are able to work in an area related to their special interests or talents. Some develop expertise in a particular field because of extensive study or the serious pursuit of a hobby

Special interests and skills of students with ASD, even those that seem unusual, can contribute to successful employment with a good job match that builds on these interests. For instance, Cameron was extremely interested in fire alarms from the time he was very young. In elementary school, taking a break to look at fire alarms was utilized as a reinforcer for completing designated work. In secondary school, he enjoyed looking at and drawing diagrams of the interior of fire alarms. During his transition program, his special interest was utilized in a work experience as a fire alarm inspector where his knowledge and intense interest in fire alarms was appreciated.

Grandin (2004) suggests that career exploration by youth and young adults with ASD begin with matching their passions and notes that “many successful people with ASD have turned an old fixation into the basis of a career.” This can sometimes be accomplished through a restructuring of job duties or tasks so that a youth with ASD, who cannot perform the entire job or the whole range of skills required, can successfully perform job functions of high interest. Grandin mentions that the “freelance route” has enabled people with ASD to be successful and exploit their talent area (e.g., perfect pitch, mechanical ability, artistic talent, etc.) (Grandin & Duffy, 2004.). Such customized employment has been advanced and supported through the Department of Labor and is providing new meaning to the life of young adults severely impacted with ASD, who previously would have been placed in sheltered employment. (Romano, 2009).

Features of the Workplace

For many young people with ASD, the type of work environment is more important than even the specific type of work. Work must fit the young person’s temperament, such as preference of working with data, people, or things; preference for indoor vs. outdoor work; working alone or with people.

The match between the youth or young adult and a particular job’s social, physical, navigation, and production requirements, as well as environmental factors, must be considered. Some environmental conditions are more likely than others to promote challenging behaviors. For example, settings that produce high levels of sensory stimulation may tend to increase discomfort and anxiety in some youth with ASD. Some employers and work settings may be more tolerant of unusual behaviors exhibited by youth with ASD.

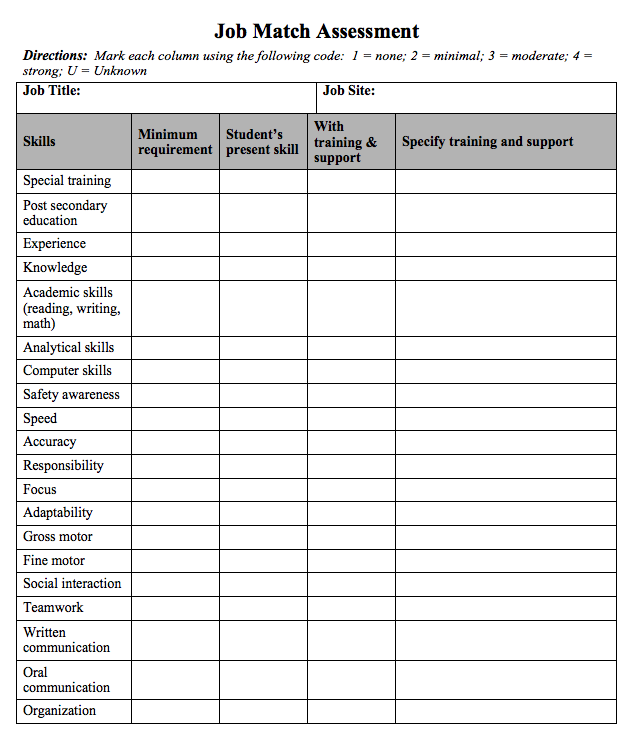

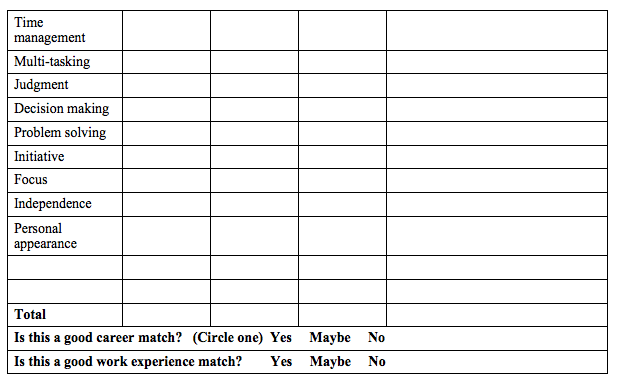

Two formats are included in Appendix 3.6C to help determine job match. The Career and Job Match Assessment in Appendix 3.6C provides a format to determine and record minimum skills for specific jobs, the student’s present skill level and potential skill level with training and support, and needed training and support. The Potential Jobs and Careers for Young Adults with ASD, also in Appendix 3.6C, provides a sample of jobs and careers with requirements and characteristics of the job that may make is a possible match for an individual with ASD.

There are general characteristics of a workplace or job role that tend to be a good match for young adults with ASD. These include, but are not limited to:

- Quiet

- Stable and predictable

- Consistency and repetition with little variation from day to day

- No excessive sensory stimulation

- Allows for sensory retreats

- Few distractions or interruptions

- Low social demands

- No direct contact with outsiders

- Explicit supervision from an informed, compassionate boss

- Explicit, written rules and expectations regarding such things as breaks, dress code, telephone use, etc.

- Unconventional behavior and thinking is accepted or valued

- Special, more technical or concrete skill or interest is employed

- Strengths utilized (e.g., visual-spatial, attention to detail, memory for facts or figures)

- Visually-based tasks

- Relatively low time or productivity pressures

- Accuracy more important than speed

- Built-in structure to job duties and/or work environment

- Logical approach to tasks

- Clearly defined work tasks, specification and expectations

- Work results measured quantitatively and absolutely

Few workplaces or job roles meet all these conditions. The importance of each characteristic will vary according to the traits of individuals. Supports, such as those listed in Potential SUpports for Employment in Appendix 3.6C, can accommodate for the lack of some of these characteristics. However, workplaces and jobs that have the characteristics most important to the individual young adult with ASD will result in the highest job satisfaction and success.

What types of skills should I teach my student(s) with ASD related to work?

The specific skills to be taught will depend on the needs of the individual student with ASD. However, youth with ASD require systematic, carefully planned direct instruction in not only the actual skills needed for a particular career or job, but also for a variety of other skills that are necessary to find and maintain employment. Learning the job itself (“hard” skills) is typically easier for youth with ASD than the “soft” skills, such as accepting directions from supervisors, working with other people, and dressing appropriately, as well as knowing how and when to chat or joke with coworkers, what to do during breaks, and how to ask for help as needed. Mistakes as a result of poor “soft” skills are most often the reason young people with ASD lose their job. Other characteristics of ASD can also cause difficulties in maintaining a job. For instance, even the most intelligent young person with ASD may have significant difficulties with organizational aspects of their jobs, such as showing up on time, time management, accepting changes in routine, and keeping work materials organized.

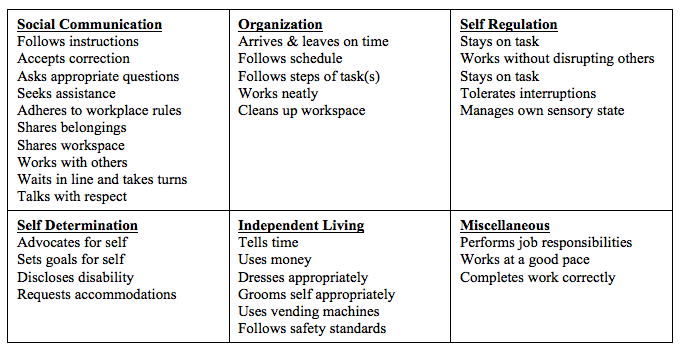

TABLE: Important “soft skills" for employment.

Youth with ASD usually need instruction in communication, social skills, organization, and self-regulation as it relates to the workplace even though they have the skills and abilities to perform the requirements of the job. Unit 3.1 – 3.4 of this toolkit provide advice and resources to help you provide instruction in these areas. Skills for self-determination (Unit 3.5) and independent living (Unit 3.8), such as transportation and money use, are also integral to success in employment.

How do I teach my student(s) with ASD skills related to work?

The instructional methods and content will depend on the needs of the individual student with ASD and goals of instruction. Understanding both the job and the characteristics of ASD is important in effective instruction. The following steps will go a long way in creating a positive work experience.

- Carefully plan instruction ahead of time. Youth and young adults with ASD are often rigid and prefer routines. Once they have something in their head it may be difficult to change it. If they are not taught the right thing at the right time, it may be necessary to go through the difficult process of unlearning and relearning.

- Spend time at a job site before the student begins the job in order to understand the requirements of the job itself and the necessary “soft” skills.

- Know the steps of the work tasks before you teach them. Clarify with the employer if everything you intend to teach is correct. Coworkers may have helpful tricks or tips to doing the work the most efficiently.

- Know about instruction and the issues of cue dependence and motivation for youth with ASD. Staff who use the side-by-side method can actually build themselves into a youth with ASD's routine and not be able to fade out once they are built into that routine.

- Know about evidence-based practices for youth with ASD.

Evidence-Based Strategies

For the best postschool outcomes in employment, staff providing instruction must be well versed in evidence-based strategies for youth with ASD. This is not as daunting as it sounds, because there are some excellent resources to enable teachers and other professionals to implement these strategies. For instance, the Autism Internet Modules (AIM) provides free online training on evidence-based strategies specific to “Autism in the Workplace”, which includes:

- Antecedent-Based Interventions (ABI)

- Computer-Aided Instruction

- Differential Reinforcement

- Extinction

- Home Base

- Overview of Social Skills Functioning and Programming

- Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS)

- Preparing Individuals for Employment

- Reinforcement

- Response Interruption/Redirection

- Rules and Routines

- Self-Management

- Social Narratives

- Speech Generating Devices (SGD)

- Structured Teaching

- Structured Work Systems and Activity Organization

- Task Analysis

- Time Delay

- Transitioning Between Activities

- Visual Supports

Another excellent resource to learn about effective strategies for youth with ASD is the Evidenced-Based Practice Briefs of The National Professional Development Center (NPDC) on ASD. There are Briefs for 24 evidence-based practices that usually include step-by-step directions for implementation, implementation checklist, evidence base and supplemental material.

Two evidence-based practices covered in the NPDC on ASD Briefs, but not in the Autism Internet Modules, which warrant particular attention, are video modeling and peer mediated instruction and intervention. Video modeling is a potentially effective method of teaching complex and multiple vocational skills. Since natural supports are important to success in the workplace, co-worker peer mediated instruction holds promise.

The National Secondary Transition Technical Assistance Center provides a list of strong and moderate evidence-based instruction practices for development of youth with disabilities. (Scroll towards the bottom of the page.) Although the studies that provide the evidence base did not always include youth with ASD, these practices are also effective in instruction of youth with ASD. Skill areas and strategies that are effective to teach them include:

- Employment Skills

- Using Community Based Instruction

- Using Response Prompting

- Job Specific Skills

- Using Computer Assisted Instruction

- Using Constant Time Delay

- Using Self-Management Instruction

- Using a System of Least to Most Prompts

- Completing a Job Application

- Using Mnemonics

Location of Instruction

Depending on the content of instruction and needs of the student, instruction can be provided in the classroom and/or during work experiences that are part of the transition plan (Branham, Collins, Schuster, & Kleinert, 1999). For instance, job search skills like writing a resume or preparing a portfolio, as well as priming for work experiences in the community, are usually appropriate for instruction in the classroom. A job readiness curriculum with emphasis on employability skills taught both in the classroom and in work experiences, which utilizes universal design and instructional strategies effective with students with ASD, may be useful for select students with ASD. However, while other students may rely on textbooks, computer websites, and teacher lectures to learn skills, students with ASD require community-based instruction to learn skills (Virginia Department of Education, 2010).

Youth with ASD, regardless of severity, learn best when skills are taught in real life situations (Wehman, P., Smith, M. D., & Schall, C., 2009) and community-based instruction is an evidence-based practice. The types of relationships, the ways tasks are completed, and the way coworkers interact are unique to each workplace and are governed by a combination of stated and unstated rules. Therefore, both the “hard” skills and “soft” skills for the workplace are best learned in the workplace. That means that all work experience, even job sampling, should have sufficient instructional intensity to develop competencies.

Evaluation

No matter what instructional strategies are used or where it is provided, data needs to be collected to determine progress. Collecting data does not need to be complicated, but it does need to be done on an ongoing basis and consistently reviewed to identify strength on the instruction and to identify areas that need improvement.

What supports are needed by youth and young adults with ASD in the workplace?

Successful transition from secondary school to employment requires strategies that recognize the unique strengths and needs of individuals with ASD. Due to their complex neurological disorder, youth and young adults with ASD are likely to need significant supports regardless of their ability level (Hagner & Cooney, 2005; Hillier, Campbell, et al., 2007; Nuehring & Sitlington, 2003). Without supports, even high-functioning adults generally achieve little more in the workplace than those who are more severely affected by ASD. Young adults with ASD of all ability levels have higher rates of employment and job retention when the necessary supports are identified, evaluated and provided consistently in employment settings. It is vital to recognize that the underlying characteristics of ASD do not go away and that successfully maintaining a job in the community will usually require ongoing supports, not the typical “time limited” ones.

A variety of information and resources for supports related to employment are provided in this toolkit. Because of the importance of supports, Unit 2 focuses exclusively on supports designed to utilize the strengths and accommodate the needs of youth and young adults with ASD. Within this unit, Appendix 3.6C provides a list of potential supports for employment that aligns with Unit 2, while Appendix 3.6A offers links to lists of reasonable and common job accommodations for individual with ASD under Supports for Employment. In addition, Units 3.1 – 3.4 offer important information and resources on supports for communication, social, organization and sensory needs that can arise in any work setting.

Please be aware that any list of supports related to employment is not prescriptive. Since there is a wide range of abilities and needs of students with ASD, the individual supports needed to succeed in employment will vary. Career and vocational assessment that analyzes each work setting and each individual will help identify support needs and the form of those supports for specific work opportunities. Some students may need simple supports, such as a modified break schedule or rearrangement of the workstation. In other instances, more support will be required.

Also, be aware that supports are often needed for more than the actual job. They may be necessary for how to behave in the break room, how to use the bathrooms, how to handle anxiety, how to communicate frustration, or other issues (Rosenshein, 2007). There are many possible ways to support each issue.

The development of supports is worth far more than the time invested in developing them. Often, employers find these accommodations work to support all employees and increase production across the board. However, finding ways to efficiently and cost effectively develop supports is often an issue. Think creatively. In schools, students in a computer skills class or other classes may create many of these as individual or class projects.

Appendix 3.6A

Online and Other Resources

- ASD and Employment

- Guidebooks on Employment for Individuals with ASD

- Assessment for Career Planning

- Instructional Material

- Supports for Employment

- Employment Resources

- Adult Service Organizations in Oregon

- Online Videos

- Online and Other Training

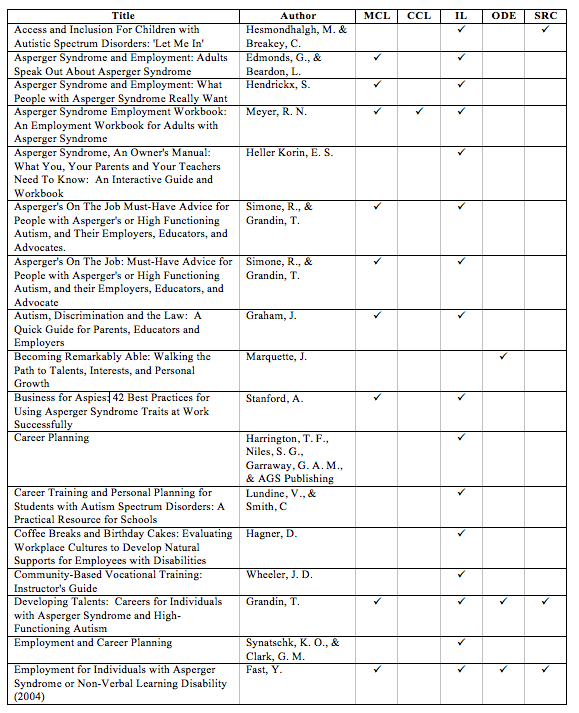

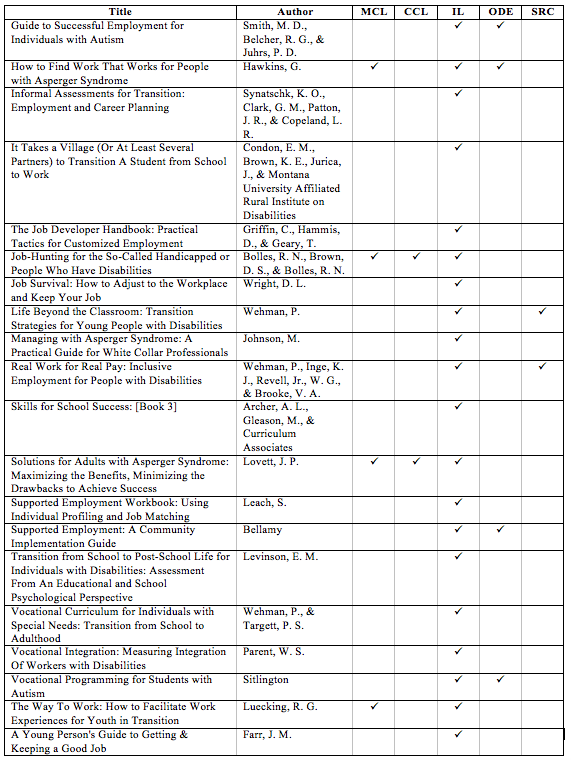

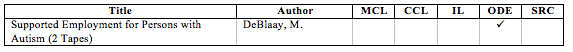

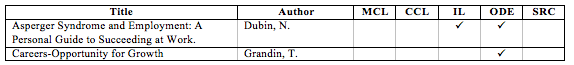

- Practical Books and Audiovisual Material Available on Loan

- Books

- Audio

- Video

The resources listed are available at no cost online. While terminology sometimes differs from Website to Website, the basic concepts are the same. All supports are designed to either, support youth and young adults with ASD, or can be adapted for the individual need of the student. Some websites are listed in several sections because of their relevance to more than one area.

ASD and Employment

Asperger Syndrome, Employment, & Social Security Benefits - K. Collins-Wooley, Asperger's Association of New England. This article is intended to help adults with Asperger’s Syndrome (and the parents, spouses, and mental health professionals who support them) to analyze employability, plan for any reasonable remediation of weaknesses, and identify the characteristics of jobs where adults with AS are most likely to feel comfortable and succeed. For those adults for whom competitive employment is not an option, it outlines how to seek disability benefits.

Autism in the Workplace - Autism Speaks Family Services. This site contains stories of some individuals with ASD who are currently working in various fields captured on video. In addition to the videos, there are summaries of the steps involved in helping these individuals achieve success in a workplace environment.

Autistic Traits: A Plus for Many Careers - About.com. This short article describes the positive nature of some traits of ASD.

Choosing the Right Job for People with Autism or Asperger's Syndrome - T. Grandin, Autism Research Institute. This article offers job tips for those on the spectrum and suggests good and bad jobs.

Employment and Asperger Syndrome - A. Hillier, Asperger's Association of New England. This article provides a discussion about employment and Asperger’s Syndrome, including employment preparation and strategies for the workplace.

For Some With Autism, Jobs to Match Their Talents - Opinionator, Exclusive Online Commentary from the Times. This article describes Specialisterne (“The Specialists”), a Danish company with international offices, that is opening up job opportunities for people with Asperger’s Syndrome and high-functioning autism as software testing and data conversion and management consultants.

Hi Ho, Off to Work We Go - 2002, D. Owens & A. Bixler, Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI). This presentation provides an overview of strategies for employment with individuals with ASD.

On the Job - Autism NOW, The National Autism Resource and Information Center, the Arc of the United States. This site offers information on transition planning for job opportunities, vocational rehabilitation, supported employment and employment research.

Supporting Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Quality Employment Practices - Institute for Community Inclusion. This "Institute Brief" contains a short overview of the types of accommodations that a person with ASD might need in the employment setting in order to be successful. Categories reviewed include: Communication, Sensory, Social, Organization, and support for the employment specialist.

Guidebooks on Employment for Individuals with ASD

Adult Autism & Employment - 2009, S. Standifer, Disability Policy and Studies, School of Health Professionals. This guide is written for vocational professionals, but has applicable information for other stakeholders. It includes a brief description of effective strategies and supports, such as TEACCH, Picture Exchange Communication System, Social Stories, and Comic Strip Conversations. A list of possible accommodations can be found on page 41.

Autism: Reaching for a Brighter Future - Ohio Developmental Disabilities Council. This guide provides practical tips for the transition to work after high school.

Autism Spectrum Disorders and the Transition to Adulthood - Virginia Department of Education. This guidebook has a section on Employment starting on p 47.

Life Journey Through Autism: A Guide for Transition to Adulthood - Organization for Autism Research (OAR), Southwest Autism Research and Resource Center and Danya International, Inc.. This guide provides an overview of the transition-to-adulthood process. Chapter 4, starting on page 25, discusses vocation and employment, including finding a job, available jobs, and ensuring success.

Rehabilitation of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders - 2007, 32nd Institute on Rehabilitation Issues. This manual is for VR counselors and others who are helping adults with ASD navigate work.

Transition to Adulthood: Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders-- Employment - Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI). Section 6 of this guide, starting on p. 44, provides information on evidence based transition practices, implications and strategies for ASD, agency collaboration, and funding related to employment.

Transition Tool Kit - Autism Speaks Family Services. This transition guide provides a section on Employment and Other Options, which describes some options.

Working in the Community: A Guide for Employers of Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorders - This manual was designed to provide a general overview of the characteristics of ASD and general procedures to enhance the volunteer or job experiences of individuals with ASD.

Assessment for Career Planning

Assessment - National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth. This site provides information about appropriate assessment tools that focus on the talents, knowledge, skills, interests, values, and aptitudes of transitioning youth.

The Career Clusters Interest Survey - States’ Career Clusters Initiative (SCCI). This is a career guidance tool. It allows individuals to respond to questions and identify the top three Career Clusters of interest based on their responses. This pencil/paper survey takes about fifteen minutes to complete and can be used in the classroom or for presentations with audiences who have an interest in career exploration. This survey is recommended for students with mild disabilities and a lack motivation.

CAREERLINK Inventory - Monterey Peninsula College. This is a career assessment tool.

Career Planning Begins with Assessment: A Guide for Professionals Serving Youth with Educational and Career Development Chall - National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth. This guide 1) describes the purposes and dynamics of four ways to assess, 2) delineates how to select and use assessment tools, both formal and informal, 3) provides practical information about many commonly used published assessment and testing instruments, 4) describes when and how to seek help or further information about assessments, and 5) reviews legal issues, ethical considerations, and confidentiality as they pertain to assessment and testing.

Employability/Life Skills Assessment - This assesses twenty-four critical employability skill areas for ages 14-21 years identified by Ohio's Employability Skills Project.

Employability/Life Skills Assessment: Parent Form - This parent form for ages 14 – 21 contains 24 critical employability skill areas.

Extended Career and Life Role Assessment System (CLRAS) - Oregon Department of Education. This is the administrative manual for CLRAS, a functional assessment for students with moderate to severe disabilities, that was developed to align to Oregon’s CCG and the Career Related Learning Standards.

O*NET® Interest Profiler™ - This site offers a self-assessment career exploration tool. This tool measures six types of occupational interests: Realistic, Investigative, Artistic, Social, Enterprising, and Conventional. A short form and computerized version is also available. This tool is recommended for students with mild disabilities who are highly motivated and independent learners; 9th grade and older.

QuickBook Of Transition Assessments - Transition Services Liaison Project (TSLP). This guide provides tip for transition planning and transition assessment tools.

Self Assessment: Transferable Skills Survey - Ohio Learning Network. This site provides a survey of transferable skills for students entering the work world

Transition Planning and Application Area: Working - Iowa Transition Assessment. This site provides information on how to do transition assessment for vocational skills.

Transition to Adulthood: Guidelines for Individuals with Autism Spectrum Disorder: Age-Appropriate Transition Assessment - Ohio Center for Autism and Low Incidence (OCALI). Section 2: Age-Appropriate Transition Assessment of this guide provides suggestions for supports for individuals with ASD related to sensory challenges, social/communication challenges, executive function/organization challenges, and ritualistic or repetitive behavior for transition assessment.